The Zettelkasten as a Lattice of Thought Strings

Please welcome Gerrit Scholle, aka gescho from the forums! Gerrit kindly took the time to write up his recent thoughts as a self-contained blog post, with colored pencil drawings and all! Enjoy.

A recent forum post led me to an idea that seemed to be brewing in my subconscious for a little while.

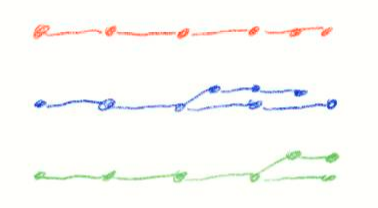

In a Zettelkasten, the individual notes contain (ideally) singular grains of knowledge, or ‘knowledge atoms’ (named after the principle of atomicity). Those are joined with connections of many kind and form strings of thought. Going with the nuclear physics imagery, I like to call those connected notes ‘knowledge molecules’. Graphically, this looks as follows:

The red, blue and green structures in the image above are individual knowledge atoms stringed together into molecules.

Those molecules are the discussion threads about individual topics – when you start at the first connected note, down the rabbit hole you go. Other times, a molecule has a lot of short, stubby branches with definitions and examples in individual notes. In that case, it acts more like a topic category or an index for a topic.

These Knowledge molecules emerge because of the way you assimilate knowledge into your note system. Most often, you will work through one or more sources of knowledge and then input it into the Zettelkasten. Because a source will talk about closely related topics, they form molecules naturally. Where this isn’t the case, they will be attached to already existing molecules, shining new light on a topic, which is why you’re encouraged to look through already existing Zettels when attaching notes. In either case, the following behavior will occur:

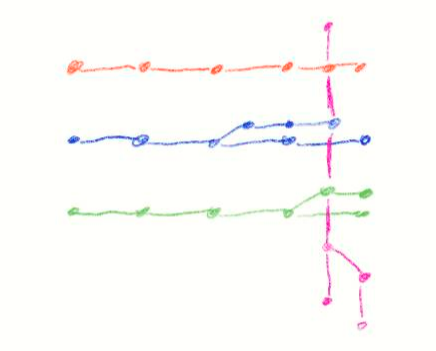

As the number of knowledge molecules increases, there will be more and more connections between individual knowledge molecules. These connections emerge between individual atoms of separate molecules. With enough connections, these interconnections gain a meaning of their own:

A new (pink) molecule appears!

And the same, looking at the emergent knowledge molecule from the its own perspective, with traversable paths to already existing molecules branching out to the side.

They will either form over time, naturally, or are actually separate, deliberate knowledge molecules that are just joined with already existing ones. They can also be manufactured by hand, for example if a source suggests a connection between already existing topics. The reverse can also be true, where a topic has a subset of topics that form their own knowledge molecules.

There are two more ways to connect new information: Sequential notes about a source, and combinatory notes about a topic. These are typical ways of writing notes and can’t connect ideas together. To see why, let’s have a look at each of them:

Theses are sequential notes about two different ideas from two different sources, separated into their own files, be it hand-written or electronic document. Typical for sequential notes are book notes/excerpts and lecture notes.

The notes don’t need to be sequential in the strictest sense – even mind-maps or sketch notes about a book/subject are still individual documents about one source. As you can see, the notes you have written for the sources are independent of each other. You have extracted individual knowledge atoms from the sources, but they remain segregated into the context of the source text. You can’t readily connect similar knowledge atoms of different sources together. For that, you need to use a combinatory note:

These are combinatory notes about one topic from different sources – you pooled all the information about a topic or part-topic into one document. This happens when you do research on a topic – when you think about it, theoretical texts have the same structure of combining different sources into a new document, as well. The Synopticon mentioned in the original forum post also falls into the category of ‘combinatory note’, pooling together many sources about one concept after another. With combinatory notes, you lose the context in which the ideas stood previously – important clues for knowledge work. Also, the researched topic stands on its own. It’s difficult to interconnect combinatory notes about different research topics.

In a Zettelkasten, you separate the knowledge atoms of a would-be sequential note into individual, small documents instead of using monolithic book notes. You can do this while reading, as described in Christian’s article about reading notes. Or you split notes after the fact with already existing sequential book notes.

You would do the same when researching a topic: Writing Zettels about your research, or dividing combinatory research documents into smaller notes. Then you just need to make a note of relevant Zettels in your Zettelkasten – using emergent structures.

This is the resulting network of knowledge atoms in the Zettelkasten which combines sequential notes about a topic into emergent, new structures.

The emergent lattice structures of vertical and horizontal strings of thought are the unique selling proposition of the Zettelkasten Method. The interconnections between the knowledge molecules are the breeding ground for new ideas. This idea formation wouldn’t be possible without free-moving connections and the atomicity of concept which is typical of the Zettelkasten principle.

A few implications for real-life knowledge work with the Zettelkasten that result from this:

- Focus on presenting concepts and ideas in an atomic way. Convert already existing lecture/book/article notes into atomized bits.

- Connect your thoughts – use Folgezettel, structure/hub notes and backlinks thoroughly.

- Look for similar Zettels across topic boundaries. Maybe read a few (semi-)random notes and wait for any associations coming to mind. For me, doing that and then going for a walk helps immensely for ideation.

- Don’t just connect structure/hub notes of similar topics. Go right down to the individual note level in the connection and specify how notes are connected, either in those notes or with a new inter-connection note.

- Traverse those inter-topic connections. Look at their beginning and end. Do you have any associations with that note sequence? Make a Zettel of it, connect them to already existing Zettels, grow the molecule!

- Connections between molecules won’t form if you separate your notes into categories with different Zettelkastens or folders, which is why your Zettelkasten should be monolithic.

- Consider the emergent molecules as strong contenders for being writing material – they should be the most novel ideas in your Zettelkasten.