Three Layers of Evidence

In a Zettelkasten – if done correctly – there will emerge layers of evidence. These layers represent the necessary processing steps from data to knowledge. It is very rare that raw data is put into the archive. You can do it. But normally, you will process the data outside your archive. So I will ignore this possibility. The three layers are:

- Data description and patterns.

- Interpretation of descriptions and patterns.

- Synthesis of patterns, descriptions and interpretation.

First Layer: Patterns

The first layer of evidence is a description of data. I will call that the phenomenological layer. This description is limited to meaningful patterns in the data – or a meaningful lack of patterns, which could be considered as a pattern in itself. If you read an empirical study, for example, you come up with patterns that you can observe and the conditions on which the patterns can be observed.

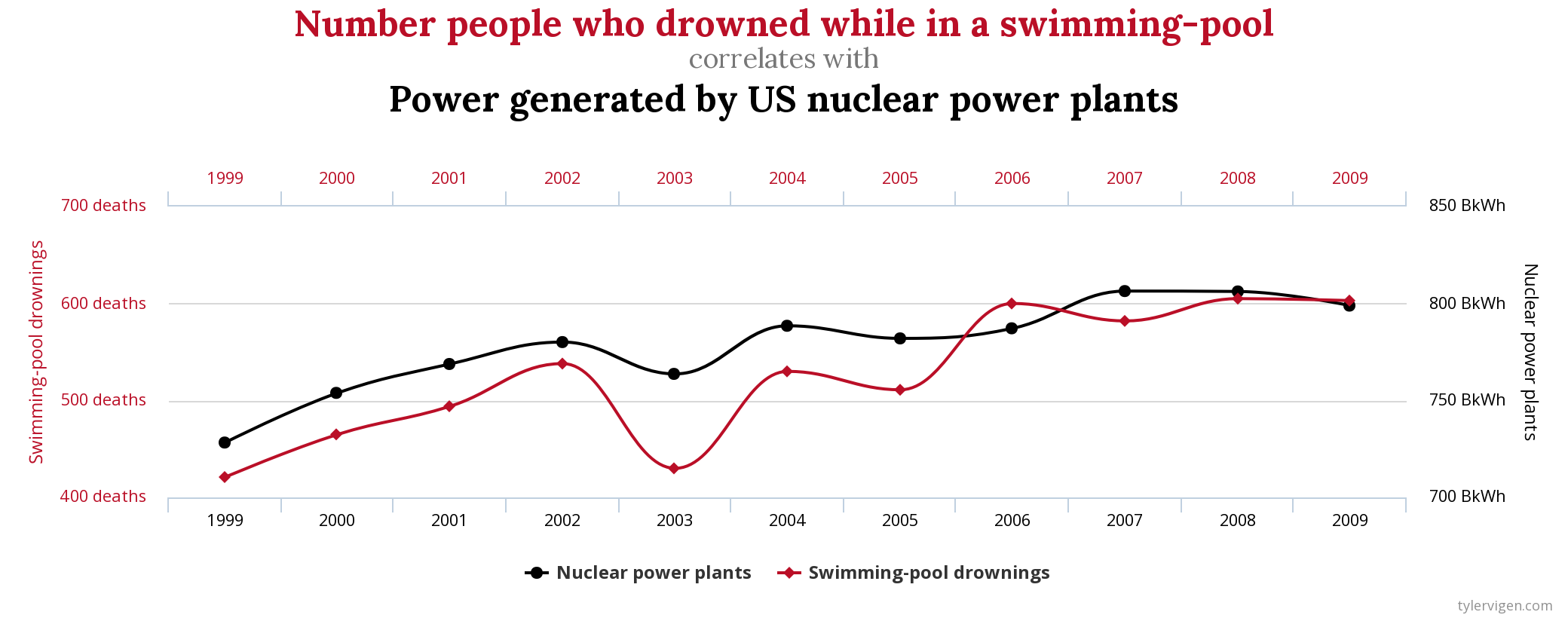

The most common example is a correlation between two variables. An example is the very strong 0.9 correlation of people who drown while in a swimming-pool and the power output of US nuclear power plants between 1999 and 2009:

Correlation has very little to do with causality. Even a correlation as high as in the example above means nothing. It is just a quantified pattern. In this case, the observation of the pattern is as follows: with a positive correlation (pattern: If more then more, if less then less) of 0.9 (quantified value of the pattern) the power generated by US nuclear power plants changed at the same time people drowning in a swimming-pool changed. Correlation is a pattern extracted from data or a pattern imposed on the data, depending on the epistemological dogma you follow.1 Either way, you only have data and patterns.

