Introducing the Antinet Zettelkasten

Today, we’re happy to introduce you to Scott P. Scheper via this introduction to his fully, 100% analog and paper-based approach to Zettelkasten! Make sure to also check out his videos for a live demo at the end. Enjoy!

Before we begin, please note that this piece assumes intermediate familiarity with Zettelkasten and its original creator, the social scientist Niklas Luhmann (1927–1998). It also is more conceptual in nature rather than a practical guide for how to build your own Antinet Zettelkasten.1

My goal is twofold: (1) I hope to motivate those who prefer paper-based thinking systems, and (2) I hope to present an alternative perspective for those who use digital Zettelkasten systems. I hope my perspective will add one or two valuable insights you can add to your Zettelkasten workflow (even a digital one).

Let’s get started.

In brief, an Antinet Zettelkasten possesses four principles. These four principles delineate what an Antinet Zettelkasten is and what it is not. Let’s explore these four principles now.

The Four Principles of an Antinet Zettelkasten

The four principles Niklas Luhmann used to build his notebox system are:

- Analog

- Numeric-alpha

- Tree

- Index

The first letters of those four principles (A, N, T, I) are what comprise an Antinet. An Antinet Zettelkasten is a network of these four principles.

Let’s dive into each of these four principles now.

Principle #1: Analog

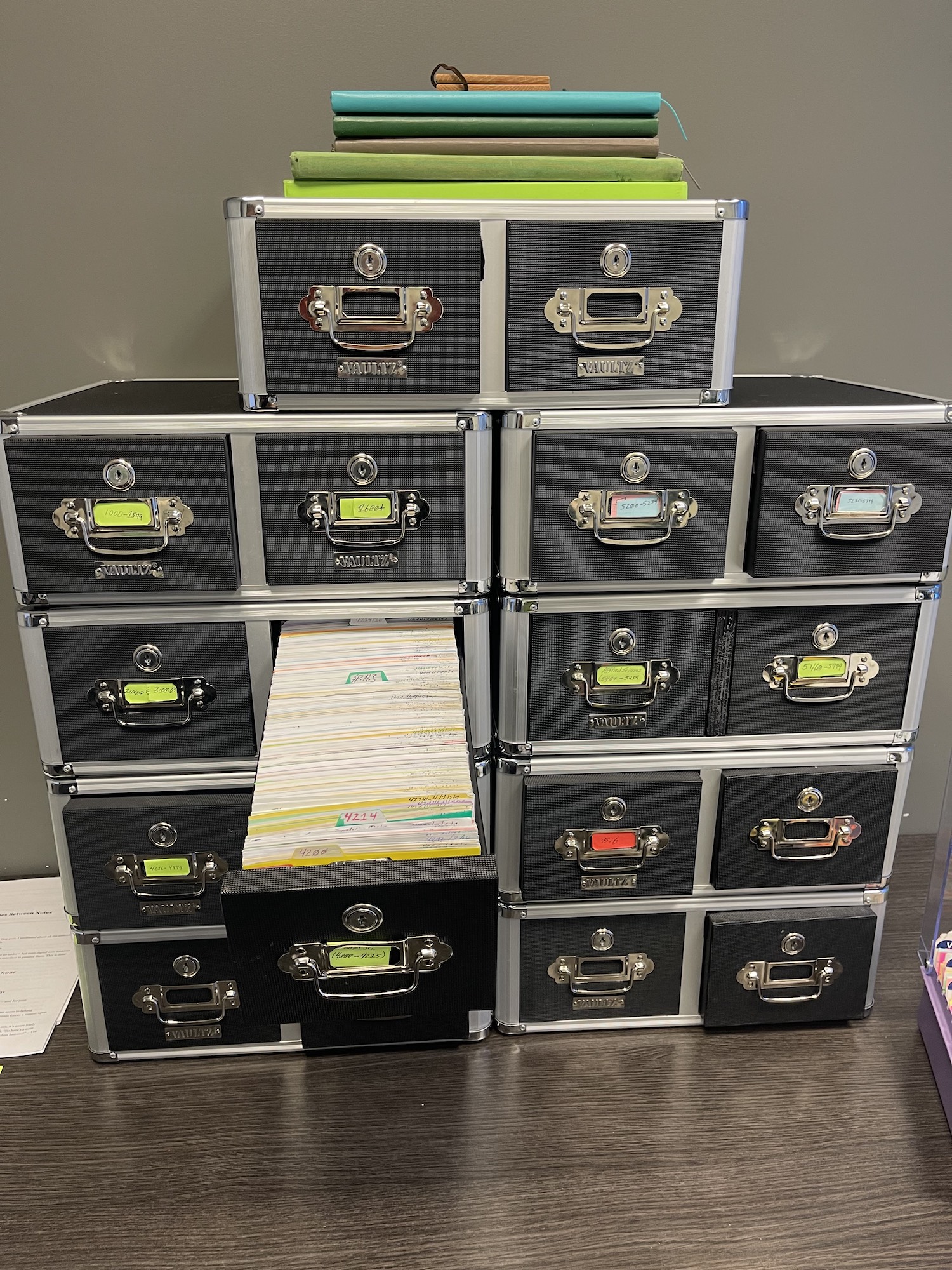

The first principle is what Luhmann calls a technical requirement for a Zettelkasten. He refers to its analog nature as an externality, meaning it’s an indirect benefit to the other core principles of the Zettelkasten: “Wooden boxes, which have drawers that can be pulled open, and pieces of paper.”2

I hold that physical materials unlock some of the most powerful results that drive one’s experience using a Zettelkasten.

Luhmann did not specify analog as a requirement over digital. The reason why is simple. Digital tools were not an option when he started building his Zettelkasten. I believe that if Niklas Luhmann were alive today, he would continue using physical materials to develop his thinking. In future writings, I will share why Luhmann would continue using an analog Zettelkasten if he were alive today.

Principle #2: Numeric-alpha

Perhaps the most crucial principle in the Antinet Zettelkasten is the Numeric-alpha notecard address. What is meant by Numeric-alpha is simply this: addresses which start with a number and are combined with alphabetical characters. For instance, a notecard with an address in the top corner like: 3306/27A. This enables what Luhmann phrased as “the possibility of linking.”3 It’s the very thing that allows the system to become self-referential and a cybernetic network, as Luhmann thought of it.4 The system is self-referential in that it can refer to its individual parts (each individual thought). One way to think of this is to think about yourself. You are a system. You have distinct pieces of yourself (like your left hand). Your left hand has its own label (i.e., ‘left hand’). This allows one to reference their individual parts. The same becomes true with the Antinet, thanks to Numeric-alpha addresses.

