How to Increase Knowledge Productivity: Combine the Zettelkasten Method and Building a Second Brain

How to read this article

This article is structured in two parts. First, I summarize the Building a Second Brain (BASB) method by Tiago Forte. Then, I will compare it to the Zettelkasten Method (ZKM). I will first discuss the differences, because they can help to understand BASB and the ZKM more deeply. Then I will explain how to reconcile BASB and the ZKM. Spoiler: they can be combined perfectly.

I have made some changes in my own way of working. I will include these as examples at the end.

The ultimate goal of Building a Second Brain is inner peace

What did Robin Hood feel when he aimed at his own arrow at the center of his target before splitting it? Of all the answers, I like the following the best: oneness with the world with a consciousness that was freed from all its contents. Zen. The perfect inner harmony.

Every form of self-management is an attempt to take a step towards this inner harmony. It is therefore no coincidence that David Allen in Getting Things Done repeatedly points to the goal of “mind like water” throughout his book.1 Forte’s Building a Second Brain builds on the tradition of Getting Things Done. Not only does he write this explicitly.2 It is reflected in advice like this:

Don’t worry about analyzing, interpreting, or categorizing each point to decide whether to highlight it. That is way too taxing and will break the flow of your concentration. Instead, rely on your intuition to tell you when a passage is interesting, counterintuitive, or relevant to your favorite problems or current project.3 (Emphasis mine)

Knowledge work is characterized by the fact that tasks are not given, but must first be recognized as such.4 This lack of clarity about how to understand something and what to do with it leads to psychological entropy. Then, we feel nervous, uncertain, and anxious.5

Any form of self-management is ultimately a method of managing psychological entropy. This is also true for Building a Second Brain.

BASB is a hybrid of (1) information management and (2) project management systems. It is based on GTD and includes customizations for collecting content for projects.

(1) Building a Second Brain is an information management system. Processing of sources is not the focus of the system, nor is the way of processing information an essential part of the system. Even the processing method Forte proposes, the progressive summarization is not a processing method of information, but a preparation method of resources like articles, podcasts, and books for later use. BASB’s strengths lie in the management of sources of knowledge.

While BASB’s “second brain” doesn’t move beyond the resource, the work with the Zettelkasten begins only after we have extracted the ideas and thoughts from the resource and put each of them on an atomic note while leaving behind the resource. This is one of the main differences between BASB and the ZKM. BASB is a system for resource management; ZKM is a method for working with ideas themselves.

(2) Building a Second Brain is a project management system. The emphasis of the whole system on action effectiveness is particularly evident through the filing system PARA.6 The four parts (Projects, Areas, Rresources, Archive) are aligned to a hierarchy of urgency. At the same time, a connection is made between urgency and importance because completed projects are “the blood flow of your Second Brain.”7 Importance and urgency are the categories of projects and tasks. In a sense, the overall system speaks the “language of action”.

In contrast, the Zettelkasten Method speaks the “language of knowledge”. In the Zettelkasten, there is no such thing as importance or urgency. Each note merely contains ideas and their connections to other ideas. Their actionability is a second layer that we put onto them.

Who is Building a Second Brain for?

BASB is for people who want to manage their information streams and resources in a project-oriented way. But probably the most important target group is people who feel overwhelmed by uncertain tasks and modern information overload.

In my experience, there are two main types of overload that can be related to the two components of the temperament characteristic of openness.

- Overload because of Openness to Experience. Formulated as a belief set, the trait Openness to experience would read: What is new is most likely good. Because we live in an age of information inflation,8 we are inundated with newness. People with a high Openness to Experience live in an information land of milk and honey. But people in the Land of Cockaigne are not happy. They are overstuffed and overwhelmed. They don’t know what to do with themselves. And those who don’t know what to do feel anxiety.9 You could compare people with a high Openness to Experience to people who have a particularly strong susceptibility to fast food and sweets. Both tend to engage in erratic behaviour, which in turn can lead to anxiety-generating lifestyles.

- Overload because of Intellect. Formulated as a belief set, the trait intellect would read: Something is interesting if it is a thing that can be studied. These people love to analyze and construct. These are the ones who get lost in analyzing and constructing a perfect system. They run the risk of doing more work on their system than using it for its intended purpose. They can become overwhelmed by a self-created information overload as they build an elaborate system of RSS feeds, web clippers, and other techniques of capturing information and information resources. But they also run the risk of conducting purposeless research, neglecting project- and deadline-oriented work.

BASB can provide the solution for both types of overload:

- It allows managing information and resources with little effort. This helps people who feel overwhelmed with the overabundance of information and resources.

- It is explicitly project-oriented. This helps people who lose sight of project-oriented work because they are so interested in the matter at hand.

How does BASB work?

Disclaimer: If you already are familiar with BASB you can skip by clicking this link.

Like any management system, BASB consists of three components:

- The System. How are the folders, files, inboxes, etc. arranged?

- The Workflow. How do the resources become the desired end result?

- The Habits. What are the regularly recurring actions needed to take to make the system work and be maintained?

Let’s start with the system.

