How to Improve Your Zettelkasten by Learning from Athletic Training

The benefits of your Zettelkasten highly depend on the longevity of each note. Since the Zettelkasten as life-long companion and comrade in the battle for and against knowledge is a long-term endeavor, it is crucial that you create notes and structures that will last a long time. The minimum goal should be that they last a lifetime, so they are optimally designed for yourself. Ideally, they last forever, so future generations can benefit from your work as well.

One of the major benefits of the Zettelkasten is that you can transcend time to a degree. You can connect your current ideas with thoughts that you have had or read about 20 years ago.

Luhmann himself wrote:

Das Problem des Lesens wissenschaftlicher Texte scheint darin zu liegen, daß man hier nicht ein Kurzzeitgedächtnis, sondern ein Langzeitgedächtnis braucht, um Bezugspunkte für die Unterscheidung des Wesentlichen vom Unwesentlichen und des Neuen vom bloß Wiederholten zu gewinnen. 1

The challenge of reading scientific literature is that you need a good long-term memory to distinguish the important from the unimportant and the new from the repeated.

The presupposition for transcending time is that you write notes and make connections that are understandable for the rest of your life at minimum, and optimally for other people as well if you want to share your ideas. So I wrote an essay on how to achieve this in 2015. However, I didn’t have the coaching experience that I have today. When @Carriolan asked a question, I came up with a better explanation:

Practice General and Specific Skills Like an Athlete Does

@Carriolan said:

[T]he body of a Zettel should be structured / segmented, so that new ideas may be refactored to either existing notes or new notes without the necessity of rewriting the original note. […]

This is a correct summary of my position. But how do you achieve this? The short answer is:

How to achieve this is not part of the Zettelkasten Method itself. Rather, it is a byproduct of having a coherent model of the type of content you produce and adhering to it (updating is necessary).

In the essay of 2015, I came up with an example of how I structure notes that are about hormones: The structure is guided by a metamodel. The metamodel is the Stock-Flow-Model I took from Donella Meadows’ awesome book Thinking in Systems. If I had no access to the metamodel, no experience in learning and thinking about hormones and signaling within the body (I even expect to make some mistakes leaving the coarse realm of hormones and diving more into the fine realm of intracellular signaling) and if I had little or no experience in learning something pretty unfamiliar, I wouldn’t have been able to come up with a note structure that is robust against time (and therefore new information).

Being able to produce robust note structures and connections is based on your personal skill in coming up with robust models and/or metamodels that are useful to the domain of the knowledge at hand.

So there are two components that together make up the skill of writing notes that stand the test of time (and therefore new information):

- Your access to robust models for the domain at hand.

- Your skill and knowledge of the Zettelkasten Method.

In some way, it is easier to learn the Zettelkasten Method as a student writing a seminar paper than being an expert with established but mostly intuitive and idiosyncratic workflows.

A student’s major obstacle is that they have to learn both the domain-specific skills and the Zettelkasten Method. From my experience, though, it is easier to build something from the ground up than being an expert who is unconscious of his own skills. It is easier to deal with the known unknown than with the unknown known.

Additionally, a major learning resistance of experts against the Zettelkasten Method stems from the necessity to change something that feels trust-worthy. This is a perfectly reasonable resistance since the risk of wasting time and effort on something from which you potentially benefit is real. Why should you risk missing deadlines, putting time and effort into re-learning what already seems to be working fine or even exceptionally well?2

If you put the Zettelkasten Method as a highly general tool for knowledge work on one side, and specialised techniques of problem-solving and thinking on the other, you can compare this dichotomy to athletic training.

In athletic training, this dichotomy is captured by the model of training specificity: If you want to box or perform as a linebacker in football, you need to train this specific action if you want to get the most bang for your buck. That means that you imitate what you are doing in competition as closely as possible (while at the same time being as safe as possible. Don’t go all out on each other in training!). On the other side of the spectrum, there are general training modes like running or cycling for endurance, weight lifting for strength and more. It seems to be optimal to do both, specific and general training. But why?

