Feynman's Darlings – Or: How Anyone Can Become Brilliant

You can become brilliant. You just have to be smart and work hard.

You asked me if an ordinary person by studying hard would get be able to imagine these things like I imagine. Of course! I was an ordinary person who studied hard. Source

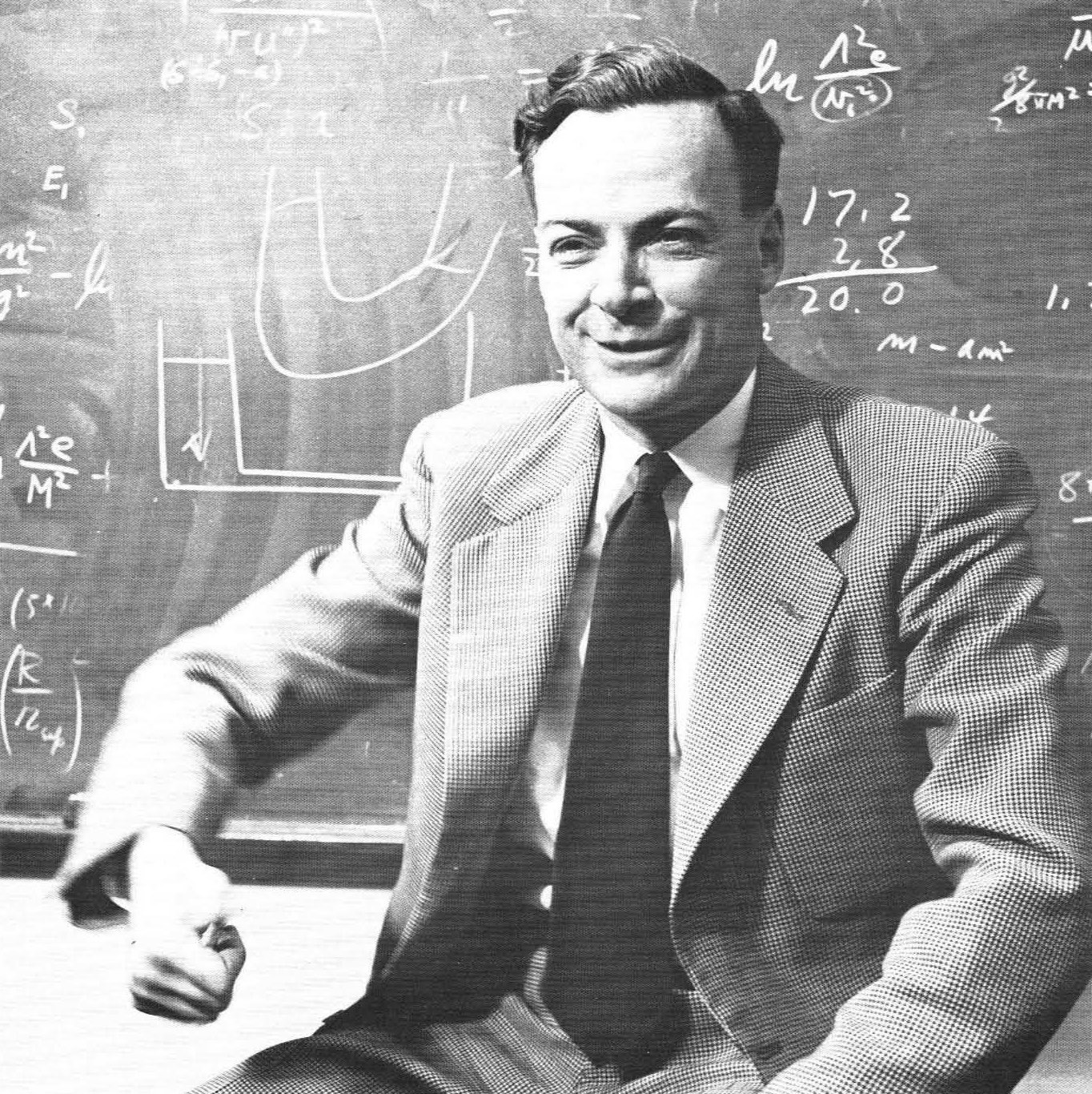

There is a good reason why Feynman is a legend that hardly anyone writes about: Feynman was a genius with a banal IQ of 125.1 His brain, the hardware of his thinking, apparently did not have the makings of genius.