The system - PARA

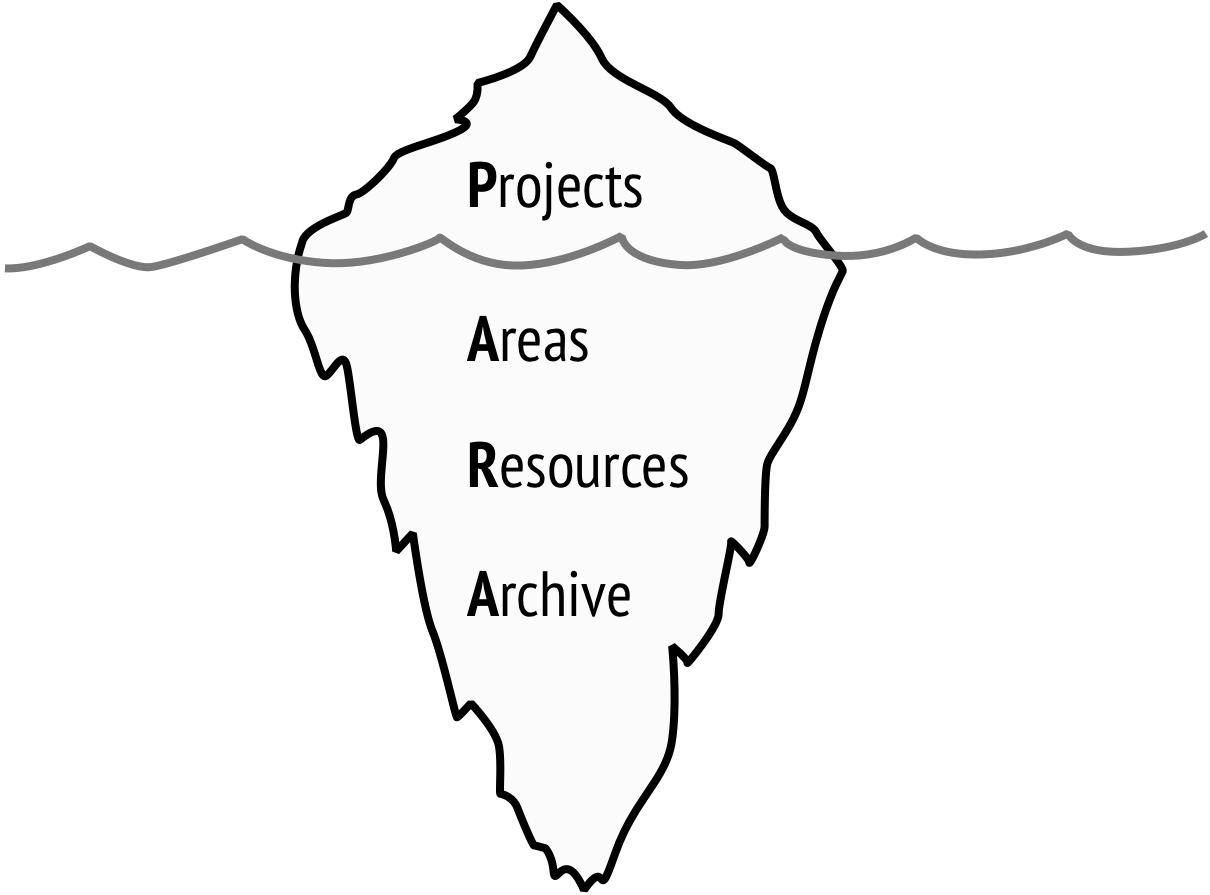

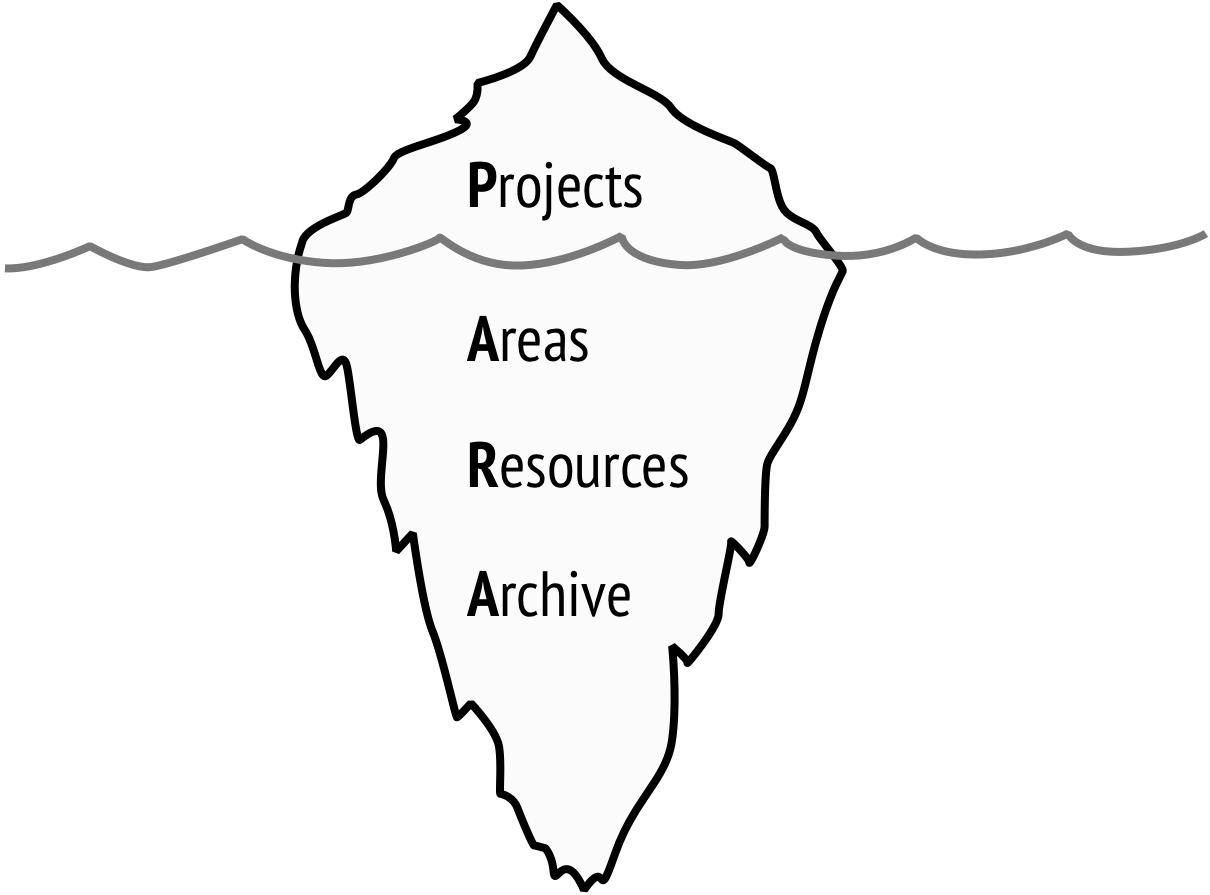

PARA is the storage system of BASB. The acronym stands for the four containers Projects, Areas, Resources and Archive.

In most programs, you’d create a folder for each container. However, in some programs there are no folders. Therefore, I usually speak of “containers”. However, I understand PARA as a manifestation of a general principle of self-organization: the iceberg principle of self-organization. I will describe this in more detail towards the end.

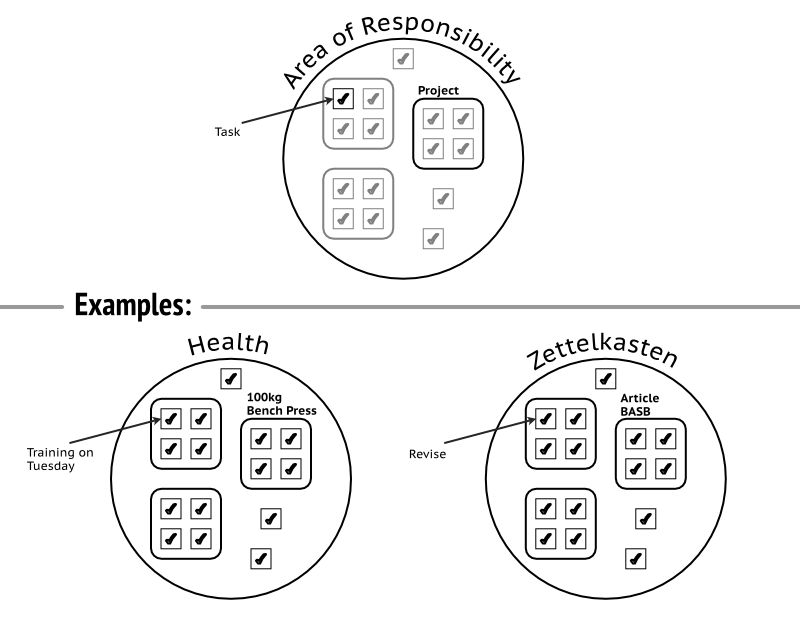

Projects are short-term efforts in work and personal life. They are what you are currently working on.10 They have characteristics conducive to work:

- A beginning and an end (unlike a hobby or an area of responsibility).11

- A concrete result to be achieved and consist of concrete steps that are necessary and together sufficient to achieve that goal.12 Example: Achieve 100 kilos in the bench press.