When people first see a notecard address like 3306/2A/12, they think of it as a hierarchical system. Yet it’s not. It’s merely the location of where the leaf lives on a branch or stem on your tree of knowledge. Think of it more like a geographic coordinate system, like a latitude and longitude scheme (for instance, -77.0364,38.8951). The slashes do not connote that of a hierarchy; the address ‘3306/2A/12’ could simply be represented as 3306.2A.12, and that would be just fine. It’s a matter of personal preference.

The Numeric-alpha address stands as a vital principle in Luhmann’s system. The Numeric-alpha address not only enables linking but also enables the self-referential composition of the Zettelkasten. The Numeric-alpha addresses never change; however, due to the infinite internal branching of the system, its position shifts over time.

The Antinet’s permanent-address scheme, with its shifting nature, gives the system a unique personality. The Antinet’s unique personality stands as one of the most integral aspects of the system.

A key component that enables insightful communication with a human being is the human’s personality–the person’s unique way of communicating with you based on their unique perspectives and interpretations. The Numeric-alpha addresses provide the Zettelkasten with a unique personality. Over time, unique structures form due to Numeric-alpha addresses. This is important because it allows one to communicate with the Antinet, transforming it into a communication experience with a second mind, a doppelgänger, or a ghost in a box, as Luhmann called it.5 This is the entity Luhmann referred to when he titled his paper, Communicating with Noteboxes.

Numeric-alpha addresses make all of this possible.

Principle #3: Tree

The third principle is based on something Luhmann refers to as “the possibility of arbitrary internal branching.”6

How can one devise a system built on that which best models reality? Reality is chaos, yet it also emerges from ordered and simplistic rules (think the laws of thermodynamics). Reality emerges from simplistic laws (for instance, the atomic theory–that all matter is composed of particles called atoms). Reality is chaos built out of simple laws of order. These simple laws and units of order bind the system together, allowing one to navigate complexity. It was with both chaos and order in mind that Luhmann crafted his notebox system.7

Within the current popularity of communities around Personal Knowledge Management (“PKM”), it’s become a popular idea to embrace so-called dynamic systems. Ones that are fluid and are built on things like wikilinks and tags. It’s become popular advice to ditch systems that use folders and directory structures.8 This notion, however, is a rather new idea. Luhmann’s Zettelkasten was not dynamic, nor was it fluid. It looks almost as if it’s built entirely of folders (in the digital computer directory sense).