Feynman’s genius was not given, he worked hard for it. Feynman is a legend because he not only gives us ordinary people the hope of rising far above ourselves. He even gave us tools to make us more brilliant. Feynman emphasized hard work. But you have to acknowledge his cleverness.

What do I mean by cleverness? Cleverness is the wise use of the mind. The following anecdote beautifully illustrates the difference between intelligence and cleverness:

In the race to the moon, the U.S. and the Soviets discovered that their ballpoint pens did not write without gravity. The U.S. developed a $10 million ballpoint pen that could do it. The Soviets took pencils.2

Feynman didn’t just have a method of understanding, the now so-called Feynman Technique. He had a clever system for increasing the probability of having brilliant ideas: The 12 favorite problems. Nassim Taleb would love this technique: It uses antifragility as a mechanism.

What is the method of the 12 favorite problems?

This technique is another demonstration of Feynman’s genius. It is simple and efficient:

- Maintain a collection of 12 favorite problems.

- Whenever you learn something new, check if it helps you with one of your 12 favorite problems.

Richard Feynman was fond of giving the following advice on how to be a genius. You have to keep a dozen of your favorite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lie in a dormant state. Every time you hear or read a new trick or a new result, test it against each of your twelve problems to see whether it helps. Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say, “How did he do it? He must be a genius!”3

That’s all!

Part of the genius is in the simplicity of this technique. The other part of the genius is in the use of antifragility.

How antifragility allows for genius

Antifragility is a term coined by Nassim Taleb. He even dedicated his magnum opus4 Antifragility5 to it. Antifragility is best understood in the context of three possible relations to randomness and ultimately time:

There are things for which randomness and time are negative risks. For example, a vase can only lose when confronted with randomness. Playing children are never good for it. The longer the vase exists, the more likely it is that it will be destroyed. It is fragile.

But the opposite of fragility is not robustness in the sense of mere resistance or indifference to randomness and time. The warning label on a package “fragile” is the instruction: don’t throw it down, don’t shake it. Ultimately, it is “touch as little as possible.” But the opposite is not “Do what you want!”. It would be the instruction to throw the package intentionally, to shake it and to handle it as much as possible. Only that is the opposite of fragility.6 So the three terms come to state:

- Fragile is everything that loses from chance and time.

- Robust is everything that doesn’t care about chance and time.

- Antifragile is everything that benefits from chance and time.

Limiting the possible costs while keeping the possible upsides is one way to make a system antifragile. You protect the system against catastrophic events, but let it fully benefit from anastrophes.

This is the mechanics behind Feynman’s 12 favorite problems: everything we learn becomes an opportunity to be an important step toward solving problems important to us. If we learn something new, we can test that new thing for its usefulness to our 12 favorite problems. Each time we go through the list, it costs us very little time and energy (low cost). But each time we have the chance to take a giant leap toward the solution (anastrophic consequences).

Without the 12 Favorite Problems, these opportunities would likely slip through our fingers. In a sense, this system guarantees our chances of seizing these opportunities.

In short, having 12 favorite problems is a clever system to increase the probability of having brilliant ideas.

How to find your 12 favorite problems

- Make a list of the areas of your life. These will serve as your backbone for your later thinking.

- Use an outline or mind map as a creative technique. You can use any creative technique. Now it is only a matter of producing for the time being. Collect all problems and possible projects that seem interesting to you in some way. Sort everything into groups. Try to find patterns.

- Throw out everything that does not inspire you.

This method is only a suggestion! All good methods follow these two meta-rules:

- Collect first without judging.

- Then sift out the gold pieces.

Additional tips and tricks

12 is not a magic number! It doesn’t matter how many favorites you have. Yet, there should be no completely inactive favorites.

