Different Kinds of Ties Between Notes

After the awesome discussion of Sascha’s latest blog post, I meditated about all the different kinds of ties between notes. Here’s what I came up with.

Juxtaposition and Sort Order

When you work with paper, it’s obvious that they have an order – but even digital note archives will put all your notes in some kind of order in the user interface to present them. This is done most likely as a list.

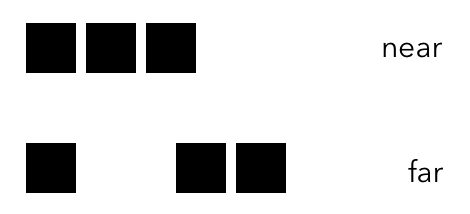

A fundamental principle of composition: things that are near to each other seem to belong together. How they belong together is often imaginative. Our brain sometimes forces a reason upon us which doesn’t make much sense at all.

When you have 1000 notes and your application currently shows a list of 10, say, it’s more likely that you will involuntarily try to find some order in the currently visible chunk. “So here’s a note about Plato. And there’s another. And the next is … huh? About sharpening kitchen knives!?” – The mere (dis)order of things can be an information itself.

So if the position of two notes is an information itself, you’d have 999 extra bits of information in a list of 1000 notes. Naturally, two notes on the same topic carry a different information than one note about Plato and one about knives next to each other.

You can utilize this of course.

Dan Sheffler sorts his notes by title. He also adheres to the convention where the more general term is kept at the beginning. Taken from his post, he has notes called:

- Plato

- Plato – Tripartition

- Plato – Tripartition – Glaucus Passage

- Plato – Personal Unity

- Plato – Self-Mastery

While I’d say that Dan’s naming scheme brings brittle categories back with a vengeance, it’s at least a conscious choice he made. If instead one note was called “Glaucus Passage in Plato is not …”, it would appear next to other notes starting with “G”. Totally different game which increases the randomness of results a lot. Randomness might become a trigger of inspiration, too, of course.

Sascha and I decided to sort notes by ID, which happens to sort them by date in our case, too. (Remember an ID looks like 201511041548, representing 2015-11-04 3:48 p.m.) My initial incentive to do so was a lesson from the Noguchi filing method which acts on the premise that humans tend to remember the date or time of year we did something very well. Probably because humans like stories, so that seemingly arbitrary events like receiving an invoice on March 30th may coincide with the birthday of your mother, say, and thus is “filed away” in a similar box of your episodic memory.

Whatever naming scheme you pick, it’ll influence what your brain automatically does: making sense of items close to each other.

This will become even more important when you actively look at the list of notes. Most of the time you don’t have to pay attention to it I assume. But when you look for something, when you’re in hunting mode, you will look at filtered search results with much more focus than usual. Because now the list is meant to be informative, whereas most of the time you don’t need it and ignore it.

Smarter search applications like DEVONthink can even sort search results by relevance, which is derived from content and tags, for example. Stuff high up in the list is more important. You’d look at the items at the top and try to see if there’s something of interest to you. And your brain will suppose an underlying connection between them. Are you surprised by the result? Maybe you should consider connecting them more closely, voluntarily.

Tags/Keywords

I wrote about this before when I tried to show how a Zettelkasten can extend your mind. There, and in my first post, I have stressed the importance of connections.

A connection or association is a stronger tie than mere juxtaposition. It’s stronger because it is voluntarily. At one point in time, you have decided to connect A and B.

Tags or keywords are the weaker kind of connection. Direct links are strongest.

Keywords are an indirect connection. They essentially decouple related notes from one another: none of my notes about “#banana” has to know about any other note on that topic. Still, they form a set or cluster.

Categories

We don’t do categories here because they are too limiting. They work in a similar way as tags/keywords: they group otherwise unrelated notes. The result is a set of notes with a label. Category sets are exclusive, tag sets may overlap.

Hyperlinks

Conversely, hyperlinks (or just “links”) couple two notes to each other. When you link from A to B, naturally A has to know about B for the link to work: the link is part of A’s content after all. It also holds true that B is coupled to A, though, through the means of back-linking.

Now backlinks don’t have to be something cool your application offers. Every full-text search for B will yield all incoming links to that note as well.

Say I have a note “201511041610 Banana pancake recipes are the devil”. When I search my archive for “201511041610”, this note will pop up – but so will all the links to it since they reference the link target by ID. (Keep in mind that you should choose your identifiers wisely!)

Links connect “A and B”, implying a bi-directional relationship, and not just “A to B”, which means things work in one direction only.

Folgezettel

We’ve discussed this recently. You can translate “Folgezettel” (literally: “subsequent note”) as “note sequence”.