Areas (of Responsibility) are concerned with anything that you want to keep in mind for the long term. They differ from projects in that you do not pursue a goal with them, but want to maintain a standard. Accordingly, they are not limited in time. One could say that they represent an aspiration on ourselves and our living world.13

Example: Health and Fitness.

Resources are topics that might become relevant or useful at best in the long run.14 They are a catch-all container for everything that is neither a project nor a responsibility. Resources are:15

- topics that are interesting,16

- subjects to be researched,17

- useful information for later use,18

- hobbies.19 (Note: I consider hobbies to be an area of responsibility because hobbies also have standards).

Example: A workout plan to try at some point.

The Archive is for everything inactive from the above three categories.20 It is a storage for things finished and postponed.21

Example: An old training plan.

The four containers are sorted by action relevance:22

- Projects are most relevant to action because you are currently working on them and have a deadline.23 The fact that you have to have a deadline is not the deciding factor, only that you are actively working on them. My personal criterion for this is that I sit down at least once a week to work on the project.

- Areas of responsibility have a longer time horizon and are therefore not immediately relevant for action.24

- Resources become actionable only in specific contexts.25

- Archived stuff is inactive until it is needed.26 Therefore, it is hardly relevant to action.

This four-folder system is kept simple for a reason: Complex systems usually require complex maintenance. PARA abandons this complexity. CODE, BASB’s workflow, is similarly kept simple.

The workflow - CODE

The BASB workflow is divided into four steps:

- Capture includes everything you fill your inboxes with.

- Organise means filing in the PARA folder system.

- Distill means processing of resources with the method of progressive summarizing.

- Express means the application or publication of content.

Forte does give some tips on Capture. However, I do not consider them essential to understanding BASB. Therefore, I will not go into them in detail.

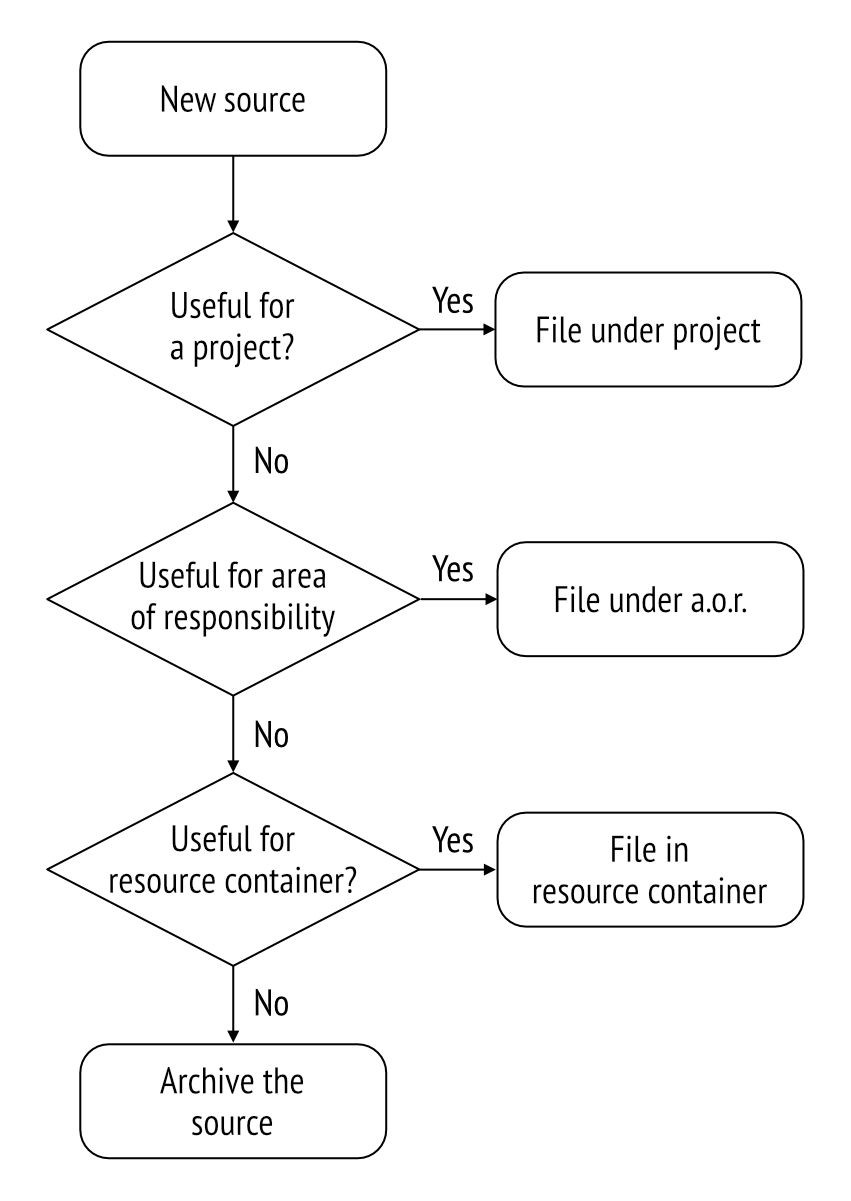

Organize is the step where we empty the inbox and incorporate the resources into the PARA system. In doing so, we use the hierarchical nature of PARA: We first check if the resource can be used for something urgent and then work our way to less urgent:27

- Go through all active projects first. Is the resource useful for the project? If yes, file it under this project.

- If not: Is the resource useful for an area of responsibility? If yes, file it under this area of responsibility

- If not: Is the resource useful as part of a resource container? If yes, file it under the respective resource container.

- If not: Archive the resource.

Distill describes the way the resource is processed. Here, Forte recommends the progressive summary:28

- Acquisition is counted as the first step of processing. That is: the resource is filed. In Forte, this is already achieved at capture. However, I think it is better to assign this step to Organise. Only when we have filed the resource in the PARA system can we speak of a first edit.

