How to Track Your Writing Progress

There’s an interesting 8min talk by Brian Crain on optimizing productivity. Brian found tracking his progress useful:

I learned that having a continuous metric is enormously motivating since it allows you to continually improve yourself. These small, continuous changes make a huge difference over time.

You can only change and improve what you measure, the saying goes. It matters what you focus on, though:

Finally, tracking commitments has taught me how critical one’s mindset is. When I would slip into thinking of commitments as simple tasks, my success with that method derailed completely.

I tried to make sense of this for me and define what a task and a commitment is.

Think about tasks as one-off actions. You can complete them in a reasonable time.

A commitment is not easily checked off. If you were a professional author and want to write for the rest of your life, the commitment of ‘writing’ will never end. Besides life-long commitments, there are those which scale to a few years, like attending University and getting a degree. Then there are projects, to which you are committed to as well. My Zettelkasten book is definitely a project which I consider a commitment. My software development projects are long-term projects, too. All of these examples require multiple actions, or tasks, to be completed over some time. Life-long commitments don’t have an end built in, but the others do.

There doesn’t seem to be a minimum time required to declare something a commitment. Consequentially, smaller projects which take only a few hours to complete should also count as commitments. In my case, “work on the next blog post” would be such a day’s commitment. It’s also embedded in the large-scale commitment of running this blog. While Brian found taking note of daily commitments useful, I don’t think there’s a lot of benefit over calling these small projects. I want to reserve ‘commitment’ for something which is composed of different activities over a period of time longer than a single day, and which requires willpower or motivation to pick tasks up again and keep going.

Now that a commitment will take time and maybe even willpower, how do Brian’s findings help us achieve the ends we’ve committed ourselves to? How can we track progress to help reach our goals?

How to Track Writing Progress

Although Brian’s statement is much broader, I want to limit the practice of tracking to activities around writing, like blogging, writing a book, keeping up an academic publishing schedule, and the like.

If you are serious about writing, you should make writing a habit. To make writing a habit, it helps to track progress. We can fool ourselves, but data don’t lie. Tracking helps uncover when and how we’re slacking off.

I can think of two useful metrics:

- You can track how far your research progressed. In my case, the tangible and high-quality metric would be Zettel notes per day. (I hope you agree on this metric, and I hope you do take notes feverishly.)

- You can track how you fare in your writing project. Take note of your daily progress, measured in words, on a per-project basis. Also, it’s useful to keep an overview and count the words you got for each project. Larger projects justify a finer granulation: write down how many words you got for each chapter of a book or each section of an article.

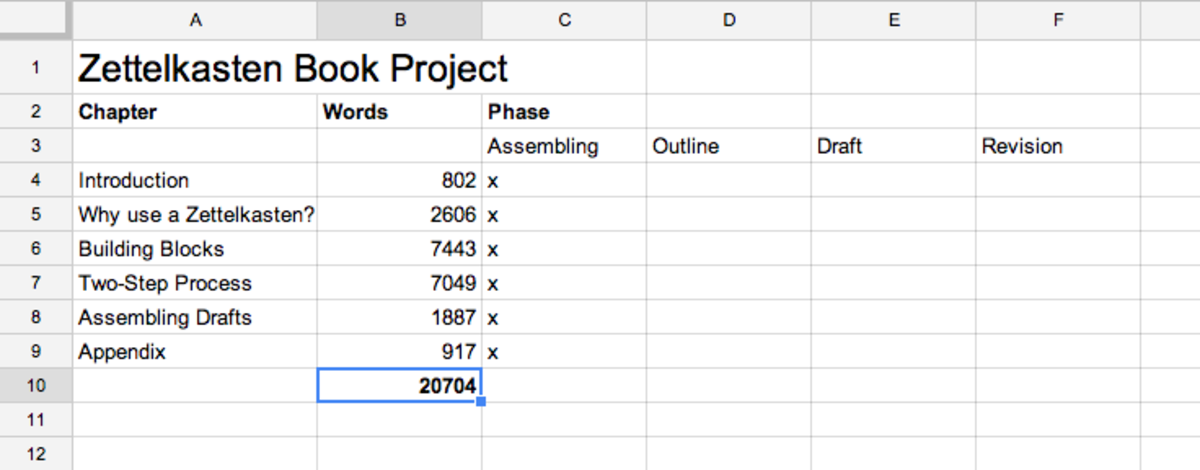

Only recently did I start to take note of my progress toward finishing the Zettelkasten book. You can find the most recent version of my spreadsheet online at Google Docs.1 It’s rather simplistic at the moment since it shows the chapters and their status only, but I already know how I would like to develop it. Up next, I am going to add each chapter’s sections to track progress on a more detailed level in a separate sheet. I’ll incorporate my writing progress log as another sheet.

I’m a fan of tracking progress in general. Most of the things I want to be better at can be tracked. This includes strength training, where I count the weights, repetitions, and sets of each exercise. It also includes my work: I can find out how many words I write each day and find out under which circumstances I can write the most. There are times during which I’m less productive when I try to write, but during which I can perfectly achieve something else.

Some people say that writing good-quality texts is more important than writing a lot. But being able to write a lot on a consistent basis is the first step to write good texts. You need to write anything to make it good, and given getting better at it requires practice, it is rational to start writing a lot. Consequently, counting your words each day to ultimately increase your output pays off in the end.

As soon as patterns emerge, it’s easy to optimize: put your quality work into the times you can concentrate easily. Put off mundane tasks to the low-energy times of day. Finally, don’t worry about the rest of the day and don’t beat yourself up for not achieving as much as you hoped for. You did your best already under the given circumstances. Adhere to the “work hard, play hard” mantra, schedule time to relax, and don’t worry about how much you did or did not achieve. With practice, your working hours will yield more results once you stop stressing yourself constantly. That’s the beauty of healthy time-management and tracking work: you both increase your efficiency and begin to value free time and start to work healthier.

I get paid for giving advice to fellow students at University. Sometimes, the coachees think keeping a daily progress log is a good idea and develop all kind of fancy metrics. Most of the time, though, they don’t keep up with it. All too often the reason to stop is: no one wants to be confronted with failure permanently. Some of my coachees aim too high and don’t want to face the fact they can only achieve so much in a day.

It doesn’t help to set a daily writing goal of 5,000 words if the most one ever achieved was 3,000. Tracking won’t make you faster or better. It can only make you more efficient.

My take-away from these coachings is this: don’t take the numbers personally. You’re not a failure because you had hoped to write more. Work on your expectations first, then continue to measure, and then try to find out what the numbers tell you. Do you write most in the morning? Then move hell to put writing hours in your mornings and stop stressing yourself about your waning productivity in the evening! Uncover patterns, guided by the numbers, and act accordingly.

- Did you try to track your progress in the past? How?

- Did you encounter the ressentiment that writing a lot doesn’t equal writing good texts, too? How do you respond?

-

I think it’s cool that I can share this data with you online, just like that, and satisfy everyone’s voyeuristic preferences. ↩