Include Images in nvALT for a Multi-Media Zettelkasten Experience

nvALT sports features which are not so well-known. You can make it work with an image repository to easily include images in your Zettel notes. I don’t make heavy use of the preview at all, but when I do, it’s mostly because I want to take a look at images. For this purpose, I decided to stick to a simple folder structure and customize the preview template to work with it.

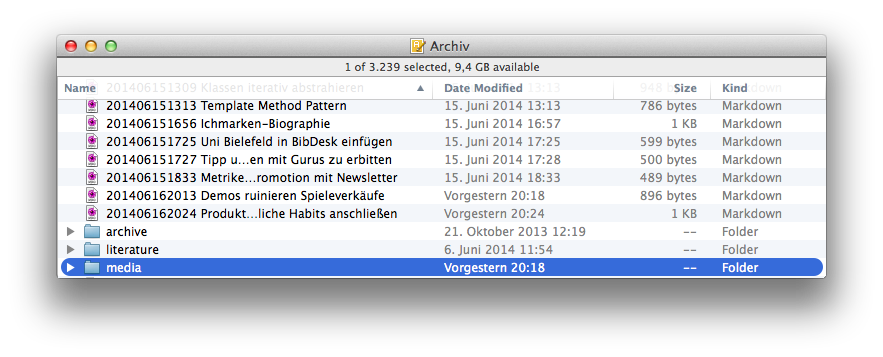

My Zettelkasten note archive is one single folder on my disk which I watch with nvALT. As depicted, it contains the following:

- a bunch of Zettel notes to view in nvALT,

- a “media” folder with mostly pictures,

- a “literature” folder with my reference database,

- and an archive of notes I don’t need anymore.

The path of my archive is /Users/ct/Archive/. Any sub-folders, like “media” and “literature”, are invisible to nvALT itself.

Using relative paths, I can point to their contents. From a note’s point of view, the path media/some_picture.png makes sense:

Systems can use either absolute or relative paths. A full path or absolute path is a path that points to the same location on one file system regardless of the present working directory or combined paths. It is usually written in reference to a root directory.

A relative path is a path relative to the working directory of the user or application, so the full absolute path will not have to be given.

— Wikipedia on “Path (computing)”

So when /Users/ct/Archive/ is the working directory of nvALT and the base directory of any note in it, media/some_picture.png becomes a path component relative to this working directory. Combined, the full path to the image, taking the working directory of nvALT into account, equals /Users/ct/Archive/media/some_picture.png.

The thing is, nvALT doesn’t pass its working directory through to the preview. The preview is a HTML file which resides in a temporary folder far away. Any relative path would be relative to this temporary folder instead of the archive. Thus, relative paths don’t work so well out of the box.

However, we could use absolute paths. I don’t like that idea, though.

Why you should care about relative paths

Absolute paths will work just fine – until I change the location of the Zettelkasten note archive from “Archive” to, say, “Zettelkasten”. I’d have to search and replace all paths references in every file.

Access to my media sub-folder is limited by nvALT’s preview feature, only. From the point of view of any note file, the working directory is the archive and relative paths are treated as paths relative to the note file’s containing folder. Relative paths don’t work in nvALT because there’s a limitation in the application, not because there’s anything wrong with the notes.

To use absolute paths is a pragmatic short-term solution while relative paths would be the better choice if the application only handled the note preview differently.

From an “ontological” point of view, relative paths are the right thing to do: they take into account only the structure of the note archive and its sub-folders. These sub-folders are important attributes of my archive. The application which provides access to the folder isn’t. It’s just a coincidence that I happen to like nvALT.

If we design a Zettelkasten note archive, the archive itself should always come first. Application-specific limitations aren’t worth to consider most of the time because the archive itself will likely survive the software. That’s why I think proprietary file formats kill the longevity of your Zettelkasten.

In other words: all information in the Zettelkasten is made to be timeless. This includes meta-information like paths. Don’t water down the significant feature of timelessness by pouring in platform or application specific limitations just because they make it a little more convenient. The long-term cost may be higher than you think.

The good news is this: nvALT provides a workaround so we can indeed use relative paths.1 Hooray!

Including images in nvALT’s preview

nvALT can be configured to use relative paths in the preview. Here’s how.

- You have to configure the preview template to take the absolute path of our note archive into account.

- The template is located at

~/Library/Application Support/nvALT/template.html.2 There may not be a file calledtemplate.html. There might not even be a folder called “nvALT”. In this case, grab the handy download script I put online just for you. If you follow this link, you’ll see a command you have to copy and paste into your Terminal.app. Afterwards, the template will be in nvALT’s support directory. You may not see the “Library” folder in your Mac user’s home folder, but it’s there. Just select “Go > Go to Folder …” from Finder’s menu and insert the path~/Library/Application Support/nvALT/there to travel to this hidden location. - If you didn’t download my template file, you have to edit the

template.htmland add the directive to set a base directory when doing file operations like including images in the preview. Put the following right before the</head>closing tag:<base href="PLACEHOLDER TO YOUR PATH">

Update 2014-07-12: If you open the HTML file with TextEdit, please ensure that TextEdit displays the HTML code and not a pre-rendered output of the contents. - Either way, you have to put the absolute path to your archive where the placeholder is. Mine is called “Archive” and sits right in my home folder. Since my user name is “ct”, the absolute path becomes

/Users/ct/Archive/. Prepend it with thefile://protocol,3 which makes for three slashes after the colon. In my case, the full path is:file:///Users/ct/Archive/. Copy and paste this address into your web browser. It should show you the folder’s contents. If that works, you got it right.

This way, whenever I include an image, it is assumed to be relative to the base directory /Users/ct/Archive/. Since my images are collected in the “media” subfolder, I can write this in Markdown:

This automagically becomes /Users/ct/Archive/media/201406180939_a-chart-of-something.png in the preview.

You see that I add an identifier to the image files, too. Thanks to nvALT, I can see images in a note’s preview. But everywhere else, I don’t assume that previewing an image will work. By giving the file a global, system-wide identity, I can reference it by identifier like I usually do. It could look like this in my book manuscript, which is someplace else:

It's important to take a closer look at something.

See the following chart `<!-- TODO include image §201406180939 -->`

Here, I left a comment4 or annotation for myself which tells me I have to include the image with ID “201406180939” in the final draft. By convention, I can guess that the image is in my Zettelkasten “media” subfolder, which becomes a central repository for graphs and charts.

It doesn’t become an image repository simply because I need some place to put images. It becomes a repository for useful stuff only. If an image seems important, I take Zettel notes and use the image already. This way, the image has to stay in the “media” sub-folder of my note archive anyway.

-

Even if it didn’t, I wouldn’t care. Maybe I’m a bit extremist when it comes to my Zettelkasten, but I’d rather use relative paths with no effect than losing ground to the app because it imposes weird limitations. Software can change later, but a knowledge archive shouldn’t. ↩

-

If that folder doesn’t exist yet, you have to go to

~/Library/Application Support/instead and create a folder called “nvALT” yourself. The exact capitalization is important. You can find the templates you have to copy there inside the application bundle:/Applications/nvALT.app/Contents/Resources/template.html. To get there, right-click the nvALT application icon in your Applications folder and chose “Show Package Contents” to have a look at the resources bundled with the executable application. Then copy the file from “Contents/Resources/”. ↩ -

You could use another protocol like

http://instead, and fetch every image from your own website, for example. This should work, too. I didn’t say it makes sense, though. ↩ -

Markdown supports HTML comments. They begin with

<!--and end with-->. I use them heavily. ↩