- Read the resource and mark in bold the passages that catch our eye.

- Highlight what seems to be extra important from what is already marked in bold.

- The last step would be the executive summary. This means that you list the most important key points of the resource at the beginning of the document.

This is where the difference from the Zettelkasten Method becomes particularly obvious. At no point in CODE do you move beyond the resource inside the system. Only at Express, the next step of CODE, do we leave behind the resource as the unit of information.

With BASB, we get stuck with managing resources because we don’t move beyond the resource. Yet, the method of resource editing is quite easily interchangeable. Even if we process the resource to the point of extracting out each individual thought, as is the case with, let’s say, the Zettelkasten Method, we could still fit the individual thoughts into the PARA system as well. So, progressive summarization is not at all an essential ingredient for BASB to work.

Don’t worry about analyzing, interpreting, or categorizing each point to decide wether to highlight it. That is way too taxing and will break the flow of your concentration. Instead, rely on your intuition to tell you when a passage is interesting, counterintuitive, or relevant to your favorite problems or current project.29

But the progressive summary is in the spirit of a way of working: The progressive summary could almost be seen as a technique for not letting knowledge work distract you from a project-oriented way of working. We will see more about this in the comparison of BASB and the ZKM. Progressive summarization does not involve thorough extracting and processing of ideas.

Express means that Forte encourages us to actually use our system for something. Forte gives some tips in this section such as breaking up larger projects into small steps that are easy to work through.30 But this step is already outside the actual system of processing and management because most likely you will start writing in your dedicated writing app or implement behavioral changes in your life and not in your second brain.

The first three aspects Capture, Organise and Distill concern the input to the system PARA. Express states that we should use the system to its fullest effect. With PARA and CODE, we covered the system and the workflow. Now, let’s continue with the first of the key habits.

The Key Habits

System-relevant habits are actions that are necessary for the effectiveness of the system, and therefore must be done regularly. As with all project and task management systems, there are two types of habits.

- Habits of good use of the system. Through these habits, one derives maximum benefit from the system. In BASB, these are the project checklists.

- Habits of maintenance of the system. By these habits one repairs the current damages and signs of wear. In BASB, these are the reviews.

The Project Checklists

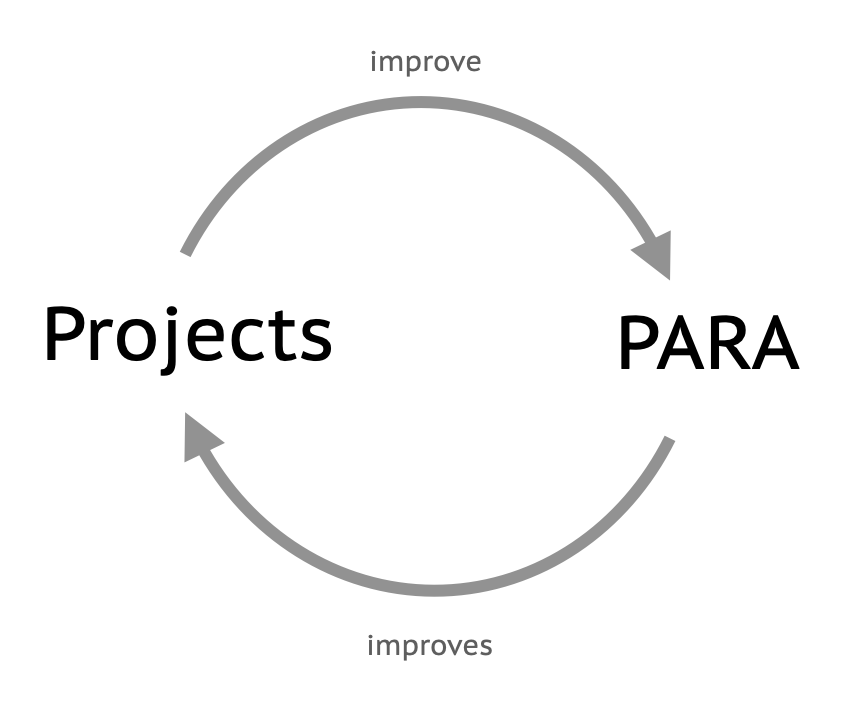

There are two checklists: one at the beginning of the project and the other at the end of the project. The checklist at the beginning of the project is for using the system to its fullest extent for the current project. The checklist at the end of the project is for using the completed project to improve the system.31 So, these two checklists are designed as positive feedback loop:

Checklist: Project Start

- Collect: Gather your thoughts about the project. What do you already know about it? What don’t you know? What is your goal? What people can you tap into? What are possible resources?32

- Review: Search the folders of your second brain for useful information.33

- Search: Use the global search to back up the second step. Sometimes, useful information turns up in surprising places.34

- Move: Move all relevant notes to the project folder.35

- Create: Create an outline from everything you have collected in the project folder.36 Important: You are only planning the project. You’re not working on it directly yet.37

Checklist: End of project

- Mark: Mark the project as complete in your task management and still process any loose ends.38

- Cross out: Mark the goal associated with the project as achieved and move the goal to a “Achieved” list. You can use this list of achieved goals as motivation.39

- Review: Review the project folder for content that you can use for other projects.

- Move: Move the project folder from “Projects” (PARA) to the archive (PARA). 40

- If project is becoming inactive: If you cancel or postpone the project, make sure you can start where you left off. Create a note, with all the necessary information, how you would continue and also with the reasons why you stopped.41

Review

All systems get cluttered and deteriorate if they are not maintained. Forte explicitly follows the tradition of David Allen’s GTD here.42 I consider these checklists to be fairly self-explanatory.

Weekly Review

- Empty the email inbox.43

- View the calendar.44

- Clean up the desk of your computer.45

- Empty the inbox of your note-taking software.46

There is no editing involved! This is just about putting the material into the PARA system. - Choose the assignments for the week.6

Monthly Review

- View and update your quarterly goals.47

- View and update your project list.48

- View your areas of responsibility.49

- View your “someday/maybes.”50

- Update how important and urgent the tasks are.51

So we have all three aspects system, workflow and habits together.

Summary of BASB

- BASB is a hybrid of (1) information management and (2) project management system. It is based on GTD. The important changes are the adaptations for collecting content for projects.

- The system PARA is a four-folder system ordered on a hierarchy of relevance to action.

- The workflow CODE mainly concerns the input to the system. However, use of the system for publishing is encouraged.

- Using the project checklists is the core habit for productive use of the system. The system is maintained on a regular basis. This is what the weekly and monthly reviews are for.

Now that we have an overview of Building a Second Brain, we will compare this system to the Zettelkasten Method.

