Create a Zettelkasten for your Notes to Improve Thinking and Writing

- Who is this for?

- People who want to improve their writing and coherent thinking,

who are invested in so-called knowledge work and who connect ideas.

This suits academics, authors and writers, journalists, but also programmers who organize their knowledge.

Assuming you’re a writer or a thinker, why should you care about the way you take notes? If you want to think creatively and write original articles and books, you need to form associations in your mind effectively. Notes can help you with that if you adhere to a few basic principles.

You can emulate communication processes with your own notes if you structure them in a certain manner. Notes can and should stimulate new associations and foster your creativity just like a good talk does.

Inspired by Scholarly Techniques

Enter the Zettelkasten.

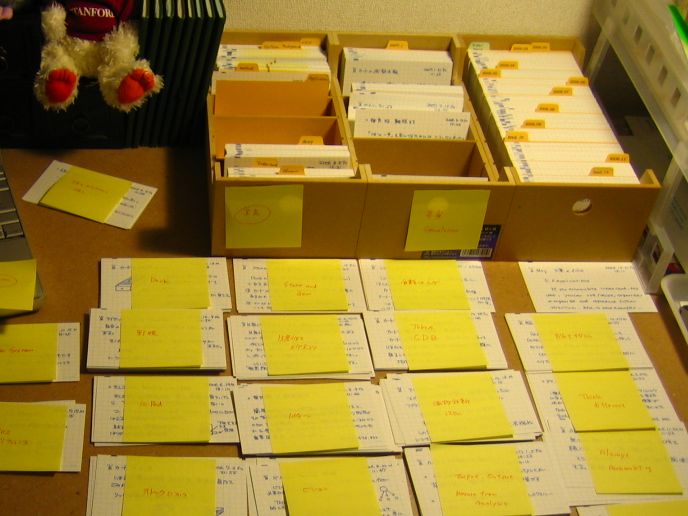

There’s a scholarly technique to organize personal knowledge that has been known about for ages. On paper, it works with index cards onto which you write citations and notes. This is basic input/output-style information recording. Think personal wiki. A suitable metaphor is “extended mind” or “secondary memory”.

Storing stuff in small-ish notes is the fundamental principle in creating a device called “Zettelkasten” (German for “slip box”, or “card index”). Vladimir Nabokov, Jean Paul and Arno Schmidt wrote their novels’ drafts on index cards.1 German sociologist Niklas Luhmann’s productivity was increased to epic proportions (70 books, 400 articles) with the help of his Zettelkasten.2

Doing it right, you can move way beyond input/output-based note-taking. You can interact with and communicate with your system of notes. As holds true for every communication, you’ll learn something new when you interact with your Zettelkasten. Here I’ll show you how that’s possible.

The principles I lay out in this post apply to both digital and paper-based notes. The distinction between the two doesn’t matter, yet. In upcoming posts on this topic, I’ll show you a digital note taking approach which adheres to these principles.

Let’s start with the thought before we get to the note.

Improve Thinking by Writing: Why You Should Take Notes [impthink]

Whenever you want to think to some purpose, you should consider writing it down. See Luhmann, Communication with Slip Boxes. An Empirical Account, and the book by Steffens (pp 20–21, see references).

- Writing improves your ability to think coherently: “what’s my point?” Whatever the answer, you’ll be able to stick to it.

- Writing prevents you from jumping around in your mind, forgetting details, but rather to think consistently: “how is my point being developed?”

- Writing things down improves memorization.

- Thoughts written down can be retrieved as-is. This conquers hindsight bias which makes you change your mind after the fact, pretending you knew it all along.

Writing clarifies your thinking. Thoughts and feelings are nebulous

happenings in our mind holes, but writing forces us to crystalize those

thoughts and put them in a logical order.

—Leo Babauta at Zenhabits

So you really should write down what you think if you want to improve your thinking.3

But chances are you already do take notes.

So here’s the next step: if you take notes and write a lot, it’s only rational to do it in a way that trains your system of notes to become a partner in communication with you.

Create Notes to Converse With

That’s right: you should be able to communicate with your system of notes. Your system will respond to your queries in a meaningful manner to which you both can relate. You ask, your notes answer. Ideally, both learn.

I’ll show what generally enables a thing (or person) to communicate with you before we see how you teach your notes to communicate.

Criteria to improve your notes

You usually retrieve notes from a bucket of some sort. To say that there’s communication happening, you have to move beyond basic input/output retrieval.

Boiled down, the basic needs of a communication system according to Luhmann in Communication with Slip Boxes are as follows:

-

Irritation: basically, without surprise or disappointment there’s no information. Both partners have to be surprised in some way to say communication takes place.

Stated simply, “surprise” means you stumble upon notes which you hadn’t expected. Your system of notes, on the other hand, receives a new note from you which wasn’t there before. (It’s properly called “serendipity”.)

-

Information: the informativeness of the communication depends first on your expectations and second that both partners use some comparative measure to see if their expectations are met.

In other words: you should notice that you did find a thing and that this thing is a note which you ideally didn’t even expect to show up.

-

Complexity: your partner needs to be sufficiently autonomous. Autonomy is promoted by growing inner complexity of the system. Its inner complexity depends on both the number of notes and their relationships with each other.