I argue that you should not strive for dynamic, fluid systems–ones that constantly can update themselves with find-and-replace text features. Such a structure would be lacking in rough, unique conventions. It would lack a unique personality or an “alter ego,” which is what Luhmann’s system aimed to create.9 One of Luhmann’s goals centered on replacing the need for an “expensive” research assistant.10 The way he achieved this was by architecting one with its own unique personality: his Zettelkasten.

Simply stated, Luhmann’s Zettelkasten structure was not dynamic or fluid in nature. Yet, it was not rigid, either. Examples of a rigid structure are classification systems like the Dewey Decimal Classification System or Paul Otlet’s massive notecard world museum known as, The Mundaneum. These types of systems are helpful for interpersonal knowledge systems; however, they’re not illustrative of what Niklas Luhmann’s system was: an intrapersonal communication system. Luhmann’s notebox system was not logically and neatly organized to allow for the convenience of the public to access. Nor was it meant to be. It seemed chaotic to those who perused its contents other than its creator, Niklas Luhmann. One researcher who studied Luhmann’s system in person says, “at first glance, Luhmann’s organization of his collection appears to lack any clear order; it even seems chaotic. However, this was a deliberate choice.”11 Luhmann’s Zettelkasten was not a structure that could be characterized as one of order. Indeed, it seems closer to that of chaos than order.

If Luhmann’s notebox system was not dynamic and fluid and not one of pure order, either, how can one think of Luhmann’s notebox system? In my experience using an Antinet Zettelkasten, I find it to be more organic in nature. Like nature, it has simple laws and fundamental rules by which it operates (like the laws of thermodynamics in physics); yet, it’s also subject to arbitrary decisions. We know this because in describing it, Luhmann uses the word arbitrary to describe its arbitrary internal branching. We can infer that arbitrary, means something that was decided by Luhmann outside of some external and strict criteria (i.e., strict schemes like the Dewey Decimal Classification).12 This arbitrary, random structure contributes to one of its most distinctive aspects of the system–the aspect of surprises. Because of its unique structure, the Antinet is noted as “a surprise generator,” and a system that develops “a creativity of its own.”13

Let’s jump back to the question: How can one think of Luhmann’s notebox system? It’s quite simple, and I’ll share with you precisely how you should think of the Zettelkasten in just a moment. Until then, it’s essential to close the loop on the characteristic which describes it.

One of the knowledge scientists who studied Luhmann’s Zettelkasten closest is Johannes Schmidt, who works at Bielefeld University in Germany. Schmidt is currently the scientific coordinator of a project to digitize Luhmann’s notebox and publish its contents online for all to explore.14

According to Schmidt, Niklas Luhmann’s notebox system is “a rough structure.”15 It’s organized “by subject areas, which is reflected in the first number assigned to the card.”16 A rough structure comprises both “order and disorder,” as Luhmann put it.17

I propose that one ought not to think of the Zettelkasten as a dynamic or fluid structure. Nor should one think of the Zettelkasten as a system of complete order. As Johannes Schmidt observed, I hold that it’s most precise to think of it as a rough structure. Yet, knowing this gets us only so far. Knowing the abstract traits of a system is nice, yes, but not really that useful in practice. For this reason, I’ll share with you what I’ve found to be the best illustration of what type of structure a Zettelkasten is.

Think of a Zettelkasten as a tree. A real tree. What does a real tree contain? It contains a trunk, branches, stems, leaves, and vines (depending on the tree). Think of each individual leaf as a notecard. With a Zettelkasten, you’ll be building a tree of knowledge. One that has different branches, different stems of thought, and even vines that link to other branches. This allows one to explore and swing between branches, stems, and leaves.