Building a Second Brain and the Zettelkasten Method in comparison

Simplified, BASB is a source material feeder system for project-oriented self-organization. It is especially suitable for people whose projects are particularly dependent on source material. Oddly enough, the processing of knowledge seems almost to be considered a necessary evil, to be automated and simplified as much as possible. Thus, Forte writes in the processing step Distill:

Don’t worry about analyzing, interpreting, or categorizing each point to decide whether to highlight it. That is way too taxing and will break the flow of your concentration. Instead, rely on your intuition to tell you when a passage is interesting, counterintuitive, or relevant to your favorite problems or current project.52

Analysis, interpretation, and classification of resources and the thoughts they contain are essential to the processing of knowledge itself. It could not be clearer: The processing of knowledge, knowledge work, is explicitly not part of BASB. Knowledge work needs to be done, regardless, if you want to actually produce value. So, you will perform the actual knowledge processing outside the BASB system.

The Zettelkasten Method, on the other hand, is a method for processing knowledge. The analysis of single thoughts and their relations to each other is clearly a centerpiece. Project work, on the other hand, is in the periphery. In a way, the ZKM is agnostic to the use of the processed knowledge. We could spend a lifetime working with a Zettelkasten without publishing a single line of text.

Let’s go through the three aspects in order to elaborate on this:

PARA vs Zettelkasten

The system PARA is a filing system arranged by time relevance to action. Projects come before areas of responsibility because they have a short to medium time horizon, while areas of responsibility have an unlimited time horizon. Resources and Archives come last because they are usually neither a priority nor urgent.

The Zettelkasten Method is based on a hierarchy-free network. There are individual notes and their links. The structure notes can be used to create a hierarchy, but they are rather a just one representation possibility for a set of notes. One can create other structure notes with alternative hierarchies or even some with a non-hierarchical representation. In the Zettelkasten, one’s thoughts find an equal coexistence.

BASB is a cat, ZKM is a dog

Let’s say you want to breed pets. They are to be companion animals that keep people company. Both dogs and cats have been companions to us humans for thousands of years. But the way they form a relationship with us humans is completely different. This first decision, whether I breed dogs or cats, is a fundamental one. Certainly over many years of breeding I can make cats more obedient, loyal and stable in temperament. I can also make dogs more ignorant and moody after many generations.53 But fundamentally, dogs and cats have two completely different basic ways of relating to humans.

That’s the difference between BASB and ZKM. BASB speaks the language of action. ZKM speaks the language of knowledge. The basic categories of BASB are importance and urgency. These are categories of action. The basic categories of ZKM are atomic thought and its relation to other thoughts. BASB chooses as its filing categories PARA, a folder system that is a hierarchy of urgency. ZKM is a heterarchy of thoughts that can float freely in the ether like in the Platonic world of ideas.

Forte places himself in the tradition of David Allen’s Getting Things Done.54

Completed projects are considered the blood supply of the second brain:

I’ve learned that completed creative projects are the blood flow of your Second Brain. They keep the whole system nourished, fresh and primed for action. It doesn’t matter how organized, aesthetically pleasing, or impressive your notetaking [sic!] system is. It is only the steady completion of tangible wins that can infuse you with a sense of determination, momentum, and accomplishment.55 (Emphasis mine)

And last but not least: Progressive summarizing, Forte’s proposed method of processing resources, is just a method of highlighting a text. At no point does it leave behind the resource. Thus, not only is it not processing resources into knowledge, it is merely preparing resources so that they are easier to skim.

PARA brings in an element of restlessness.

The restlessness of PARA

PARA is not based on an assumed correctness of filing (for example, on a sophisticated metaphysics of categories). It is a production system that puts information where it is most likely to be needed. Because this is constantly changing, the whole system is subject to constant upheaval and reordering:56

PARA isn’t a filing system; it’s a production system. It’s no use trying to find the “perfect place” where a note or file belongs. There isn’t one. The whole system is constantly shifting and changing in sync with your constantly changing life.57

Resources and notes have no fixed location, but are always moved to where they seem to make the most sense. If one relates the three active folders (projects, areas of responsibility, resources) to each other, one could say that the internal purpose of the areas of responsibility is to supply the project folder with projects. The metaphor of blood supply that Forte chooses to describe the role of completed projects is perfect: “The blood supply to the brain is of absolute importance. Without blood flow, neurons die within minutes. If the project folder is not supplied with projects, the second brain dies. The central task of the user is to complete the projects and thus return the blood. Otherwise, your brain will suffer from a stroke.

I see a side effect of this as a problem. This dynamic brings a certain restlessness into the system. Nothing has its fixed place. For individual, small projects, this is not a problem. However, anything that is complex and exists over a long period of time needs stability and constancy. We need familiar places. This familiarity comes from going to these places and always being assured in the same way, “Everything is fine. Nothing changed. You are still welcome!”

My research on psychological entropy is a good example of what BASB is inappropriate for:

It took me a few weeks to build up the sections of my Zettelkasten that cover the topic of psychological entropy. In the language of BASB, this was a research project. While I did not have a firm deadline, I had two clear goals. First, I wanted to achieve “Feynmanian clarity.”58 That is, I wanted to understand the phenomenon to the point where I could explain it to someone without stuttering. Second, I wanted to build the structures so that I could smoothly incorporate new knowledge in the future. I wanted to create a place that seemed like an old acquaintance. The first would still have been compatible with BASB, but the second goal was not.

Not only do I have many such research projects. They also span disciplines and years. When I do a research day, I may well combine the results of 5 or 6 such research projects. This means that within hours I have to access knowledge that I have built up over a span of 10–15 years. If the knowledge were spread over folders in my second brain and I was forced to re-collect such amounts of knowledge, my work would not be possible. I would be too slow. If I have an idea, it must be realizable at this moment. I can only do that with my Zettelkasten, but not with the PARA system.

Forte recommends relying on system-wide search.59 But my experience with the Zettelkasten Method has shown me that as the size of the Zettelkasten increases, the search function becomes less reliable and more cumbersome to use. I’m already at the point where the search function has lost much of its usefulness. My Zettelkasten is simply too complex for the search to provide reliable access.

This problem is by no means only relevant for people like me. It results from the relationship between knowledge and the user. The problem described above always arises when one works at the limits of one’s own cognitive capacities. It is only a matter of time before one reaches this limit when using a system for a lifetime. For some, this point arrives after a few years and for others after 10 years. But one thing is certain: It will arrive.

This does not mean that BASB is useless! BASB provides a system for information and project management. It provides tools to meet requirements upstream of resource processing. BASB is something like a combination of forestry system and lumberyard. The Zettelkasten, on the other hand, deals with the actual processing of knowledge. The Zettelkasten Method, on the other hand, a carpentry.