Second Layer: Interpretation

The next layer of evidence is the interpretation of data patterns. The phenomenological layer meant you describe what you saw. Here, you interpret why you saw it.

Now the concept of causality can come into play. You can explain the correlation above by saying: Drowning people in swimming pools generates amplifiers for the nuclear power plants in the U.S, and that’s why when more people drown in swimming pools, more energy is generated in nuclear power plants.

This layer often breaks and needs regular maintenance. In the words of Nassim Taleb:

Theories are superfragile; they come and go, then come and go, then come and go again; phenomenologies stay, and I can’t believe people don’t realise that phenomenology is “robust” and usable, and theories, while overhyped, are unreliable for decision making – outside physics.2

I don’t go as far as Taleb in saying that theories are unreliable,3 yet in practice it proves to be true . The explanation for correlation above is ridiculous. But it appears ridiculous only because we operate in a field of many knowns and don’t need to scrutinize the explanation. If we operate in the field of the unknown, though, or worse: in field of unknown unknowns, it is very likely that we come up with theories that in hindsight will look ridiculous, too.

A very common mistake I have made a lot of times is ignoring the difference between those two layers. I processed empirical studies but then mainly wrote zettels in the layer of interpretation. This was not a problem as long as I could remember the individual studies. But with time I couldn’t recall the conditions of the studies any longer and wasn’t confident in using those notes. Nowadays, I always write down what the actual study design was.

Example: When I did research on the effects of the low carb diet on blood cholesterol, I didn’t consider the effects of the calorie content of the tested diets. So I had to go back to the studies and filter them for the calories tested. For you non-dieters: If you have a high cholesterol and you lower the calories and lose weight, your cholesterol comes down – no matter which diet you followed before the study. But that doesn’t mean that you just have to control for the calorie content between the tested groups. You have to decide if you test a high calorie or a low calorie diet (caloric surplus or deficit). You have to decide if you have a high or low g-flux (high = train a lot, eat a lot; low = train less, eat less). And you have to decide what you test. If you instruct the participants to eat a certain diet, you don’t test the diet but the instructions of the diet. And so on and so forth … You need to be meticulous with processing studies on nutrition. It pays off a lot if you note what the researchers actually did. :)

Another Example: Very few journalists have the ability to understand science (or humanities, or anything at all sometimes). If you read an article written by a journalist you can be sure that it barely scratched the second layer. My advice: Don’t consume this kind of media at all if you want to be informed on facts instead of opinion. (Most documentaries are just propaganda!) Even though this problem with media seems to be a very recent development, it is as old as mass media itself.4 A journalist who did an excellent job is Johann Hari in his book Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression – and the Unexpected Solutions.

Last Example: If you read a book, you mostly read secondary literature. That means that you read a text that is about texts. Scientific reviews, self-help literature, history books, you name it. Most of what we read is second-hand knowledge. In the beginning of my Zettelkasten work I once read all the studies mentioned in footnotes of a book on nutrition that was famous back then. I was quite surprised at the bias and flawed approaches of the authors. So I pledged myself I would never rely on someone else’s interpretation of phenomena. (See first example.) To this day, I am happy with that pledge and its consequences. It takes some time to process a book, but with the barbell method of reading I am happy with my productivity.

Third Layer: Synthesis

The third and last layer of evidence is the level of synthesis. This layer is to the second what the second is to the first. You take the entities as building blocks for the bigger picture. You string together hypothesis, theories, models and more create something that is useful, interesting, entertaining and what not.

