Use a Short Knowledge Cycle to Keep Your Cool

It’s important to manage working time. Managing to-do lists is just one part of the equation to getting things done when it comes to immersive creative work where we need to make progress for a long time to complete the project. To ensure we make steady progress, we need to stay on track and handle interruptions and breaks well. A short Knowledge Cycle will help to get a full slice of work done multiple times a day, from research to writing. This will help staying afloat and not drown in tasks.

Split Up Work Into Repeating Tasks

In the past, we already established that using the Zettelkasten will help you learn faster and obtain deeper knowledge: You get practice when you write about what you read and reveal gaps in your understanding. You gain insight and obtain knowledge when you add notes to your archive and connect them to other items in your system. The necessary coverage is taken care of as soon as you work on your reading and note-taking habits.

In the last blog post, I announced that there’s a thing I call Knowledge Cycle, which is composed of these action steps:

- research,

- read,

- take note,

- write.

The ongoing cycle is driven by feedback of the previous ones. It’s a powerful model to use to think about making knowledge work efficient.

The Knowledge Cycle also suits my workflow far better than ticking to-do items off of a list. Creative work requires immersion which tasks management components of systems like Getting Things Done just can’t sufficiently take care of. Of course we need to manage tasks, but next to that, we need to manage time efficiently to make continuous progress.

Progress is continuous when we are certain we move forward. This implies we complete one chunk of work after another. The opposite would be to research for days, not knowing where the research leads us. We’re busy when we research, but we have to asks: are we moving towards the goal? We wouldn’t know until we try to integrate the new findings into what we already have, be it a draft or just a pile of notes. Continuous progress is about constant re-affirmation that we’re on track. Consequently, it’s about short Knowledge Cycles, because a short Knowledge Cycle implies moving from research to writing in a short amount of time, repeatedly.

There’s resistance in us to this approach. It’s hard to split important work into chunks of time because to split means to stop. That usually feels weird. Switching gears feels like a waste of time indeed. We don’t like to stop what we’re doing because we want to move faster and not halt. Interrupting the research process for taking notes will slow us down, won’t it?

I think this is wrong. It’s wrong because the brain makes use of breaks to clean up the mess and solidify knowledge. We have to take breaks from all work and move for a few minutes. We also need to switch tasks to get another view of the matter. Of course we need to ensure that we can pick up work where we left if need be. But switching from research to note-taking may show that the current trail of literature isn’t leading anywhere important – a finding we would have missed if we kept immersed in skimming texts and finding additional material.

Research is addictive, because it rewards us with the false impression of making progress. Finding something interesting isn’t the same as knowing something and being able to work with it. I call this the Collector’s Fallacy.

I know the anxiety to leave my work place when I’m programming: “I’m so into this problem and I know I can solve it pretty soon! Just five more minutes, I need just five more minutes. No need to take a break now. I’ll take it afterwards.” Whenever this happens, I mostly achieve … back pain. From sitting too long at a stretch. But I don’t realize it sometimes. That’s what break timers are good for. Sometimes I think I’d have dropped dead already if I hadn’t discovered an app which interrupts my work every 20 minutes.

Now I know from experience that I can take a short break and come back refreshed. I don’t even lose the context. I don’t need the proverbial fifteen minutes to get into the flow again and to wrap my head around the task I left. I think this is because I didn’t really mentally leave it during the 2 minute-break I just took. I still thought about it. I simply got out of the mess for a little while.

I won’t write much more about breaks today. To get the most out of short Knowledge Cycles, though, I think you should try a work-to-break ratio of 20 minutes/2 minutes. Then take a longer break after about three of these intervals. For me, it changed everything. I can anticipate how much I’m able to achieve in each of these intervals (or ‘pomodoros’, if you like). I am no longer afraid of putting my tools down for a minute, because I experienced that my work gets better and not worse when I stop.

I am confident in switching tasks and taking breaks, and I think this is a key ability to do any meaningful work. Try this for yourself for a couple of days to find the relaxing freedom in being able to take breaks with confidence.

This ability enables us to redesign how we work. I already said that Knowledge Cycles should be short, and that you, consequently, better have many of them. Let’s talk about how this works.