BASB is a hybrid of (1) information management system and (2) project management system. The Zettelkasten Method is a system of creating an integrated thinking environment and working with it.

Once you understand this difference, there is nothing to stop you from using both methods in combination!

CODE vs Zettelkasten

The workflow CODE is a method of filing edited resources. At no point do you move beyond the resource inside the system. One could argue for it happening at the express step. But this is technically outside the system.

In contrast, the core of ZKM is precisely this processing of resources into individual ideas by extracting them from the resource and connect them to other ideas. Preparing the resource for later use is indeed a feeder method, and publishing content with the help of the Zettelkasten contributes to using and integrating the Zettelkasten. But both of them nevertheless belong to the periphery of the Zettelkasten.

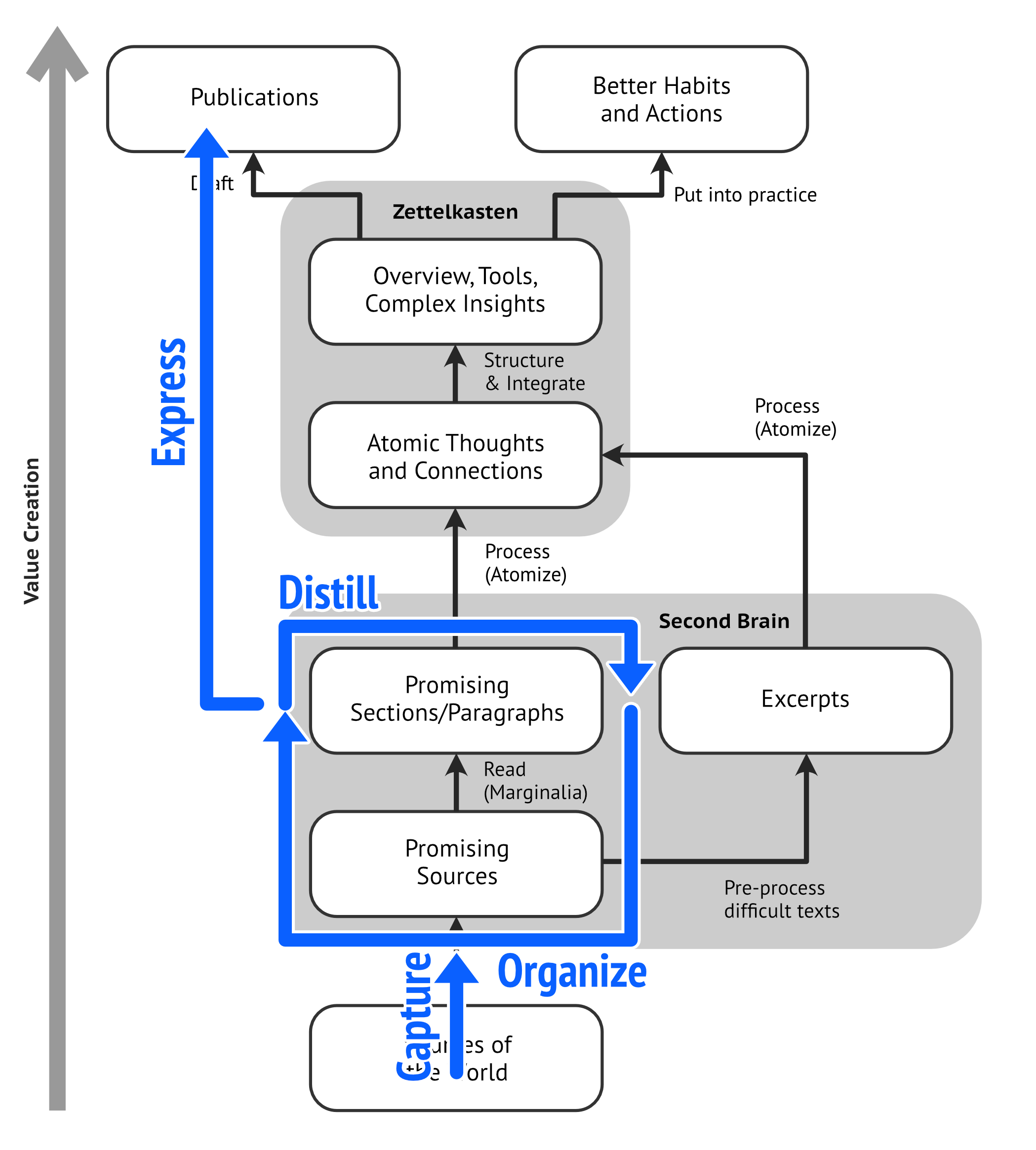

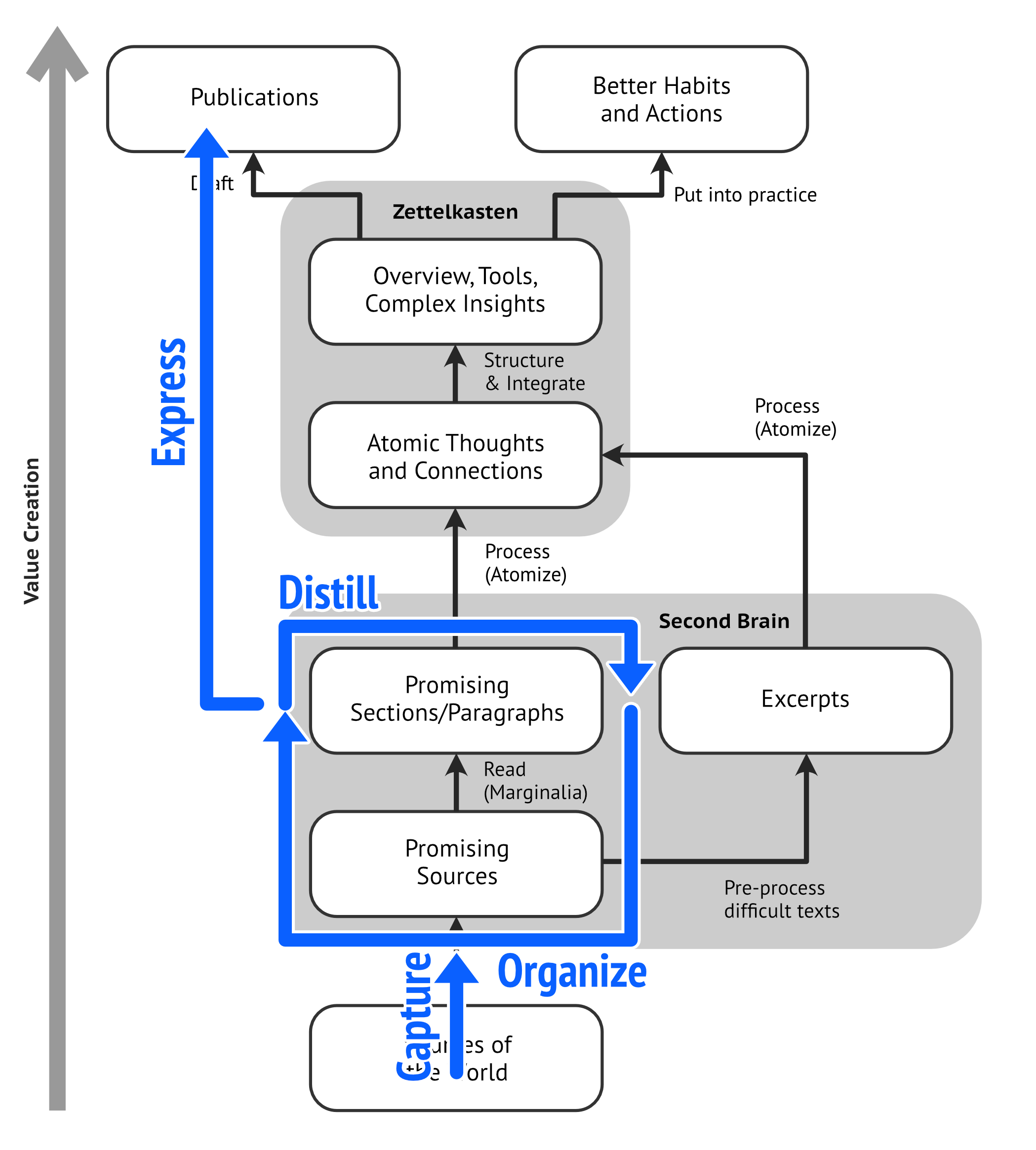

Thus, one could superimpose both methods and clarify this difference:

They focus on different sections of the overall value chain of processing knowledge.

Habits of BASB vs ZKM

Habits of BASB are the typical habits of an administrative system. It must be used in a certain way, and it must be maintained regularly.

The Zettelkasten Method is frugal as far as that goes. Rather, there are mere habit recommendations, such as setting up research days. But the Zettelkasten Method is rather another way of doing what you are already doing anyway. Therefore, there are two basic recommendations:

- Usually, you should not do anything in addition, but do what you are already doing with the Zettelkasten. Once you have learned the basic handling of your Zettelkasten, there should be no extra work.

- Working with the Zettelkasten benefits greatly from incorporating Newport’s deep work strategies into your daily routine. While these strategies are general recommendations to everyone, they fit the Zettelkasten Method especially well.

BASB and the ZKM are two completely different approaches to working. But their differences don’t come from the fact that they solve the same problem differently, but that they address different parts of the knowledge-based value chain. This makes them not only easily compatible. In fact, I think it is advisable to combine them. That way, you get the best of the worlds of productivity-focused self-organization and deep understanding-focused integrated thinking environments.

BASB and ZKM

Let’s look at the above graph again:

From this graph, we can see that BASB manages exactly what is outside the Zettelkasten. BASB is not about creating a second brain in the direct sense. Rather, it is about handing off to the system all that does not belong in the brain. Again, BASB is in the tradition of GTD and accomplishes the same thing.

The system and workflow of BASB and the ZKM are easily compatible. We use BASB for organizing resources and excerpts. Our Zettelkasten serves as our integrated thinking environment. Here we process the collected resources and excerpts into atomic thoughts and link them together.

From the PARA system, the Zettelkasten is responsible for both resources and the archive. Projects and areas of responsibility are divided: Content belongs in the Zettelkasten, tasks in the task organisation.

The project habits can be easily transferred to ZKM.

The routine at the start of the project would look like this:

- Create a structure note for your project in the Zettelkasten. This is the place where you collect everything. The difference is that you just create links to needed notes instead of moving the actual files. This applies to notes anyway, but also to excerpts and resources in the form of PDFs, books, etc.