Christian pointed out that this section is suspiciously short. That is because this layer is on the edge between your Zettelkasten and your writing environment. We are about to leave knowledge work and approach writing. I want to focus on the former.

Further Examples

Here are examples of my own work for illustration.

In Fiction Writing

- Phenomenon: There is an increasing number of sex doll brothels that open around the world.

- Theory/Interpretation: The interaction between the relatively free market and the modern hedonistic materialism generates products and services that aim for profit by maximizing hedonistic pleasures for as many people as possible.

- Entertaining/Speculations: I created a cyberpunk world that explores the consequences of a world in which sex doll brothels are the norm, no natural food exists, no physical labor is necessary etc. Then through characters with different backgrounds I explored if one can, would, or even has to rebel against the tyranny of comfort and lack of challenge.

In Health and Fitness

- Phenomenon: One study showed that some training can increase the relation of fat to carbohydrate you use for up to 24 hours.5 Another study showed that in overweight people, fasted training in the morning results in a ad libitum reduction of calories reduction of carbohydrates.6

- Interpretation: There is an acute effect on the metabolic flexibility that is distinct from the general metabolic flexibility one has and that is used as a model in current science.

- Tool: You could do very brief and intensive exercise before your breakfast: One set to failure of each exercise: pushup, rowing in rings and squats. After that you do a maximum one-minute-sprint on an ergometer-bike. That will increases you ability to stay away from carbs and should reduce your cravings.

In Psychology

- Phenomenon: Serotonin is part of the physiological substance that constitutes status.7 Cooperations and alliances are integral part of status.8

- Interpretation: Serotonin is a regulator of negative emotion and emotion in general can be optimized via dominance and cooperation.

- The broader picture: You cannot have optimized serotonin while being weak (lack of dominance) or being alone and only dominant (lack of altruistic behavior). Depression as a side effect of deregulated serotonin can only be considered a physiological disorder if there is no disorder in the rest of one’s life, like being isolated or lacking competitiveness. Therefore, self-development depends partly on the correct (factually and morally) application of status principles in your life. Computer game addiction is an example of pathology and developing your (creative knowledge work) business to support your loved ones is an example of healthy behavior.

In Business

- Phenomenon: Feature Requests are truly that. Users normally express their wishes in the form of a specific app behavior. E.g.: The Archive should allow for multiple tabs. The Archive should allow for multiple windows.

- Interpretation: Feature Requests depend on the individual representation of the problem. They are the concrete manifestation of more abstract problem. User say “I want multiple tabs and multiple windows!” rather than “I have difficulty to handle complex projects with a lot of notes and layers. I think that multiple tabs and windows would help me.”

- Practical Application: Ask for the specific use cases. Ask for the perceived problem and try to get the actual problem and not the individual representation of the problem that manifests in a specific feature request. You can decide which steps you need to take much better once you understand the problem in this context.

What Can You Do to Improve How You Deal With Those Layers?

That was a lot of theory and examples. Let’s dive into some of the practical implications for creative knowledge work.

1. Divide those layers

Your notes should always reflect those different layers of evidence. They build on each other, not only in an abstract way. Either a note belongs to one of the layers, or it itself is divided according to those three layers. In the first case, it only contains phenomena, interpretations, or integrations. The notes are then linked to each other: An interpretation note links to a phenomenon note as reference, the integration notes link to the interpretation notes. In the second case, the note contains a description of phenomena at the top, followed up with the interpretation of the phenomena and the integration into the bigger picture.

It is not always possible to be that clean. But take it as an ideal to strive for. It is also a tool for thinking which is not an incidence. The Zettelkasten Method is the concrete manifestation of the abstract principles of good thinking practices and knowledge creation.

2. Read and learn with those layers in mind

The principle of layered evidence is either correctly applied or violated. You can read and learn from both. Sometimes, authors don’t care if they reference secondary or primary literature. If you want to work correctly, you’ll have to deal with this behavior. If you read something interesting but the facts are not derived from primary literature, you can’t trust those facts. Always – at least at random – check if the primary literature is used correctly. I fell flat on my face after I first discovered how widespread mishandled and misused primary resources are. There are a lot of people who want to sound scientific as a means of marketing.