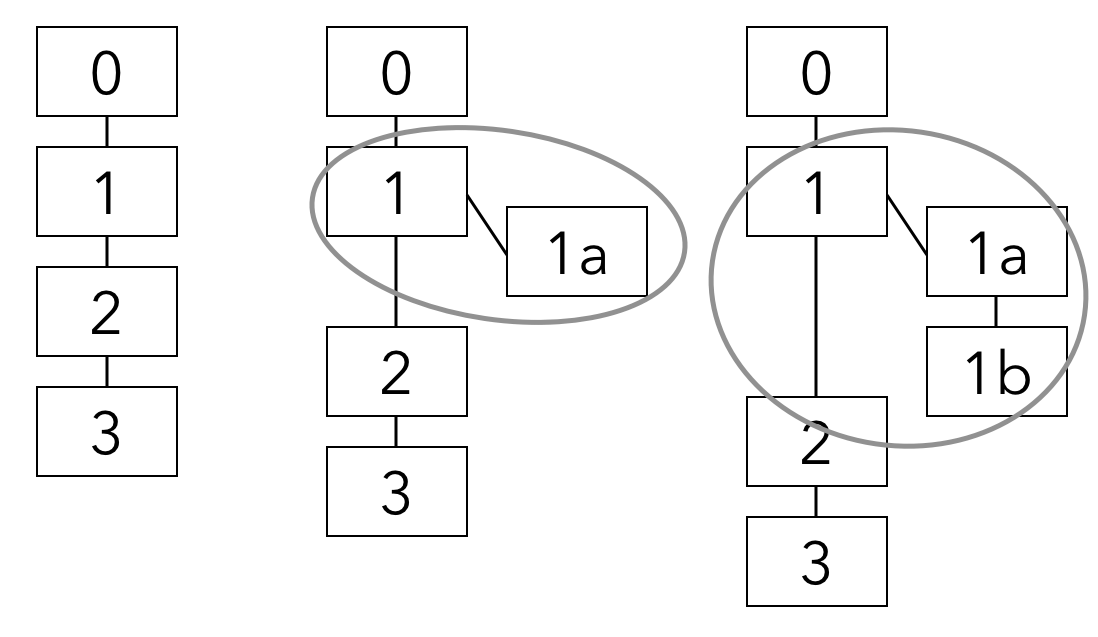

But if you stopped there, you end up with the same concept as juxtaposition. Folgezettel means something different though. The term is meant in a more specific way than it superficially seems. Take a look at the following diagram for clarification:

Most archives don’t support real branches, so Luhmann created branches by changing the alphanumeric ID’s level: after 1, he branched of into 1a, 1b, ….

Even though there’s an underlying tree-like structure, the notes are linearized in the archive. That’s a technical limitation. The notes, in order, are put into this sequence:

011a1b23

Taking “note sequence” or “subsequent notes” literally, everything below 1 in that list is “later in the sequence”, including 2 and 3. But the concept of Folgezettel only implies the child notes, the ones in the sub-branch.

1a is Folgezettel to 1. So is 1b. But 2, for example, is totally unrelated to both of them. It’s neither ancestor nor neighbor.

From the point of view of a single note, every note in its single sub-branch is a Folgezettel. If we continue until 1z and branch off along the way and have, say, 1k7, then these too are Folgezettel of 1.

According to Daniel (PDF link, at pp. 22, 37, & 41), the intention behind all this is to provide a story. We cannot conclude this from Luhmann’s original material, but even if that was his intention, these stories will probably only work when you don’t have a ton of notes. Because eventually the “story” will turn into an epic of thousands of notes, related to the “story” only through their position in the tree.

The problem is that we use a Zettelkasten to dissolve (long) texts and keep short and informational notes around with just the essentials. Our brain can only hold to so much information at a time. When your Folgezettel story turns into an epic, you end up having to solve a problem very similar to reading texts by other people: to grasp the information of the narrative you’ll have to take notes about it. Only this time you take notes about your own the sequence of notes.

With a sort order of branched IDs like above, you could start somewhere and read on and on and on – until the initial note’s ID level is reached. You stop when you reach 2, a sibling to 1.

You see, the principle of using Folgezettel is still quite similar to juxtaposition in general. Folgezettel carry a precise scope: you stop when you reach the sibling of your starting point. Still you utilize the position of the note in the sequence to your advantage and use IDs to create an arbitrary order.

Is that it?

I cannot come up with other kind of ties between notes. It seems this is just it.

Please comment if you recognize additional ties!

Sascha’s Unexpectedly Long Comment: This post points out an important idea of every knowledge management system you use: direct link, Folgezettel, or position in the archive is a connection for later use.

You leave breadcrumbs behind that your future self can follow. You give these breadcrumbs different colors to signify the kind of connection. The coloring of the paths through the landscape of your notes will hint at its structure and difficulty. Some are Folgezettel and some are direct links.

This was the whole point of my last post, “No, Luhmann was not about Folgezettel”. The journey is about the breadcrumbs and not about their color. Pick whatever color you like but be aware that some paths through the landscape are more difficult to cross.

We choose a harsher but shorter route which is the plain text approach. But we have developed the tools to manage harsh terrain pretty well. That means being able to take a shorter route and thus save time and effort since the terrain’s harshness doesn’t matter as you’re using your 4x4 and not a Volvo. :)