A Tale of Complexity – Structural Layers in Note Taking

A Zettelkasten is neither a neatly structured filing system for notes easy to access nor a turmoil deep sea generating ideas out of the ununderstandable chaos. There are three layers in my archive which emerged from the years of working with the Zettelkasten Method. I didn’t plan them in advance. It rather was an organic process.

Bottom Layer: Content

The first layer of course consists of content notes. I write, I research, I get ideas. All of that goes into my archive. The full text search and the search for tags are sufficient enough to handle a smaller archive. At this stage it is only natural to stress the importance of tags. You are using them frequently and they serve as important entrances into your archive.

But after a while, you won’t be able to keep up. When I search for tags I get a couple hundred of notes. I have to review them to connect a note to some of them, or get a grasp of what I wrote and thought about a specific topic.

Naturally, a need to organize the archive arises at this point. I can’t remember how many notes I had when I experienced this. I introduced hub-like notes when I had between 500 and 700 notes.1 I gave myself an overview of the most important notes on that topic.

It must have been between 1000 and 1500 notes when this became too much to handle. I needed more structure. With every additional note I continued to lose my grip on the archive. I wasn’t very concerned because Luhmann, the godfather of the Zettelkasten Method, never had a grip in the first place. But I thought: I have a big technical advantage over him. I need a grip.

Then structure notes emerged.

Middle Layer: Structure Notes

My archive became opaque like the sea: You can see a couple inches into the deep but you know there is much more that you can’t access. You can dive deep, but still you just see a couple of inches at any time. Therefore, I thought of it in terms of unexplored territory for which I need mapping methods and such.

I started with structured lists to have tools to get a precise idea quickly how a certain space in my archive is structured. (similar to what Luhmann had with his hub notes, by the way).

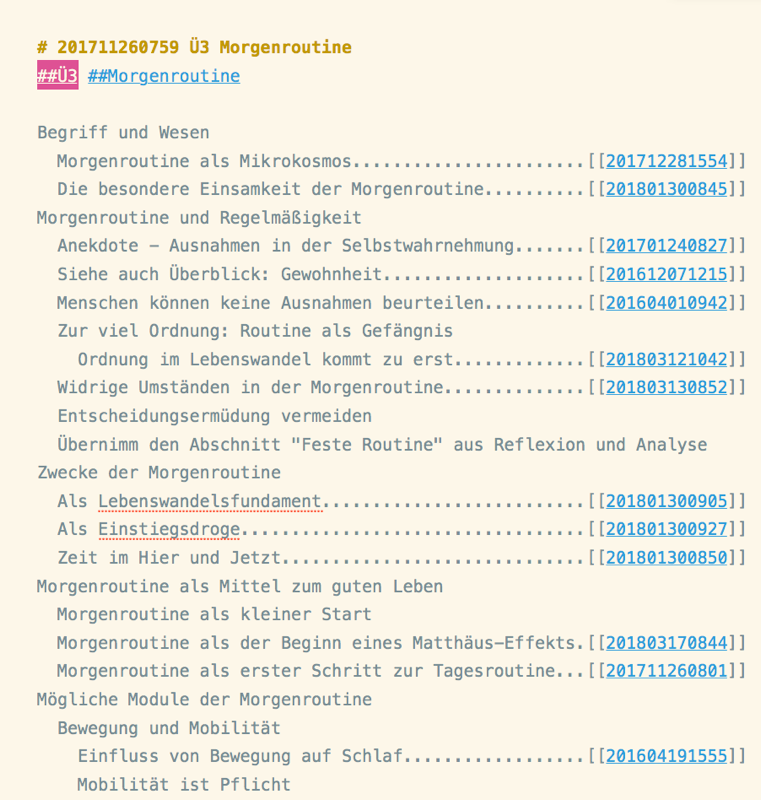

Now, I am at a point where my structure notes embed the structure itself. Take a look at one of my structure notes:

They look much like a table of contents. It’s because they are tables of contents. A table of contents is a structured set of chapters of a book, a set with hierarchy and order. Of course, a book’s page sequence is ordered according to the table of contents for the reader’s convenience. A structure note doesn’t need to adhere to any didactic needs or any needs other than yours.

In the Zettelkasten there are at this point two layers:

- The content. Tiny, tiny bits of content.

- Structure notes. Tables of contents.

Structure notes share a similarity to tags: Both point to sets of notes. Structure notes just add another element. They are sets with added structure. This added structure provides a better overview and adds to the utility of the archive.

Top Layer: Main Structure Notes and Double Hashes

After a while, I did not only have structure notes that structure content notes, I also had structure notes that mainly structured sets of structure notes. They became my top level structure notes because they began to float on the top of my archive, so to say.

My structure note on human movement is a perfect example of it. First, I wrote a lot about training. The training structure note linked to strength training, endurance training, sprint training, strongman training, mobility training, and more. But after a while a couple of topics didn’t fit into this space. What about physical work like wood chopping or the whole space of non-movement (like chronic sitting)? The topic broadened and I found a new umbrella: Human Movement. This structure note just keeps on floating on top. It is like the tip of an iceberg. No matter how much water freezes and is added to its body, the top stays on top.

Another type of top-level structure notes are the one I design in this manner right away. I worked a lot on the topic of self-worth from various perspectives (even from the perspective of cardinal sins; the perspective is broad!). The structure note is tagged with a special tag: ##self-worth. If I search for #self-worth (note the single hash!) I get all the notes that deal with this concept but with a double hash I go directly where the money is in my archive: The top-level structure note.

The difference between these two kinds of top level structure notes is in how they turn out to become top level: Human Development emerges because of the structural changes in my archive, while the one with ##self-worth is marked as a top-level structure note because I designed it to be a top-level note right away. (I mark the human development note with a double-hash, too).

Why Bother Telling This Story

There are emergent structures that underly every self-organizing body of knowledge. Software that helps you deal with these structures needs to fulfill a couple of criteria for its ability to handle complex structures. One criterion is: Does the software provide access to those different structural layers? If it doesn’t offer the means to deal with those structures, it won’t help you in your work once your archive becomes more complex.

A sign of not dealing with structural layers are project folders, and folders in general. If you can’t cope with potentially infinite complexity you have to compensate. One way of compensation is lowering the demands on the system. If a system encapsulates single projects or topics, chances are that it can’t cope with complexity. This is okay if you want to just work on one project. But if you want to use a system as an aid to writing and as a thinking tool you should opt for a system that is powerful enough for a lifetime of

thoughts. So, watch out for folders and projects. They are the means for dealing with encapsulating and limiting complexity. In addition, they hinder the most productive way of knowledge production: the interdisciplinary part.

Even more important is that all this isn’t about the software. It is about the system you set up. Some software nudges you, sometimes even pushes you, towards system design decisions. Take Wikis as an example. Most of them have two different modes:

- The reading mode.

- The editing mode.

The reading mode is the default. But most of the time you should create, edit and re-edit the content. This default, this separation of reading and editing, is a small but significant barrier on producing content. You will behave differently. This is one reason I don’t like wikis for knowledge work. They are clumsy and work better for different purposes.

The issue of the different layers is similar. If you chose software that doesn’t deal with those layers in a sophisticated way, you will not reap the benefits in the long term. Your archive will note work as a whole. I think that this is one of the reasons why many retreat to project-centered solutions, curating one set of notes for each book, for example. The problems that come with big and organic (= dynamic and living) systems is avoided. But so is the opportunity to create something that is greater than you.

-

Luhmann used this concept himself. ↩