- Collect: Collect everything you know about the project on the structure note.

- Review: Search your notebook for existing knowledge and refer to it from your project structure sheet.

- Search: Systematically search all other places. (Like collections of unread PDFs, link lists, etc.)

- Move: Moving to a project folder is unnecessary. All notes stay where they are.

The result is a note that contains all information about the project. It refers to all notes that are relevant for the project. However, it also references resources and excerpts that are outside the Zettelkasten. So, you process everything until you have one structure note that just links to notes and comments on them and their relationships.

The routine at the end of the project, would look like this:

- Mark and Cross Out are part of task management and have nothing to do with the Zettelkasten.

- Review and Move are already partially done, in extreme cases even completely: After all, you have developed all thoughts in the Zettelkasten. They are already in the Zettelkasten and completely integrated into your base network. For every note you write, you can check directly when you create it whether the note is usable for another project. When you finish the project, there’s one thing you can check: if something came up while you were writing the manuscript that you want to feed back into the Zettelkasten. That’s what I call “processing back.”

- If project becomes inactive is superfluous. Everything is in the Zettelkasten anyway.

BASB’s maintenance habit review has nothing to do with processing knowledge, but with project and task management. We use the habits to clean up the PARA system. The Zettelkasten remains unaffected.

My personal lessons from reading Building a Second Brain are as follows:

How I use BASB myself

- The inbox is coming back. I have reintroduced inboxes. Originally, I eliminated all my inboxes and immediately put everything into the right place. I actually dislike inboxes, but have accepted them as a necessary evil. I found that I did stay in the workflow more easily when I experimented with using an inbox again after reading BASB. However, I now have to work on my resentment of emptying the inbox regularly.

- Reviews are coming back. Because I have an inbox again, I have to do reviews again – at least to empty my inbox. In my task management, the task is “Clean up the workspace” and consists of 4 subtasks: (1) throw the browser tab addresses into the inbox, (2) empty my task management inbox (I use Things), (3) clean up my desk, and last but not least (4) clean up my study.

- An old routine is coming back. (“Verzettelungsroutine”) Originally, I had my own version of Feynman’s 12 Favorite Problems. I had a collection of notes on various topics and projects that I basically checked for possible linking opportunities when I created a new note. After a long hiatus, this is coming back.

- I have darlings. I use PARA as a basic principle for organizing resources and tasks. I manage resources and short notes with TaskPaper. Originally, I had a purely thematic ordering. I have now abandoned this in favor of a variation of the PARA system. I just call them my darlings because they are not just problems but, as in the case of a short story collection, creative projects.

- I have switched from TaskPaper to Things. Things is faster, less complex, and provides ready-made task management functions. I am not a professional task manager. Having once lost two weeks to Emacs, I don’t want to make such a mistake again. Things is inspired by GTD. It’s a great fit. The only thing I’m missing is the complexity that TaskPaper allows. That’s important for some of my long-term research interests, where there are complex dependencies that I map by deep indentation. But there’s already a solution in sight: TaskPaper will take over my long-term research.