To Make a Habit of Learning

The Knowledge Cycle is composed of these steps:

- Research for new material, where we have to scan and select what’s useful and what isn’t,

- Reading the findings, thus increasing our temporary understanding based on the capacity of our short-term memory,

- Taking lasting notes to feed the Zettelkasten and thus permanently increase our knowledge.

- Compose a new section or add notes to the outline of an existing draft.

Usually, we think about writing projects as a whole to be made up of these four parts. First, do some research, and in the end you finish writing the text. Most of the time, the process isn’t perfectly linear, but it seems to suffice to separate the tasks and continuously move forward.

Instead, work iteratively. Research for a while, then read and take notes, then write something in your draft. This is like continuous integration in software development: as long as you get feedback quickly, you won’t be surprised by parts not fitting together. The opposite would be “Big Bang” integration: you develop all the parts in sequence or in parallel and hope for the best, that is that they fit together nicely. Most of the time, the parts won’t fit. That’s why “Big Bang” integration has such a bad reputation. It’s the same with writing projects. If you work on the final draft continuously, you’ll know how well your past efforts fit into the bigger picture.

The bottom line is, you can’t fool yourself anymore into believing everything and anything may be useful in the end. Some things are just a waste of time. Because you work on the final text all the time, you’ll know when otherwise rewarding activities won’t help you move forward. You’ll have a clear vision of your project, constantly.

It’s useful to keep the knowledge cycle short. The shorter it is, the better you can judge what’s useful in the following round. We pick material based on our actual knowledge, and from increasing our domain knowledge follows that we get better at picking new material. You minimize waste by making informed decisions – waste of time and energy, that is.

Most writing projects with sufficient complexity are completed iteratively anyway. We form thoughts when we write. These thoughts are important for planning and making better decisions. That’s why I call it a cycle of knowledge, not a cycle of getting writing projects done: ultimately, everything we do in a writing project is about increasing our knowledge during the process and teaching the results with our writing. Consequently, it’s rational you start writing early so you’re able to improve your ability to think about the topic and make more informed decisions.

You will go through lots of these Knowledge Cycles until your project is finished. That’s why it’s called ‘iterative writing.’ This iterative approach may feel weird at first, but it’s the same uneasiness we feel when we’re about to make breaks from work: we are afraid we miss something if we don’t continue and immerse even deeper in what we do at the moment.

It might help to establish a way to leave instruction for your future self so picking up where you left off becomes a no-brainer.

Getting past this limiting belief that changing activities from research to taking notes, for example, will decrease your productivity will pay off manyfold. It pays off because you can be more relaxed about the overall project: you just know that you’ll be able to pick up work where you left off, and you will be content that you achieve something substantial every day, from the first day on. This confidence comes from drafting early, and drafting often.1

Keeping the cycle short also helps to avoid trapping into the Collector’s Fallacy, which basically states that when we own a text, be it on paper or PDF, we tend to think we ‘have’ the knowledge it contains. * We need to make the knowledge our own, though, and work with the text. This includes taking lasting notes. Instead of researching for a while and amassing potentially relevant texts, you process the findings early. This way, you won’t get overwhelmed in research findings.

Part of the usual anxiety of larger writing projects is due to the insurmountable pile of work yet do be done, compared to the measly amount of text you have written by that time. Don’t put yourself into a low-power position like this. Tackle problems early on to overcome the pressure. This implies writing your first line of text on day one, and never stop doing so.

Most of us alternate between the various tasks anyway. But to avoid the common traps like feeling powerless in face of an insanely long list of research findings, we need to raise our conscience about the process. It helps being able to reason about the process and look for ways to optimize the flow. It’s also useful to make a good routine of it.

How to Create a Routine of Short Knowledge Cycles

To form any habit, we need to find and stick to actionable goals and boundaries and keep record of our progress. We can apply this to maintaining short Knowledge Cycles easily. I already sketched this in my post on the Collector’s Fallacy, but here you find a more recent version.

The process of adaptation goes like this:

- Start with 1 hour of research. Stick to the time limit. You will return to this later, so take note of your trails before you leave.

- Process all your findings of the first step. Take notes and connect them in your Zettelkasten note archive. Once you think you got everything in the archive, add the notes or references to them to your draft. Write a sentence or two to explain the connections between the notes you just inserted if you like. Do whatever it takes to really integrate the new findings into your current draft.