The importance of the Zettelkasten’s tree-like structure should not be overlooked. Long-term memory works in a way that closely models tree-like structures.18 The same thing goes for the human brain, neurons, and neural networks. Some of the most beautiful tree-like images are the networks of the human brain.19

This helps create a concept I like to call the second mind. The second mind is something different than the PKM term of second brain. The structure of the Zettelkasten is critical because it makes possible the emergence of a second mind. It’s not about storing information and creating bubbles that link concepts together; instead, it’s about exploration, as one knowledge scientist put it.20 It’s about exploration from one card to the next, and jumping to cards linked to remote branches. The tree structure of the Zettelkasten enables meaningful exploration. One knowledge scientist goes on to say, “secondary memories themselves have an inner order that allows for exploration.”21 Such things are enhanced by the tree structure of the Zettelkasten.

Principle #4: Index

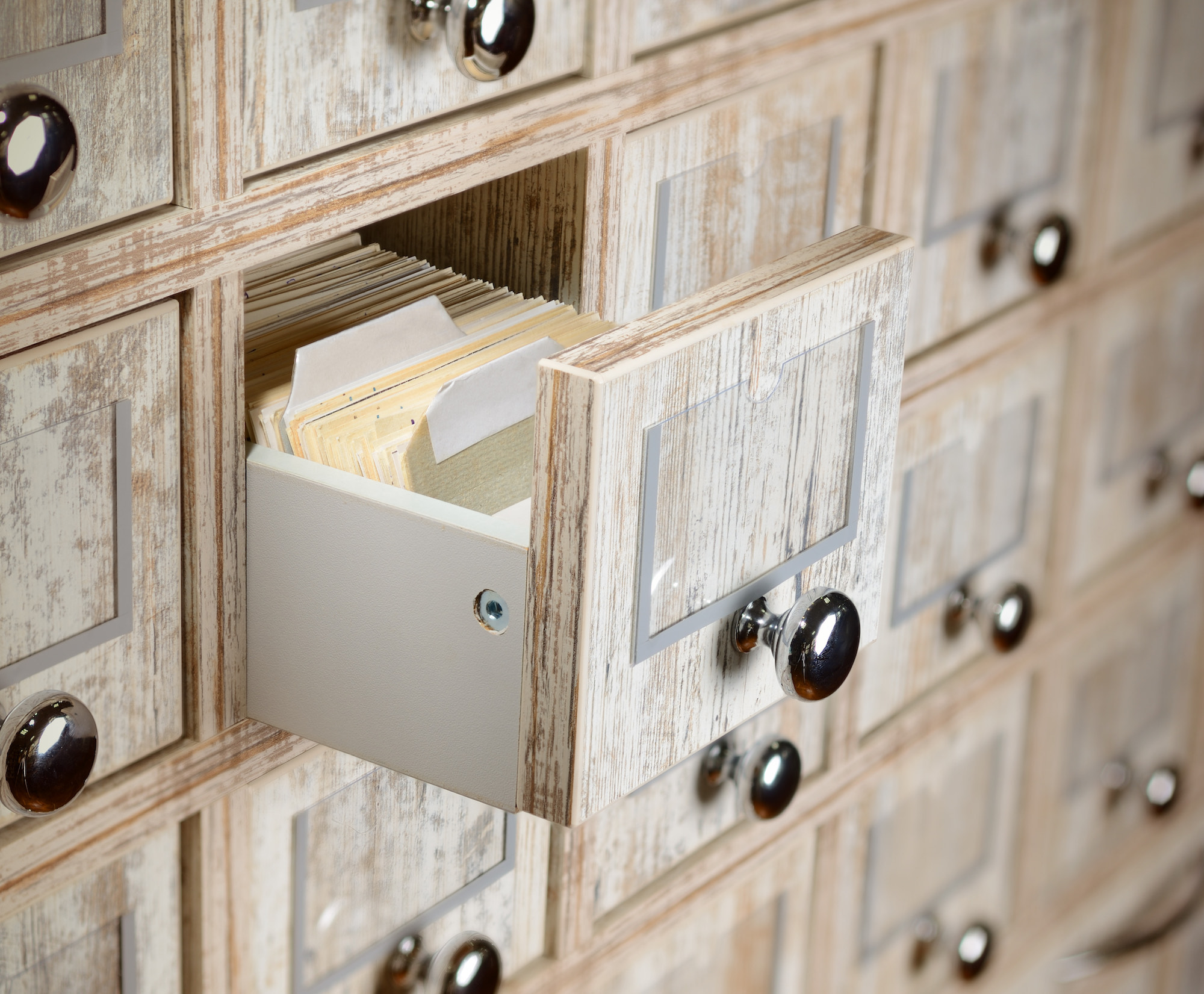

The last principle in Luhmann’s notebox system is the index. Luhmann calls this concept a “Register.”22 I prefer index, but you’re welcome to use whatever terminology you like best. You can think of the index as a map for exploring your own tree of knowledge.