- I value effectiveness more. I have changed my work style to more effectiveness (publishing) and less efficiency (basic work, indirect work).

However, I do not follow one recommendation: Forte recommends using the PARA structure across all programs. Forte reasons, personal knowledge management systems should follow the same patterns as the task and project management system because they have the same job: They are productivity tools.

My Zettelkasten follows a completely different logic than my task and project management system. Even my research file, where I collect promising resources, article ideas, and the like, does not strictly follow the PARA system, but rather an ARA system. I have divided the projects I have assigned to the areas of responsibility by size within the areas of responsibility. Small items are not only easier to accomplish, but are often part of larger research and writing projects. So, within the areas of responsibility, I have divided the projects according to their size and thus achievability.

Strictly speaking, I do not follow PARA, but an overarching principle. I understand PARA as an incarnation of this overarching principle: the iceberg of urgency.

PARA as an iceberg

In my view, PARA is a version of a general principle of task hierarchy:

Important projects are urgent.

Models such as the Eisenhower Matrix suggest that the importance and urgency of tasks and projects are two independent properties. While this is true in the short term, it is not true in the long term. For example, it is urgent that I clean up my workspace today so that I have a clean start to next week. But cleaning up is not important compared to finishing this article. Tidying up is urgent because the mess is screaming at me right now, but it’s not important. I could go on working in the mess for years. Completing this article, on the other hand, is an important milestone for the Zettelkasten Project. Whether I finish it a week earlier or later, on the other hand, makes little difference.

In the long run, over years and decades, important projects are always urgent. It may not be urgent that I publish this article next week. But while I could put off cleaning up for life, publishing this article can’t wait more than a month.

The principle Important projects are urgent! is a second-order principle that arises from the application of the Eisenhower matrix: It can be used not only as an inventory of the general situation, but also as a guiding principle for how we should shape our lives. We should shape it in such a way that we do as few unimportant things as possible. This increases the meaning and significance of our lives. We should treat the important but not urgent projects as if they were urgent. This makes us productive.

This results in a unifying hierarchy that combines importance and urgency.

PARA follows exactly this principle. The areas of responsibility are what is important but not urgent. Yet they continually produce projects that we treat as urgent. Indeed, projects have a specific goal and usually deadlines. PARA is a way to continually transform important but not urgent into important and urgent. I think this is one reason why BASB works as a productivity tool.

PARA has a kind of iceberg dynamic. Only the smallest part, the projects, float above the surface. The rest remains hidden below the water’s surface. But below its surface, water freezes onto the iceberg and makes it larger. As a result, the iceberg gains more buoyancy and more of it protrudes above the water. The areas of responsibility and resources give the overall system a greater buoyancy. In a sense, they push projects above the surface of the water into our consciousness. And if you want to stretch the metaphor a bit, the ice above the water can be mined and drunk as precious fresh water.

My above criticism of unrest is put into perspective at this point. Unrest is a necessary side effect of urgency. This systemic restlessness is balanced by the ongoing focus on projects. While working with BASB’s second brain, we fixate on the projects at hand while ignoring the rest of the system’s restlessness. We can ignore the restlessness because it is hidden from us. Most of the iceberg remains under the water. The folders for areas of responsibility, resources and archive remain closed.

My Zettelkasten provides the necessary peace and quiet for knowledge work. It gives me a firm foundation. The restlessness of PARA does not affect my Zettelkasten, only my resource management. For my overall system, the purpose of my PARA is to provide resource collections, sorted into projects. PARA replaces my old system here, sorted by topic, and directs my research toward specific projects. This dynamic helps me through two possible directions:

- When I assign a resource, I go through a hierarchy of actionability. That is, the resource is filed where it is most likely to benefit a project.

- The more resources I assign to larger and therefore more difficult to implement projects, or even general areas of responsibility, the more likely I am to structure the project into subprojects. This leads to a larger project being divided into smaller and thus more actionable sub-projects, or even to projects emerging in areas of responsibility.

Closing words

Building a Second Brain60 and the Zettelkasten Method concern completely different sections of the knowledge-based value chain, starting with the world’s resources and culminating in publications and their practical implementation.

BASB concerns the management and rough preparation of resources for later use and then proposes to proceed from prepared resources directly to publication and implementation. This means that the actual knowledge work must take place in the manuscript.

The Zettelkasten Method, on the other hand, is primarily concerned with the actual knowledge work and suggests that resources be processed thoroughly and deeply so that ideas and their connections to each other are revealed in Zettelkasten. This shifts the knowledge work into the Zettelkasten.

The two methods are easy to combine because of their little overlap.

For me, the reading Building a Second Brain had a similar effect to reading Deep Work 60 by Cal Newport. Both books prompted me to improve my system. I have been working with BASB as part of my overall workflow for a few months now and am very pleased. I can give a clear recommendation.

-

David Allen (2015): Getting Things Done. The Art of Stress-Free Productivity, Elcograf: Piatkus. p. 14. ↩

-

Forte 2022, 212 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 140 ↩

-

David Allen (2015): Getting Things Done. The Art of Stress-Free Productivity, Elcograf: Piatkus. p. 16. ↩

-

Jacob B. Hirsh, Raymond A. Mar, and Jordan B. Peterson (2012): Psychological entropy: a framework for understanding uncertainty-related anxiety., Psychological review, 2012, Vol. 119 2, pp 304-20. ↩

-

Forte 2022, 108 ↩

-

Credits for this term go to Alex Kahl. ↩

-

Jacob B. Hirsh, Raymond A. Mar, and Jordan B. Peterson (2012): Psychological entropy: a framework for understanding uncertainty-related anxiety., Psychological review, 2012, Vol. 119 2. ↩

-

Forte 2022, 90 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 91 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 91 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 94 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 90 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 94 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 94 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 94 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 94 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 94 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 90 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 95 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 86 ff., 102, 103/104 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 102 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 102 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 102 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 102 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 102 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 120 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 140 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 151ff ↩

-

Forte 2022, 201 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 203/204 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 204 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 204 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 204 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 205 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 206 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 208 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 208/209 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 209 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 210 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 212 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 213 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 213 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 213 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 214 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 215 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 216 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 216 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 216/217 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 217 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 140 ↩

-

You can guess if I’m more of a dog person or a cat person. :) ↩

-

Forte 2022, 212 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 108 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 104 ↩

-

Forte 2022, 104 ↩

-

Feynmanian Clarity is reached when you can explain a concept fluently. To me, it is the stop criterion for the Feynman Technique. ↩

-

Forte 2022, 158ff ↩