- Reflect on the process. How well did you do? Did you learn something new? Judge the processing work you had to do: Was the amount of material manageable? How long did it take to work through your findings Would you prefer to have more or less time to research? Keep book of your answers. It’s important to write them down in a log to review changes over time.

- Adapt the routine: change the time limit of your research. Try to double or halve the time at first to get a feeling for the direction in which you’ll have to push the time boundary. The time it takes to process your findings is part of the feedback you can use to change the boundary.

Repeat the process.

Maybe you start with 1h of research, then try 2h and still feel comfortable, try 4h but have the feeling it’s too much, aim for the middle of the last ones, 3h, and end up with maybe 2h30min as your personal preference.

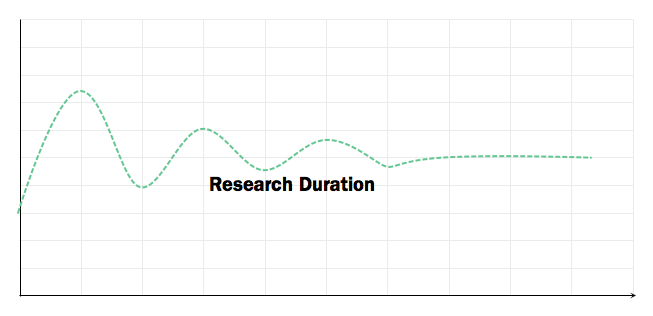

After some time, you obtain relative expertise in your field. To know more means you can deal with more detailed problems. Since details are harder to tackle, you’re probably going to decrease the allotted research time in favor of keeping processing the material manageable.

With time and experience, you’ll know how much research you can handle at the start of a project and how to adapt your schedule. You’ll be able to plan writing projects better than most of your peers.

If you don’t need to do research because, say, you have to write about one large book only, you have to change the process a bit. You won’t need to regulate research time, but reading time instead. You can limit time spent reading or the amount of pages read each session. You can also alternate between modes of reading with each cycle. There are four levels of reading Adler and van Doren recognize in their classic How to Read a Book.2 For example, you can skim the whole book first and take notes on your overall feeling for the topic. Later, you can skim sections and compare them. Sometimes, you’ll read a few pages with great effort. The one thing to keep in mind is this: know in advance when you’ll have to stop.

Keep in mind that our memories aren’t reliable, so don’t try to work with it alone. You’ll need to keep a log and take a look at it whenever you want to change the process to make an informed and directed change instead of blindly guessing what could work next. Reflecting on the process will inevitably give your mind a bit of rest. This might trigger ideas which lead you to research differently and get new insights. So take the logging and journalling seriously.

Conclusion

So I hope you take regular work breaks to stay sane. As a side-effect of learning to take short breaks regularly, you will lose the anxiety that stopping what you do will make you less productive. Because our minds need to rest a bit to operate on a high level, taking breaks will make you more productive instead.

Once you know you can get back to work whenever you want to and continue where you left off, you’re free to alternate the kind of work you do. There’s no need to “Research All the Things!” en bloc, just as there’s no need to complete any tasks without interruption. To alternate activities can be useful because our brains can figure out missing pieces in between without us knowing.

Get rid of the anxiety, and work to lose the limiting belief which says you have to complete something in one sitting. I think the finding by Jason B. Jones sums it up nicely:

There’s a reason there are books like Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day, but not any called Writing Your Dissertation in a Single Caffeine- and Adderall-Fueled Week.

Apart from being a less stressful and thus healthier way to tackle writing projects, to alternate writing-related activities can boost your productivity. When you write early and write often, you will be able to think about the problem domain with greater expertise. Writing improves thinking, and thus it also improves making project-related decisions, like which resource may be useful to look at next during research.

Therefore, you should aim to keep the Knowledge Cycle of research, reading, taking notes, and composing short.

Tell me how it works for you!

-

“Release early, release often” is a programming paradigm which ensures we software developers get feedback quickly. The benefits are the same when it comes to writing: the sooner you start to make sense of the stuff you found, the sooner you’ll know whether you’re heading in a good direction. ↩

-

Affiliate link. You buy from this link, and I get a small kickback from amazon. No additional cost for you. ↩