Say you’re traveling, staying in a new location, and suddenly you realize you haven’t eaten all day. You’re starving. You think to yourself, I’m really craving In-N-Out Burger right now. You recall seeing an In-N-Out Burger the previous day, but since you’re traveling, you’re not sure how to get there. You then pull out your phone and open up the maps app. What do you do next? Do you type in ‘32.7794303,-117.242262’? Or do you type in the human-memorable name ‘In-N-Out Burger’? Chances are you opt for the human-memorable name. This is precisely how to think of the index for you Zettelkasten. The index is a key-value associative array. The keyterm is the human-readable name, and the value is the location of the leaf on a tree in your Zettelkasten. For instance, here’s an example taken directly from my own Zettelkasten: ‘Truth’: ‘5455/1’. This should look familiar if you’re familiar with data structures like JSON, Python dictionaries, or YAML arrays. You can get pretty advanced with your index and create nested items. However, I won’t cover such now.

The bottom line is this: think of the index as your own map that enables you to swing onto a specific leaf, on a certain branch of a particular tree. From there, you can then continue exploring by reviewing the nearby stems of thoughts and the individual cards, which, themselves, contain remote links. These remote links enable you to swing around to other leaves on other branches of your tree of knowledge.

Introducing: “The Antinet”

Now that you know what the four principles are that Luhmann used to build his Zettelkasten, let’s summarize them briefly here.

The four principles Luhmann used to build his notebox system are:

- Analog

- Numeric-alpha

- Tree

- Index

The first letters of those four principles (A, N, T, I) are what comprise Antinet. It’s also the four specific principles comprising a Luhmannian Zettelkasten.

When first coming across the term Antinet, many people may mistake it for being anti-digital, or anti-technology. However, if you spend some time reading or watching what I actually say, I’m actually not as anti-digital as one would think. If one elects to stick with digital as their medium of choice for an Antinet, just drop the analog principle and stick with the rest (Nitnet). There are good reasons why you’d want to still ascribe to the other principles. One reason centers around stamping cues onto your mind (by way of using a manual index). This helps you retrieve thoughts instantly. It exercises your brain’s neuro-associative recall muscle. This happens by way of using the index (but also the Analog component helps significantly via neuro-imprinting).

To be clear, I am anti-digital when it comes to a thinking development system such as the Antinet; but within reason. I understand that some people may operate and think better with digital tools. That’s fine. I believe a digital Zettelkasten is a compromised version; yet it seems to be a useful tool for others. However, after you read the research backing an analog thinking development system, I hope you’ll at least give it your best shot before reverting to the digital version.

Before we move on, there’s one last thing you should know. It pertains to the net in Antinet.

The Net in Antinet

The net in Antinet refers to network. To Luhmann, the system he built was a network, a cybernetic network.23 The Antinet, according to Luhmann, was self-referential in nature. It was self-referential because of its ability to reference itself via the numeric-alpha addresses.

This is all I’ll say about the network component of the Antinet for now.

What an Antinet Really Is

Now that you know the four principles of Luhmann’s notebox, you’re closer to understanding it. But there’s only one problem: you now know what an Antinet is comprised of, but you still have no idea what an Antinet really is. The reason why centers around the four principles merely describing the parts of Luhmann’s system. They describe its fundamental raw organs. You can’t understand what a human being is just by learning it’s made up of seventy-eight organs. The individual parts do not represent the whole that it creates. Like a human being, the four parts of an Antinet combine to create a whole more significant than the sum of its parts.

When the four principles are combined into a system, the Antinet becomes a thinking tool, a communication partner, and a second mind. They combine to create many other novel phenomena, such as insightful surprises by way of ordered randomness. The Antinet becomes a system where thought is developed–both in the short-term, by way of thinking on paper with pen; as well as in the long-term, by its branched architecture that stamps things in time that are most useful later on (this includes mistakes in your own thinking that are stamped in time, which prove valuable later on). Also stamped in time is that of your own mind and its own context, with its own links that it thinks of at the time of writing and developing thought. In brief, there’s temporal context that is stamped and installed into your Antinet. This context, and your inner voice, evolve into a second mind enabling you to communicate with your Antinet (and in Luhmann’s phraseology, to ask it questions). It is the combination of all four of its principles that transform the Antinet from a mere notebox into a second mind–a whole greater than the sum of its parts.24

Magic takes place when the four principles interact in the Antinet:

- The neuro-imprinting on the mind via its analog medium of writing by hand.