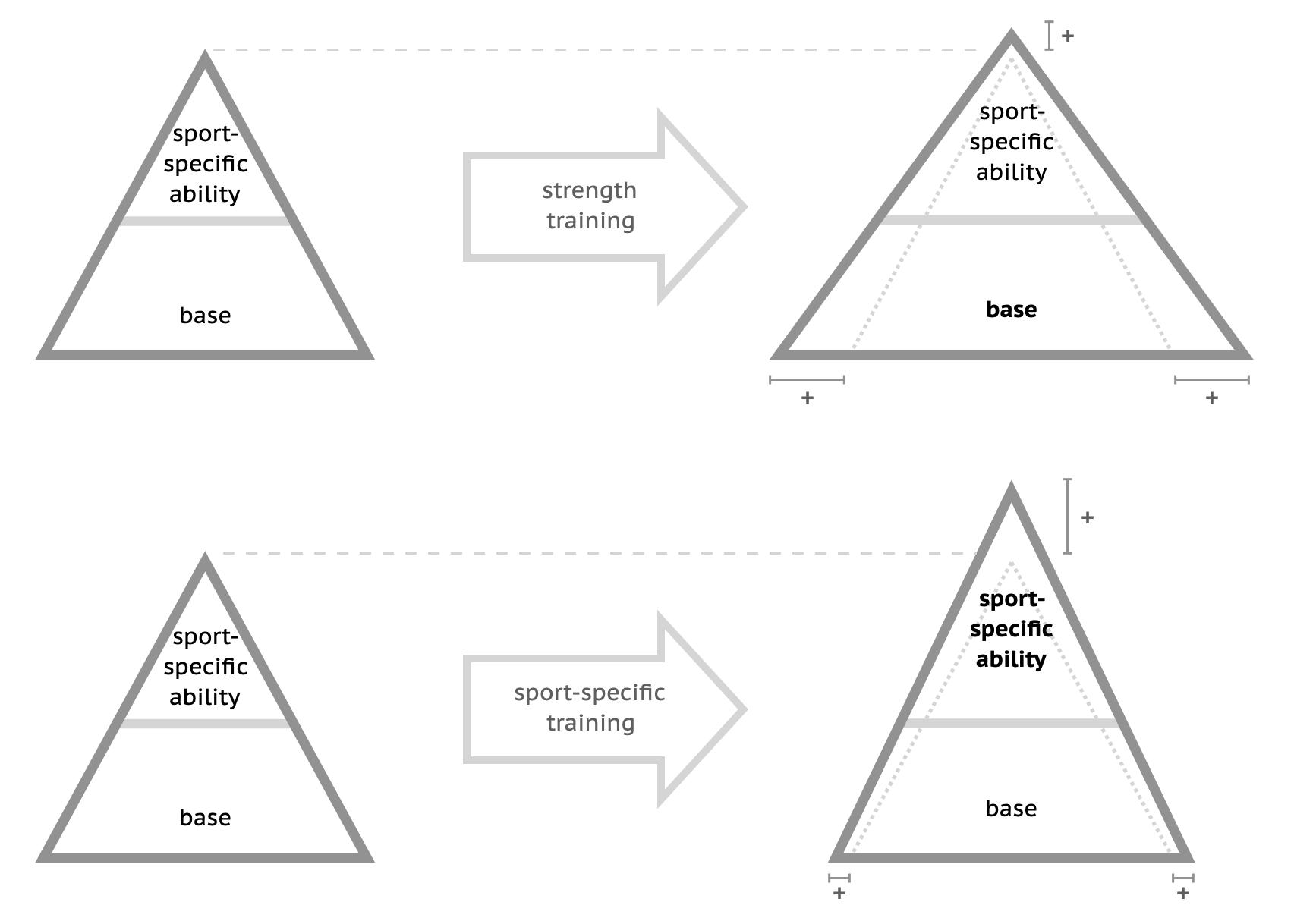

One of the major reasons is that you can build a higher pyramid if you make the base of the pyramid wider. The base of the athletic pyramid is in part composed of the optimal amount of muscle. If you are an athlete, your sport is not the optimal way to build muscle, for example. Weight training is way better. So by adding weight lifting to your routine, you can build your base. With bigger glutes and legs, most of the time you will be able to sprint more explosively, and with a thicker neck you reduce your risk of injury.

You can think of the Zettelkasten Method as the base of your pyramid as a thinker and/or writer. To become a better thinker and/or writer, you need to push yourself in the specific domains you’d like to improve. It might be a shock to you but the Zettelkasten Method won’t improve your ability to analyse a genome, or to create a more appealing exposition of your fantasy world. However, it allows you to transcend time when you access the ideas you thought about during your lifetime. It offers possible connections between ideas. It offers the opportunity to improve your understanding of an idea through reformulative writing.

What is the verdict then?

Understand the mechanisms that make a note robust. Like an athlete who needs to connect the benefits of general and specific training to optimise his abilities and success, you need to optimise general aspects of your work, like deliberately designing good notes for your Zettelkasten, and specific aspects of your domain, to optimise your Zettelkasten for your own needs.

That includes deliberately investing time and effort to become conscious of what you are doing intuitively. Sometimes, it even requires trust that you will need to make short-term sacrifices for the long-term benefit. But using the present to make a gift to your future self is the only rational way forward. So, you have no (good) choice anyhow.

Christian’s Comment: I noticed a lot of friction in my daily practice after a couple of years with my Zettelkasten: whenever I was building up more and more content on a topic, eventually I found that the sheer mass of it made the department in my Zettelkasten hard to use. Investing time into the Zettelkasten Method, not just the contents of the Zettelkasten, improved things: I tried different types of overviews, and by comparing my stuff with Sascha’s, who has totally different problem domains, began to adopt other tools he came up with – what we would eventually call “structure notes” here on the blog. These improvements don’t just happen. In the words of Stephen Covey: I needed to sharpen my saw.

-

Niklas Luhmann (2008): Lesen Lernen, in: Schriften zu Kunst und Literatur, Suhrkamp. ↩

-

Tim Ludwig, a client of mine, brought up this point. If you are a physicist in the academic realm, you cannot risk to fall behind the Darwinian publish or perish fight for survival. I credit him to be aware of the need to lower the time and effort invested to start a Zettelkasten. (This includes recommendations of how to plan a week, fitting the Zettelkasten Work in such a manner that even ending up not using the Zettelkasten is an acceptable outcome.) ↩