Using Cartography as a Metaphor for Investigating the Great Folgezettel Debate

Today, we’ve got a post by Austin Ha (@iamaustinha on the forum and on Twitter) that tackles the Folgezettel–vs–links-only debate from a different perspective – cartography! Austin went really far in preparing example archives to illustrate everything (download link at the bottom) so thank a lot for all this work!

As a novice Zettler introduced to the method via the Cortex podcast, I’ve been taking the last year or so to build up the foundations of a useful archive. I’ve come to an inflection point in the management of my archive, as I’ve done a lot of collecting and not a lot of assimilating, linking, etc. Of course, at this new stage, it’s only natural that I’ve stumbled upon the Great Folgezettel Debate. After going on a deep dive in the forums for the past week, I’ve come to the point where I’d like to start weighing the tradeoffs between the two most prevalent organizational techniques I see discussed here: Folgezettel and Structure Notes.

While I think I have a feel for where I’ll land at the end of this, I want to float my ideas in the forums first to see how they land.

Topography of a Zettelkasten

I’m a big fan of laying some foundations before discussing anything, so I’d like to begin with a deeper investigation of a metaphor I’ve seen pop up when Folgezettel are discussed: topography.

I first saw the discussion of “topography” in this post, but have seen both implicit and explicit discussions about the idea of the topography of a Zettelkasten all throughout the forums (see here for example). Instinctually, I love this term in the context of Zettelkasten, and at the beginning of this post I want to call for help crystallizing a definition for what we mean when we talk about topography. My working definition:

Topography of a Zettelkasten := The arrangement of connections that exist in an archive.

I would expand on this to say that the Topography of a Zettelkasten “mirrors” the Topography of all possible connections within a Zettelkasten. In other words, the connections that are in our Zettelkasten are a subset/selection of all the possible connections that could exist (which seems trivial to state). Again, our practical, real Zettelkasten is an image of this “Maximal” slip box with all possible connections, but not an exact image – in fact, an exact image would not be useful to us…knowing that every note can be connected to every other note for some reason would not be useful in practicality, but I digress. So, for another working definition:

Topography of Knowledge in a Zettelkasten := The arrangement of connections that exist in a “Maximal” archive.

Cartography as a Metaphor

Before moving on, it’s worthwhile to note that the language of “mapping” out the knowledge in a Zettelkasten is already common (see here and here, for example). Personally, I’ve come to find the idea of mapping out knowledge to be more apt than I’d initially realized.

To play with the metaphor a bit, if there is a Topography of Knowledge in our Zettelkasten, then it makes sense that we should explore that Topography and selectively map out the connections the Topography contains for our use. In this case, our existing Zettelkasten is the map that we are constructing of the knowledge in the Maximal Zettelkasten.

If we’re making maps, that makes us cartographers. As such, I propose we can use cartographical language when discussing our ZK:

Here are the “fundamental objectives of traditional cartography” (via Wikipedia):

- Map Editing: “Select traits of the object to be mapped.”

- Generalization: “Eliminate characteristics of the mapped object that are not relevant to the map’s purpose” (see above) and “reduce the complexity of the characteristics that will be mapped.”

- Map Design: “Orchestrate the elements of the map to best convey its message.”

- Map Projection: “Represent the terrain of the mapped object on flat media.”

Here’s how they manifest in a ZK:

- ZK “map editing”: We must select the traits we are interested in mapping. Of course, as @sfast notes, anything can be related to anything else (i.e. being “too creative” when making connections may not be useful), but it is our selection of interesting traits that makes our Zettelkasten useful to us based on the “comparative schema” we bring to the slip-box at any given time, as Luhmann writes about. I suggest our filter is simply “features/connections we find interesting,” which (again) seems trivial to state.

- ZK “generalization”: We act upon the traits we’ve chosen in the “map editing” phase and only comparatively “file” (whether it be using Folgezettel, Structure Zettel, or something else) our notes selectively, placing them in contexts that are interesting or useful for us to continue lines of thought in our ZK (Eva Thomas (@ethomasv) covers this well here). We must also work to reduce the complexity of the things we do map (and we do this by choosing key features to focus on like topics, projects, curiosity, etc.).

These cartographical goals for our Zettelkasten cover the first two fundamental objectives of traditional cartography; they make up the foundation of ZK exploration: we comparatively file our notes, inherently using a comparative schema to place the note in one or more relevant contexts across the span of our archive. We are discovering connections as we traverse the notes in our archive.

We’ll assume here that we don’t make connections that aren’t useful to us (on an infinite timescale we could always make meaning of all the relationships established in our ZK), but the important takeaway is that editing and generalization are covered by the simple act of placing a note in the archive and settling it in a context, possibly via Folgezettel or Structure Zettel – but which method should we choose?