Not all favorites are problems! I don’t phrase everything as a problem. For example, I am writing a collection of short stories set in a prison valley. It is also part of my list of favorites. I think Feynman has 12 favorite problems because as a physicist, you mainly solve problems. But as a writer, you don’t only solve problems, you write texts. There are different types of opportunities, not just problems.

Particularly relevant favorites are your life goals! Need help finding your favorites? Make a list of all your life goals. Which of your collected problems and projects are especially relevant to your life goals? The more important a life goal is to you, the more the problems and projects related to it inspire you.

You don’t know what your areas of life are? No problem! Here is a list of possible responsibilities in your life:

- Personal

- Physical health, robustness and fitness

- Mental health, robustness and fitness

- Spiritual health, robustness and fitness

- Occupation and career

- Material prosperity

- Home and homeland

- Spirituality and faith

- Social life

- Partnership

- Family and friends

- Friends

- Enemies

- Community

As a knowledge worker, you have it easy! The field of “job and career” can produce a large number of darlings. After all, your profession is to deal with problems or knowledge-based projects.

How to build the darlings into your workflow.

Richard Feynman kept the problems in his head. I see this as a possible source of error. After all, one can also forget important things. I know that only too well from my own experience. Thus, it is better to build the favorites into your own workflow.

Of course, I build them into my workflow with the Zettelkasten:

- When I create a new note, I write and link it as usual.

- Then I call up a saved search in The Archive via shortcut.

- I then go through the notes of my favorites and see if the fresh note is usable for one of my favorites. In doing so, I make an effort to find a connection. This effort trains my divergent thinking.

- Afterward, I try to understand the nature of the connection from the fresh piece of paper. In this way, I train my convergent thinking.

My favorites right now (2022-12-31) are the following:

- FAM Valeria

- FAM Pregnancy and infants for fathers

- ZKM The Nootropic Day

- ZKM Getting Things Created

- ZKM Thinking Tools

- ZKM Mindmapping Software

- MEI Arm wrestling training

- MEI Monk mode

- MEI ME-Improved for soccer players

- MEI WODs

- MEI Exercise Catalog

- D&P Party Program BAAP

- ME Learn to draw

- ICH World crafting

- ICH Enligunon - The prison valley

- ME Living with the dog

(The title prefixes are for scanability, FAM = family; ZKM = Zettelkasten Method; MEI = ME-Improved; D&P = philosophy; ICH = hobbies)

As you can see, my favorites are not only problems. They also include projects and topics. I am not a physicist who mainly deals with solutions to problems. I am a popular scientist, trainer and hobby writer.

Another place where you can use the 12 favorites is your task management. Check if something helps you with your favorites when you empty your inbox.

Summary

- Feynman was smart. He was so clever that he was able to overcome his mind with his cleverness in understanding how to think.

- Feynman’s favorites are a technique to increase the number of brilliant ideas.

- It accomplishes this by increasing the number of chances for high success with a low investment of time and effort. (Antifragility)

- Build your own list of favorites to benefit from this technique.

And remember the optimistic message Feynman gives us: any of us can be brilliant.

Christian’s comment: When I create a new note, I don’t immediately know where it might fit. I have to be careful to check various projects or contexts mechanically to see if the new note fits them. Otherwise, I forget these projects completely for a while. These are missed opportunities that I am regularly annoyed about. So: I have to create more chances with a small, mechanical check.

-

https://www.cicero.de/kultur/iq-tests-intelligenz-der-mythos-hochbegabung/60823 ↩

-

Unfortunately, the anecdote is not accurate. https://www.thespacereview.com/article/613/1 ↩

-

Gian-Carlo Rota (1997): Ten Lessons I Wish I Had Been Taught, Notices of the American Mathematical Society 1, 1997, Vol. 44, pp. 22-25. ↩

-

Nassim Nicholas Taleb (2012): Antifragile. Things that Gain from Disorder, St. Ives: Penguin Books. P.13, P.14 ↩

-

Affiliate Link. I get a small commission from Amazon if you buy something from Amazon through the link. ↩

-

Nassim Nicholas Taleb (2012): Antifragile. Things that Gain from Disorder, St. Ives: Penguin Books. S.31/32. ↩