Building Blocks of a Zettelkasten

I am working hard on the “Building Blocks” chapter of the Zettelkasten book and I want to finish it first to show it to the public.

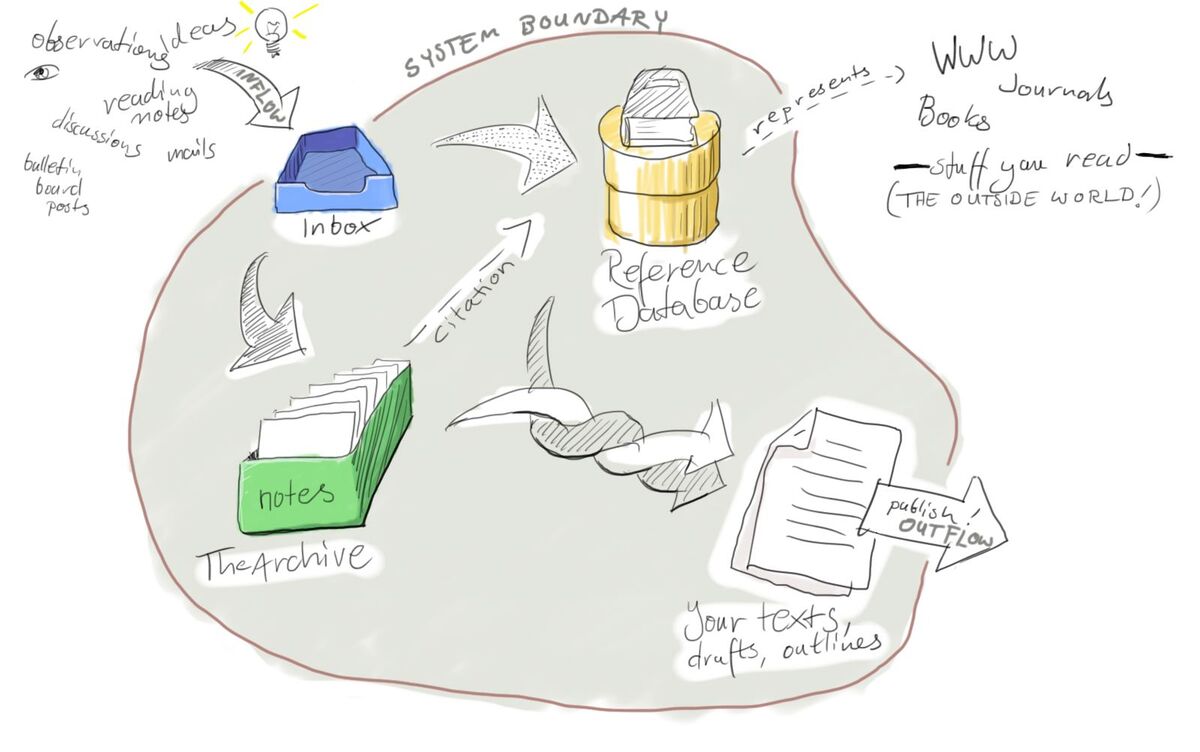

It covers all parts of the toolkit. To sketch a structure and talk about its components, I need to get the requirements and implementation done before talking about workflow details. Today, I want to show you a birds-eye view of the overarching systems metaphor I’m using in the book.

Honestly, I had hoped to finish the chapter this month, but my non-writing related workload has increased and thus delayed progress. I think it’s better not to promise anything big in advance. I will rather keep you up to date on the way to getting the chapter out.

State of the Book

Let’s talk about using the Zettelkasten as a system. Regarding this model, where am I now?

There’s a thing called “Zettelkasten”, and then there’s you using it. The former is the toolkit, the latter is your application of a method.

The Zettelkasten as a toolkit is a structure. We operate within its boundaries. It’s a systemic structure, since it’s composed of different tools (the system’s elements) which have a productive relation to one another. This structural perspective makes it easier to reason about the implementation requirements.

The Building Blocks chapter of the book is about that. I recognize the following pieces:

- Inbox: the gateway into your knowledge system

- Archive: the one, trusted place to look for information

- Reference Database: interface to the outside world

Also related are pieces of effective project management to get writing projects done. Your finished texts aren’t part of the system, though, because they don’t serve a function for the whole. They’re products which affect the outside world instead. This means if you find out something new during the writing process, you’ll have to create appropriate Zettel notes and not rely on the text you produced. Essentially, you have to treat your own writing like you treat texts by other authors: take note or you’ll suffer from Collector’s Fallacy.

When you are using the Zettelkasten toolkit, you are creating a communication system between you and the Zettelkasten. In short, you and your note archive can communicate with one another if the results your archive produces are sufficiently surprising and thought-inspiring. Leaving all this theoretical handwaving aside, this view essentially puts you as a user into perspective. It’s about the flow in “workflow”. While the Zettelkasten as a structure helps to identify its parts, thinking about your work with it this way helps to find out where the moving pieces are. What’s going to change often? Where are bottlenecks, restricting your productivity? This is about dynamics.

I’m iteratively getting a better picture of the Zettelkasten using the systems metaphor. The picture I show you today is still work in progress, so of course I’m interested in your opinion and I’d love to debate this model.