- The “(selective) relations” between notes are enabled via the numeric-alpha addresses.25

- The “special filing technique,” with its infinite internal branching via the tree structure.26

- The index enables you to neuro-imprint ideas and cues in human-memorable language.

All of these four things interact and create unexpected effects. When you experience new links in the Antinet you unleash a phenomenon in human memory called reverberation. This refers to a “just-experienced association” setting off a ticking clock for a short period of time. Before the clock winds down, the association is easier to recall.27 The Antinet’s structure enables you to retain more knowledge and connections than you ever thought possible. You’ll begin to notice yourself reading differently. Certain keyterms you’ve stamped onto your mind by way of the deliberate act of writing them onto your index will start to arise while reading; all you have to do oftentimes is simply write down the keyterm in the book’s margin. Or, if you do not wish to write in a book’s margins, you can write the keyterm down on a notecard you keep with you while reading, which is what Luhmann did. This notecard acts as a staging area for your thoughts before you transform them into full reflections on individual cards.

As it relates to the four principles, this structure, as Johannes Schmidt observes, demonstrates how quickly the Antinet sets you on a path away from what one would deem ordered (and taxonomically sound).28 Although seemingly nonsensical, to the creator–that is, to you–the Antinet becomes perfectly natural to understand. One is lead away from the original topic and to a variety of other subjects that he or she would not have initially associated with one another.29 All of these incommunicable experiences are formed by the structure of the Antinet’s four principles.

The whole of an Antinet is incommunicable–meaning, you’ll need to understand it yourself by experiencing it yourself.

Wrapping Things Up

An Antinet, defined, comprises four principles (Analog, Numeric-alpha, Tree, Index) which form a thinking system network. This system, in turn, transforms itself into a second mind.

It may not seem like much from this definition, but there’s a lot to unpack here. I’ve provided you with a brief overview of the four principles of an Antinet. Yet, I’ve not adequately covered the concepts of an Antinet as a thinking system, nor have I covered the second mind in detail.

Such concepts, and others, will be covered in the book I’m working on related to the Antinet. I’ve spent much of the past year researching and writing the book.

If you want to learn more about the Antinet, and if you want a free copy of the book when it’s released, please head over to my website and sign up for my newsletter: https://scottscheper.com

Warm regards,

Scott P. Scheper

Sascha’s Comment: When I saw that Scott actually had built a sizable Zettelkasten, I was eager to ask him to present his perspective on the matter on this blog. Though I disagree with him on a number of points, I think his perspective is very valuable for the overall exploration of how to develop a thinking machine.

There is one thing I fully agree with: There is a very beneficial effect of writing in longhand.

I, myself, will definitely check out his book when it is published.

Christian’s Comment: I second Sascha’s impressions – there’s so much talk about paper-based note-taking systems, but nobody seems to stick to it long enough to truly write from their heart and experience. Scott’s personal Antinet looks like a sizable accomplishment on its own! (More videos on his YouTube channel)

-

For a more practical guide on building your own Antinet, try these two sources: (1) https://scottscheper.com/letter/1/, (2) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kj9zwGex-y0. ↩

-

“Communicating with Slip Boxes by Niklas Luhmann,” accessed May 4, 2021, https://luhmann.surge.sh/communicating-with-slip-boxes. ↩

-

“Communicating with Slip Boxes by Niklas Luhmann,” accessed May 4, 2021, https://luhmann.surge.sh/communicating-with-slip-boxes. ↩

-

“ZK II: Note 9/8 - Niklas Luhmann Archive.” Accessed January 10, 2022. https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/Zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8_V. ↩

-

“ZK II: Note 9 / 8.3 - Niklas Luhmann Archive,” accessed January 11, 2022, https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/Zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8-3_V. ↩

-

“Communicating with Slip Boxes by Niklas Luhmann,” accessed May 4, 2021, https://luhmann.surge.sh/communicating-with-slip-boxes. ↩

-

“Communicating with Slip Boxes by Niklas Luhmann,” accessed May 4, 2021, https://luhmann.surge.sh/communicating-with-slip-boxes. “This parallel should not be exaggerated; but you will not be mistaken in the assumption that in society and especially in the realm of scientific research order results only from a combination of disorder and order.” ↩