So, always check the primary literature if there is any. Take texts that cite only secondary literature with a great heap of salt.

Christian’s Comment: One of my first real Zettelkasten projects was in 2009, at University, when I read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. I didn’t understand a lot. The language was weird, it took ages to extract any meaning at all, and it was an overall cumbersome undertaking. (Funnily, nowadays my brain seems to have adapted to more complex literature and weird sentence structures and I can read similar texts quicker.) Still, I found parts to be inspiring, thought-provoking, or irritating. I often could not pin down what was going on in my head and why a sentence struck me as relevant. So I ended up re-stating what Kant said in my own words, but not really: I just rephrased what I thought he wrote, but since my understanding was sub-par, I could not get creative and summarize the content properly. I was also afraid to lose information in the process. Sascha’s post and separation of layers reminds me of my struggle and I think that I could’ve used this approach for non-empirical reading of Kant as well: (1) What does Kant say, quoted? (2) What do I think does this mean? Why is it interesting? How does secondary literature interpret the part? (3) … well, there’s not much practical application of Pure Reason, besides beginning to think differently about the universe and everything of course.

-

There is an eternal debate on the nature of knowledge and information between constructivists and realists positions. The constructivists believe that patterns are imposed and realists believe that they are extracted. ↩

-

Nassim Nicholas Taleb (2012): Antifragile. Things that Gain from Disorder, St. Ives: Penguin Books, p. 116. ↩

-

To be fair to the author. It is totally possible that he was a bit hyperbolic. ↩

-

Tim Wu (2016): The Attention Merchants. The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Out Heads, New York: Vintage. ↩

-

A Z Jamurtas, Y Koutedakis, V Paschalis, T Tofas, C Yfanti, A Tsiokanos, G Koukoulis, D Kouretas, and D Loupos (2004): The effects of a single bout of exercise on resting energy expenditure and respiratory exchange ratio, Eur J Appl Physiol 4-5, 2004, Vol. 92, S. 393-8. ↩

-

Z. Alizadeh, S. Younespour, M. Rajabian Tabesh, and S. Haghravan (2017): Comparison between the effect of 6 weeks of morning or evening aerobic exercise on appetite and anthropometric indices: a randomized controlled trial, Clinical Obesity 3, 2017, Vol. 7, S. 157-165. ↩

-

E A Kravitz (2000): Serotonin and aggression: insights gained from a lobster model system and speculations on the role of amine neurons in a complex behavior, J Comp Physiol A 3, 2000, Vol. 186, S. 221-38. Robert Huber, Kalim Smith, Antonia Delago, Karin Isaksson, and Edward A. Kravitz (1997): Serotonin and aggressive motivation in crustaceans: Altering the decision to retreat, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 11, 1997, Vol. 94, S. 5939–5942. MJ Raleigh, MT McGuire, GL Brammer, and A Yuwiler (1984): Social and environmental influences on blood serotonin concentrations in monkeys, Archives of General Psychiatry 4, 1984, Vol. 41, S. 405-410. Wai S. Tse and Alyson J. Bond (2002): Serotonergic intervention affects both social dominance and affiliative behaviour, Psychopharmacology 3, 2002, Vol. 161, S. 324–330. Ania Ziomkiewicz-Wichary (2016): Serotonin and Dominance, Cham: Springer International Publishing. ↩

-

Joey T Cheng, Jessica L Tracy, Tom Foulsham, Alan Kingstone, and Joseph Henrich (2013): Two ways to the top: evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence, J Pers Soc Psychol 1, 2013, Vol. 104, S. 103-25. Kimberly G Duffy, Richard W Wrangham, and Joan B Silk (2007): Male chimpanzees exchange political support for mating opportunities, Curr Biol 15, 2007, Vol. 17, S. R586-7. Jaak Panksepp and William W. Beatty (1980): Social deprivation and play in rats, Behavioral and Neural Biology 2, 1980, Vol. 30, S. 197 - 206. ↩