For the remaining two cartographical goals:

- ZK “map design”: This, I propose, is the heart of the great Folgezettel debate. The question is: how do we orchestrate all of the elements above (the selected connections to be mapped) in a way that allows the Zettelkasten to serve as a “thought partner?” So far, the most popular methods of achieving this have been through direct links and either Folgezettel (or Folgezettel-like structures) or Structure Notes.

- ZK “map projection”: Deciding how to project our Topography onto a 2D space is what I see as a missing key to the Folgezettel debate. The similarities strike me here: we are literally projecting the complex Topography of our ZK into a 2D space: the text editor that’s on our screen. I think this similarity has been most vigorously alluded to by those who have been the largest advocates for Folgezettel, such as @pseudoevagrius and @argonsnorts , but I don’t know of anywhere that has explicitly stated that the community should discuss how we see and traverse our knowledge Topography. (Maybe @Sociopoetic , our resident cartographer, has thoughts?)

A small note: while many of these goals seem to intermingle in their means and ends, I do think it’s especially important to note that it seems like map projection is a part of map design.

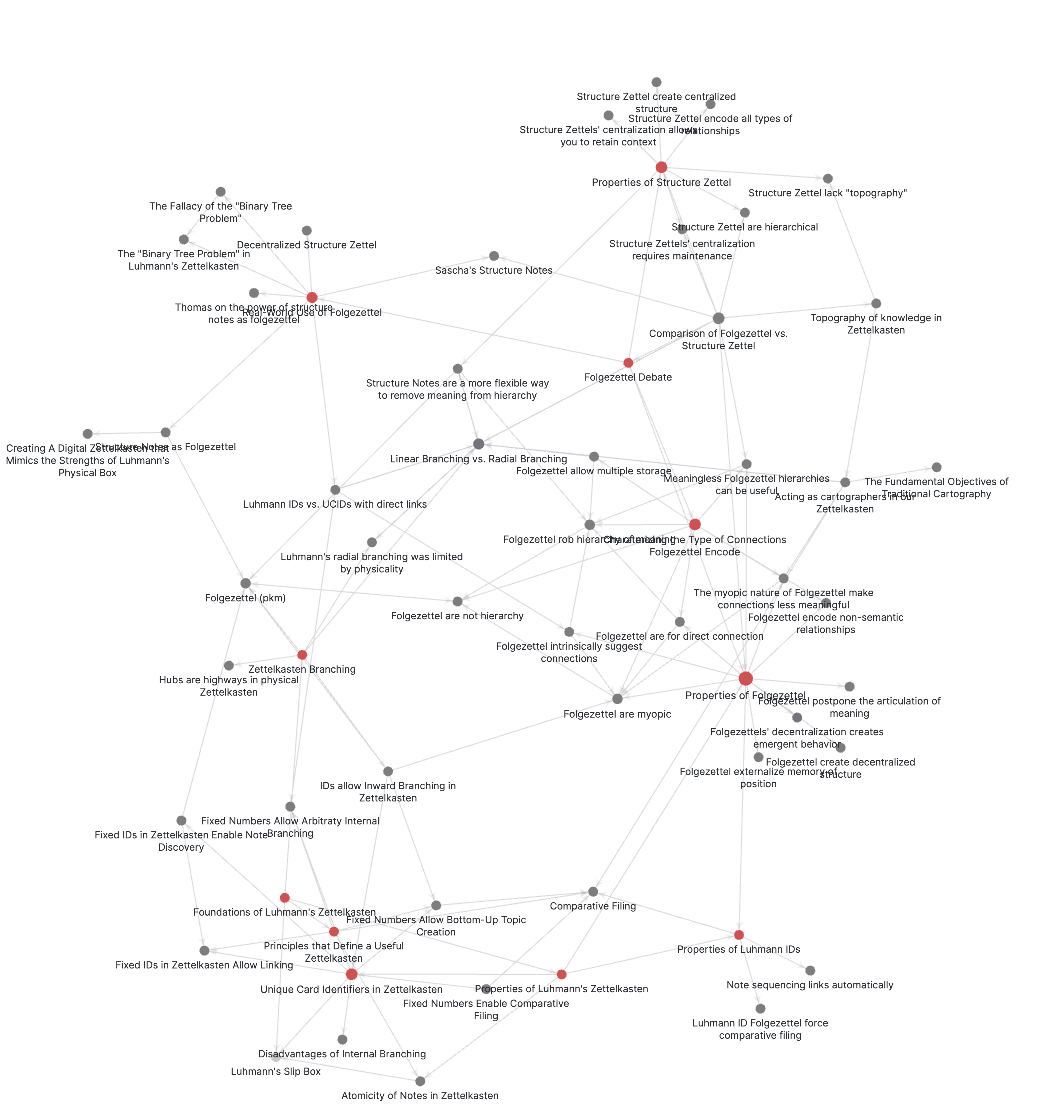

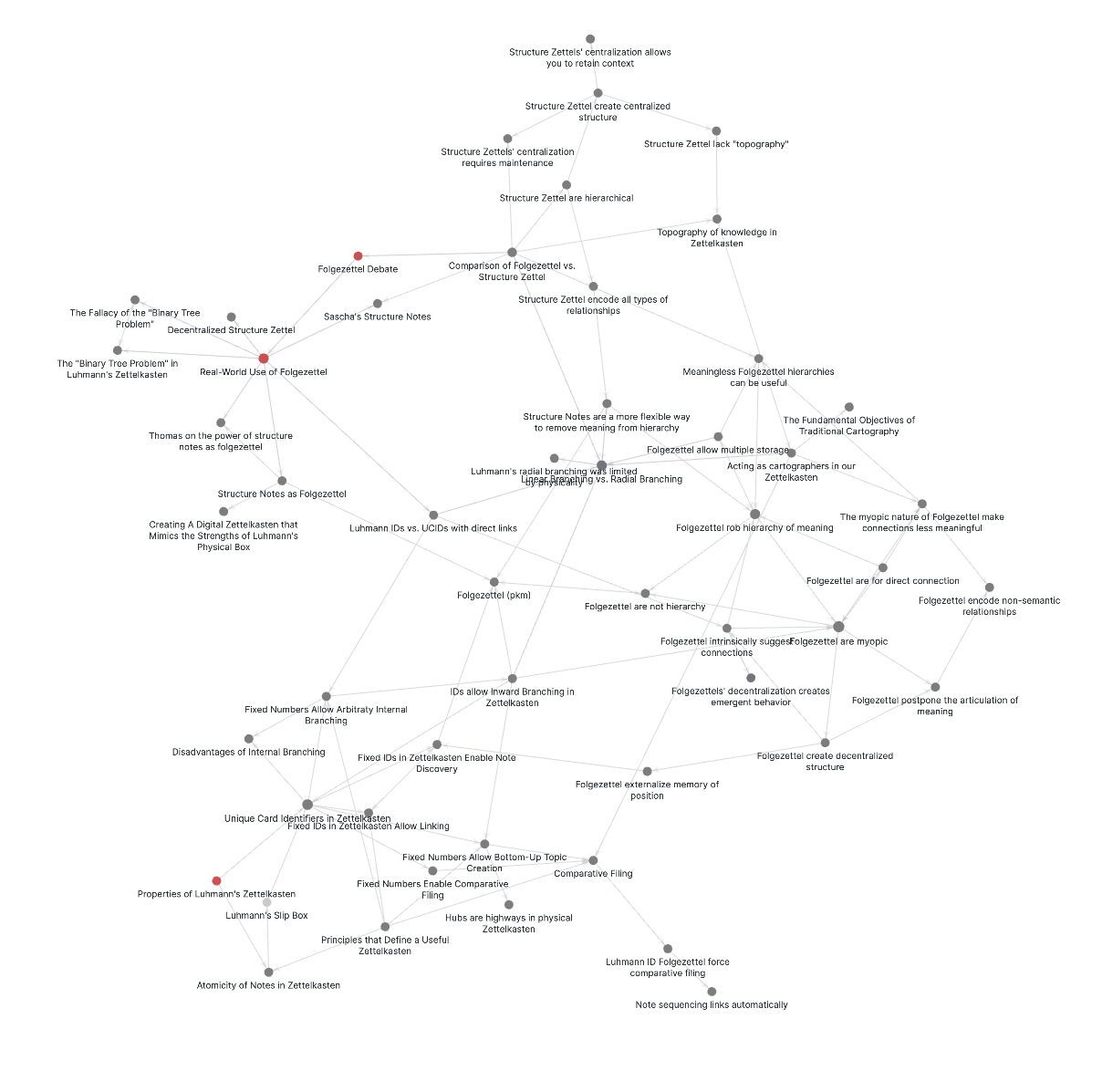

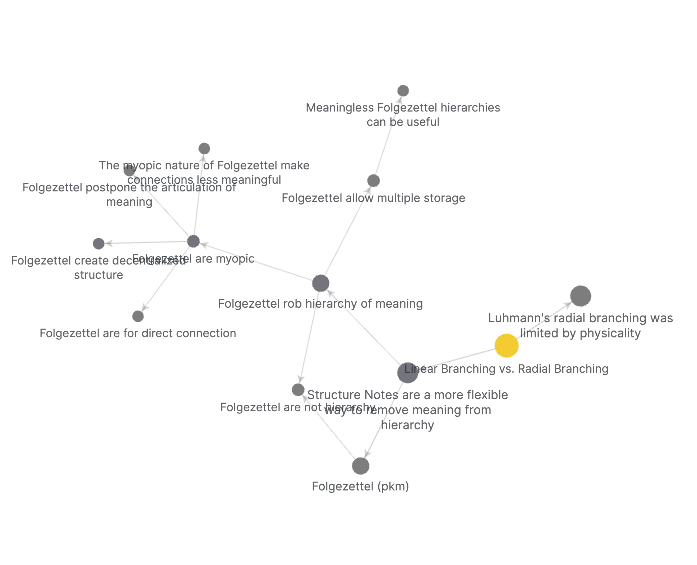

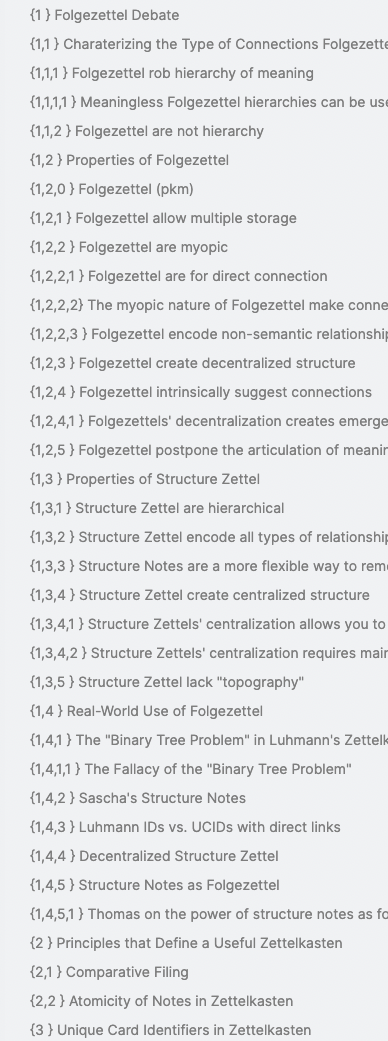

Prototyping an Archive with Three Different Structural Models