-

“1c.3 Using Folders - LYT Curriculum / Unit 1 - PKM & Idea Emergence,” Linking Your Thinking, accessed October 25, 2021, https://forum.linkingyourthinking.com/t/1c-3-using-folders/142/2. “Folders are rigid and exclusionary by their nature. Whatever is in a folder lives separated from the main collection. It’s a rigid hierarchy that imposes order.” ↩

-

“Communicating with Slip Boxes by Niklas Luhmann,” accessed May 4, 2021, https://luhmann.surge.sh/communicating-with-slip-boxes. We find evidence of Luhmann gearing his Zettelkasten to emerge as a communication partner and develop its own personality from Luhmann stating, “As a result of extensive work with this technique a kind of secondary memory will arise, an alter ego with who we can constantly communicate.” We also see Luhmann emphasizing the idea that the Antinet takes on its own life–its own type of person from Luhmann stating, “it gets its own life, independent of its author.” ↩

-

“ZK II: Sheet 9/8.1 - Niklas Luhmann Archive,” accessed February 6, 2022, https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8-1_V; “ZK II: Zettel 9/8,2 - Niklas Luhmann-Archiv,” accessed February 6, 2022, https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8-2_V. In these notes Luhmann created in preparation for his paper on communicating with his Zettelkasten, we Luhmann deliberating with himself on how to create a personality–meaning, a true communication partner in the form of a person. The reason Luhmann desired to do this, opposed with hiring a “junior partner,” or research assistant centers on such being too expensive. ↩

-

Johannes Schmidt, “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine,” Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe 53 (2016), https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2942475, 290. ↩

-

Angus Stevenson and Christine A. Lindberg, eds., New Oxford American Dictionary 3rd Edition, 3rd edition (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). ↩

-

Johannes Schmidt, “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine,” Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe 53 (2016), https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2942475, 290. ↩

-

“PEVZ: Johannes Schmidt - Contact (Bielefeld University),” accessed January 11, 2022, https://ekvv.uni-bielefeld.de/pers_publ/publ/PersonDetail.jsp?personIde3450. ↩

-

Johannes Schmidt, “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine,” Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe 53 (2016), https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2942475, 295. ↩

-

Johannes Schmidt, “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine,” Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe 53 (2016), https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2942475, 295. ↩

-

“Communicating with Slip Boxes by Niklas Luhmann,” accessed May 4, 2021, https://luhmann.surge.sh/communicating-with-slip-boxes. ↩

-

Xiaodan Zhu, Parinaz Sobhani, and Hongyu Guo, “Long Short-Term Memory Over Tree Structures,” ArXiv:1503.04881 [Cs], March 16, 2015, http://arxiv.org/abs/1503.04881. ↩

-

For beautiful images, and exploration on this subject, see: Giorgio A. Ascoli, Trees of the Brain, Roots of the Mind (Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2015). “If each nerve cell enlarged a thousandfold looks like a tree, then a small region of the nervous system at the same magnified scale resembles a gigantic, fantastic forest.” ↩

-

Alberto Cevolini, ed., Forgetting Machines: Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe, Library of the Written Word, volume 53 (Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2016), 16. ↩

-

Alberto Cevolini, ed., Forgetting Machines: Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe, Library of the Written Word, volume 53 (Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2016), 16. ↩

-

“Communicating with Slip Boxes by Niklas Luhmann,” accessed May 4, 2021, https://luhmann.surge.sh/communicating-with-slip-boxes. ↩

-

“ZK II: Note 9/8 - Niklas Luhmann Archive.” Accessed January 10, 2022. https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/Zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8_V. ↩

-

It’s become a marketing idea of late to refer to a system that stores information as a second brain; yet, that’s not really what you want, nor is that even a good term for what you’re developing with an Antinet. What you’re building is a second mind. In the scholarly field, this idea is often referred to as an extended mind. ↩

-

Johannes Schmidt, “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine,” Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe 53 (2016), https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2942475, 309. ↩

-

Johannes Schmidt, “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine,” Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe 53 (2016), https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2942475, 309. ↩

-

Michael Jacob Kahana, Foundations of Human Memory. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 9. ↩

-

Johannes Schmidt, “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine,” Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe 53 (2016), https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2942475, 309. ↩

-

Johannes Schmidt, “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine,” Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe 53 (2016), https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2942475, 309. ↩