Don't Dehorsify the Horse

The Zettelkasten Method seems to get more and more popular. With popularity of methods there always comes a problem: Overzealous Orthodoxy. Some people, for various reasons, try to state what a Zettelkasten is and what not.

A good example is the use of categories: Do you have a Zettelkasten if you use a Zettelkasten? Some people argue that you wouldn’t have a Zettelkasten if you use a Zettelkasten and the very point of a Zettelkasten is to ditch the categories.

I personally agree, that your Zettelkasten will benefit a lot from ditching categories. But there is a technical problem with stating that X is not Y if some trait is missing.

We will dip our toes in the cold water of what I call concept work. The goal is not to find the true and only definition of a Zettelkasten but to become more competent with the usage of concepts. After all, how can you process concepts which are one of the main knowledge structures you find in texts when you don’t know anything about their nature?

The difference between the dead and the living concepts

In contrast to other approaches, Luhmann decided against making his Zettelkasten stiff and opted for an organic approach. There’s a reason his own manual is titled “Communicating with Slip Boxes”, and not something like “A slip box as a writing and thinking tool”.

Our starting point to understand the nature of the Zettelkasten Method is that it is an organic and non-linear, – even alive ,– approach on note-taking. This is not a clear-cut definition, because, in real life, there cannot be clear-cut definitions.

Take a look at the following way to define a horse: A huge animal with a head shaped like this and that, with four legs and so on and so forth.

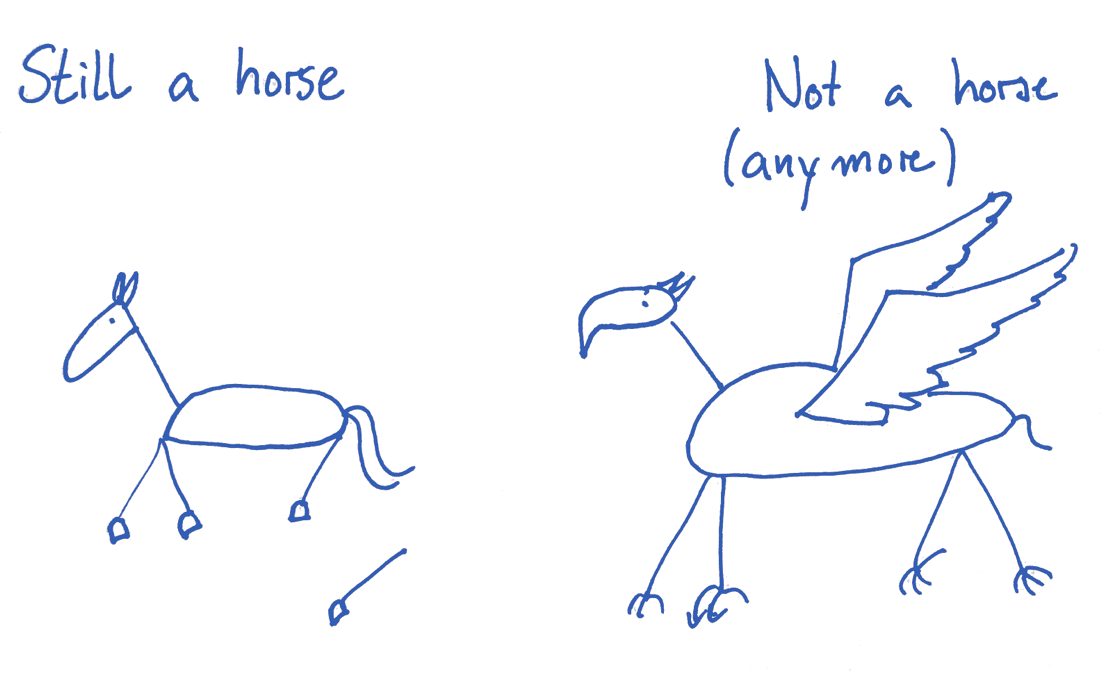

Even if we expand this definition to a point we all would agree on it, what if we amputate a horse’s leg? Do we de-horsify this poor animal? No.

Even concepts need a life of their own. We can use the concept of horse without ever encountering a clear-cut – but lifeless – definition. Lively concepts work by the concept of sufficient familiarity. The horse with the amputated leg, which has fully recovered from the operation and goes by the name Eagle’s Wing, if you worry, is accepted as a horse because it is sufficiently familiar to our general concept of horses. But if you alter too much of its traits, you will not be able to call the result a horse and keep a good conscience. Then it might be a griffon.

Hard definitions are dead concepts. If you change one part of it you change the whole thing. But most concepts are alive. Nobody with the right mind would think that the poor three-legged animal is dehorsified.

Nassim Taleb calls the this fallacy “platonification”: you are of making platonic what is not platonic by nature. Or in layman’s terms: To mistake some dead abstract theory about reality for reality itself. (One could argue that the main message of his Incerto is: Do not platonify, live in the real world.) This abstract thought can be illustrated by a quite funny example: Never cross a river that is 50cm deep on average. Why? It might be mostly shallow creek of 10cm depth, followed by a nice deep hole for you to fall into.

The Zettelkasten Method lives

The Zettelkasten Method is a living concept. Although there are traits that are more important than others, the Zettelkasten Method is more a set of useful principles and a spirit that came to being in Luhmann’s wooden demon he called his communication partner.

If someone tells you that your Zettelkasten is not a Zettelkasten, just refer him to the late Wittgenstein and send him a three-legged horse. It might not solve the issue but bring some peace to your mind.