So, if our focus is on design, let’s play with some prototyping. In my exploration of The Great Folgezettel Debate, I made three archives that contain the same notes and approximately the same connections: one with Folgezettel titles, one with Folgezettel implemented using forwards-links, and one with Structure Zettel. I did not use time-based UIDs, as it wasn’t necessary for the scope of this project. I built these archives in Obsidian and visualized them using their graph tools. (I’ll also say that the archive is far from being an exemplary one. This is something that is truly a prototype for prototyping’s sake.)

(Download link for the 3 archives)

Here are the results:

Structure Zettel

Folgezettel implemented using forwards links

Folgezettel

Preliminarily, I would say that the local graph views are most useful in both Folgezettel conditions. In contrast, the global graph visualizations are most useful in the Structure Zettel and “forwards link” conditions. Of course, the list view is most useful in the Luhmannesque Folgezettel condition.

The feeling I get when using the archives to traverse the connections they contain is that Structure Zettel form a kind of “top-down” bird’s eye view. Knowledge is more obviously hierarchical and the structure feels most apt for constructing patterns and knowledge. It is very easy to look at the text of a Structure Zettel and follow a condensed line of thinking, the same way it’s easy to route from one city to another using a map.

When using both Folgezettel techniques to traverse, it feels like the Folgezettel form an on-the-ground “street view.” Knowledge, in this case, is more detailed and rich and it’s easier to see what a “next step” might entail as far as knowledge creation, argumentation, writing, etc. goes, the same way it’s easier to make a decision about what direction to turn when you’re on the ground, observing the environment at a particular location.

Closing

This is my first post in the forums and I have to say that it’s intimidating to jump into a conversation in such a committed, intelligent, and passionate community. I’m not sure if this metaphor is useful at all to you all, but I personally found it quite enlightening to have an apples-to-apples comparison of the different structural techniques I’ve been studying now for about a week.

Please, please let me know your thoughts and let me know if there’s anything I can clarify!

If you want to experiment with the data yourself, Austin released the benchmark notes on GitHub. – Each variant lives in another branch, so you need to know a bit about git or download each branch from GitHub manually. For intermediate git users, I suggest to put each branch into its own directory using git worktree.

Sascha’s Comment: This post might be the most inspiring and in-depth post on the topic I ever read. So, I want to thank @iamaustinha for that big time. These two concepts are close to the core of the issue: “top-down” bird’s eye and on-the-ground “street view”. I’d like to keep my commentary to a minimum and rather write an extensive discussion on your article. Disclaimer: I immediately went into my Zettelkasten and created a Structure Note on this topic (for the first time ever in this domain).