Therefore your system of notes should become larger to increase the system’s number of elements, and notes should reference one another to increase the system’s number of its elements’ relations.

This works with both digital and paper-based notes. Fundamentally, when you let notes point to each other using some kind of reference, you’re creating hypertext. This concept is well known on the web where hypertext is presented as links you can click on in your browser.

On paper, you could write “see”, “cf.” or draw an arrow before you reference a note by number, arbitrary index, its title or whatever. You’d still have to pick up the referenced note by hand if you’re interested in its content. Still, the concept is identical to implementations of hyperlinks in a document on your computer or in its file system, where there are file aliases, hard links and symbolic links.

These criteria – surprise serendipity, information and inner complexity4 – are the criteria any communication has to meet. And your system of notes, your Zettelkasten can meet them just as well as a human being.

So how do you ensure you establish a communication system with your Zettelkasten?

Loose Filing and Interconnectedness are Key

In a nutshell, you’ll have to store lots of interconnected notes and forget what you put in to be surprised by the results of your search queries. There’s a certain way to store notes which facilitates organic growth and hypertext.

-

Do not sort your stuff. Don’t waste time making up categories; this hampers organic growth.

Also, you won’t know what you’re going to take notes on when you begin. Maybe your interests will shift. Or you’re going to specialize in a field which is way down any usual hierarchy but will be of subjective importance to you.

This bucket’s for you and for you alone. It’s your idiosyncratic partner in knowledge work. Your second brain. Your extended memory and your better self. Don’t put it in chains imposed by others. Things aren’t important simply because of their topic but because you write a lot about them. Naturally, topic clusters will turn up.

-

Identification. Every note should have an ID. It suffices to count the notes. If you need to put a note between two adjacent notes, increase the level you count on. Between “57” and “58”, there’s room for “57a”, “57b” and “57a/5g92”.

Of course, digital note taking makes putting new notes between existing ones obsolete. You can edit text files to your liking and won’t need to branch off. Hypertext can cope with all the other issues.

-

Connect. There’s two ways to connect notes: let them point to each other directly or form keyword-based collections.

- Hypertext. Link to notes by ID to create a hypertextual system of notes. This is direct connection.

- Keywords. You need to find something specific in your 10,000 notes? Attach keywords or tags to notes to add a second retrieval mechanism. An index of keywords forms an indirect connection between various notes via generalization to a keyword: they don’t know each other, but they’re similar in some respect. Utilizing full-text search, you won’t need to keep track of keywords and notes in an index, though.

When you get used to heavily linking notes, your workflow will change. And so will your system of notes evolve into a Zettelkasten.

Update 2015-11-04: See my post on weak and strong ties for further discussion of connections.

Conclusion and Implementation

By now you should understand what it means to create a device to communicate with: plan to be surprised and design the process accordingly. Hypertext makes this possible, and full-text search should even make you faster than Luhmann, whose 20,000+ notes were stored on paper.

It’s meaningful to say you communicate with your notes. But to get there your system of notes has to adhere to some rules to become less mute and less stupid.

Model the system according to the most basic functioning of our human brains: nodes won’t work properly in isolation but need to be heavily connected. The more connections there are between our neurons, the easier information can be retrieved and the better we perform a task. So connect your notes. Then let them surprise you.

Next, I’ll show you how to implement a Zettelkasten on your computer. Stay tuned!

Thank you, Hilton, for reading and editing the final draft and for encouraging me to publish it soon.

- Niklas Luhmann (1992): “Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen. Ein Erfahrungsbericht”, in: Universität als Milieu, edited by André Kieserling, Bielefeld: Haux. – Take a look at the full-text translation titled Communication with Slip Boxes. An Empirical Account by Manfred Kuehn.

- Bernard Rimé, Catrin Finkenauer, Olivier Luminet, Emmanuelle Zech, and Pierre Philippot (1998): Social Sharing of Emotion: New Evidence and New Questions, European Review of Social Psychology 9, 1998, Vol. , S. 145–189.

- Henry J. Steffens, Mary Jane Dickerson, and Wolfgang Schmale (2006): “Schreiben um Geschichte zu lernen. Überblick und Einführung”, in Schreib-Guide Geschichte, edited by Wolfgang Schmale, Wien and Köln and Weimar: Böhlau.

-

From Wikipedia I got the info about Nabokov. Jean Paul’s 1796 narration Leben des Quintus Fixlein is subtitled “aus funfzehn Zettelkästen gezogen; nebst einem Mustheil und einigen Jus de tablette” (literally: drawn from fifteen card indexes). Arno Schmidt’s so-called “book” Zettels Traum (roughly “index card’s dream”) looks like the collage it really is. You should just take a look at Zettels Traum and see for yourself! ↩

-

From Luhmann (Communication with Slip Boxes. An Empirical Account) I took the model and the arguments I demonstrate in this post. All credit’s really due to him. His article translates to Communication with Index Card Systems. An Empirical Account or Communication with Slip Boxes. See the English full-text translation. ↩

-

Refer to the research of Rimé et al, _Social Sharing of Emotion (see references) who have found people talk about troubling topics like emotions a lot. Some suggest this is an indicator that talking will clarify your understanding. ↩

-

This approach is based on terms from cybernetics and general systems theory, in case you’re interested in the concepts. ↩