Zettelkasten as a Dynamic System

Let’s say you’ve got a toolkit of your liking: you’ve got something in place to implement all of the three Building Blocks, so there’s a “rigid” structure which you can rely on to create flow and output, which means you’re learning and writing. For now, take this structure for granted.

When you work with the toolkit, usage patterns emerge.

For example, you’ll always only put notes into your note archive. This sounds pretty stupid, but it’s an achievement to stick to this principle and not begin to put, say, shoes inside of a box with paper notes; or to put holiday picture files in your digital archive. You wouldn’t stir your soup with a hammer, either. It seems nonsensical to even think about it. There’s a reason for this: our desire to separate the application of our tools and our expectation that the separation is permanent and stable.

As soon as you sit down to work with the toolkit, you’re creating a bubble which determines what you may focus on as long as you’re working and what clearly is not part of the workflow. In other words, there is a boundary for the communication system you have with your Zettelkasten.1 Inside is your interaction with the Zettelkasten, outside everything else. The criterion to determine what’s inside and what’s outside roughly is this:

Can you or the Zettelkasten can come up with something interesting in the process?

Information is the Basic Unit of Your Throughput

The elements of this communication system are pieces of knowledge, or information. Basically, this means that either your memory or your note archive have to provide new information. Additionally, the information has to be relevant for your current thought process or writing project. I prefer “information” to “knowledge” in this case because talking about information implies that someone is about to be informed about something. It’s more active. You have to provide information, whereas knowledge can simply be kept.

This is what your note archive is designed to keep: pieces of knowledge. When you work with your note archive, you’re getting information. That’s because you won’t expect every result a search produces.

If there were no connections between notes, your archive wouldn’t be able to associate interesting and related things during your little chat. That’s why identifiers and stable links are so important, both for the note archive and for the reference database: you may want to have a life-long discourse with your Zettelkasten, so it better be designed to support this from the start. If you had to migrate to another software and lose all hyperlinks between notes, for example, it’s as if your partner suddenly suffers from some kind of amnesia. Simply put, it becomes rather useless.

That’s about it concerning change inside of the system. The Zettelkasten provides information and sparks new ideas. You, on the other hand, tell your note archive about your ideas so it can remind you about them next time.

There need to be interfaces to the rest of the world to promote change in the system. Without inflow, there would be no change and no growth; without outflow, any growth would be rather pointless or a time-waster. The inflow consists of information you put into your inbox. The outflow consists of your writings.

While your note archive will most likely be private, you’re going to write and publish articles, books, or blog posts. In your publications, you put a frame around a part of your web of knowledge, and make it accessible so others can benefit from what you’ve learned.

I decided not to add a chapter on the actual writing, since your finished writing projects are already outside of the Zettelkasten system boundary. However, when you compose a draft you likely produce more knowledge in the process, so we will certainly deal with completing drafts:

- how to work with notes to write texts,

- how to outline using the Zettelkasten, and

- how to collaborate with others.

As I pointed out before: when the outline is finished and based on Zettel notes, there’s not much left to do to finish a first rough draft. Looking at it this way, I’m not really leaving you alone with your writing projects. It’s just that the product itself isn’t going to be inside the system’s boundary anymore.

The takeaway: you have to feed your note archive with useful information to promote growth in the system and thus make the discourse with your Zettelkasten more interesting. This continuing discourse will lead to new insights which (1) again become part of the system, and (2) will inspire you to write texts and produce output.

Crossing the Boundary with Text References

Besides inflow and outflow, there’s another way to cross the system boundary. While your own activity, reading texts and taking notes, is feeding the note archive, the reference manager provides pointers to stuff in the outside world, like books, articles, and web pages – that’s why it’s called reference manager.

It’s an outward pointer, albeit it’s just a weak link. What could a strong link look like?

Imagine what it’d be like to not use references. Then you’d have to write in the margins of the books you read, or stick notes between the pages, to make clear where your annotations belong. While that’s how most people actually read and annotate texts, it’s not promoting growth of the knowledge system, because the annotations stay outside permanently. That’s an example of a strong link: you’ll have to schlep the books around with you and skim through them if you want to access your own thoughts ever again.

It is a really clever technical solution to the problem of keeping annotations to print page numbers in texts if you think about it. As long as you’re able to identify the text and the location inside the text, you can put notes wherever you want; you can work with it without relying on the physical book as long as the reference indicator is attached.

The takeaway is this: translate stuff from the outside world into something your system can understand. A book, physically, cannot be part of your Zettelkasten. Your personal library isn’t part of it. A representation of a book will fit in nicely, though. Since you own the representation, you can work with it more freely, too.

Conclusion

Talking about the book preview makes me nervous: this will be my very first information product, written in a language which is not even my first. Thanks to all of you so far for giving back and telling me about how you work. I learned a lot from you already.

I’m open to debating the system’s architecture, so tell me what you think of it. With the help of your feedback, I’ll be able to make the model and the book better.

- How appropriate does my sketch of the system appear to you? What’s missing?

- What would change if you thought about your knowledge work in a systemic way?

- Would you work differently, for example? Would it help if the boundaries were clear and the concerns of the tools cleanly separated?

-

Usually, people at University would punch me in the face for stating the relationship in this way. When you talk about social systems, there’s no “You” and “I”, because actors and people don’t fit in the model. There is only pieces of “communication” which operate with the abstract currency of “meaning” and relate to one another, forming strands. But we’re not doing sociology here, so let’s not worry about this. ↩