Reading Habits: Putting It All Together

I am moving next month, and so I though about getting rid of stuff in my life. There are lots of books I’ve read, but from which I never processed all the notes.

I know for sure that at I finished least one book in the collection about two years ago! You see, I was, and still am, vulnerable to the Collector’s Fallacy. While I try to get through the pile of books, I reviewed my reading process. This is a summary where I put together some of the topics I already wrote about

Recap: Learning Efficiently with a Zettelkasten

Learning is all about coverage, practice, and insight. We’ve already established that the Zettelkasten is an apt tool to facilitate learning. Obviously, a Zettelkasten helps with getting practice and generating insight:

- Practice: you write about what you read, revealing gaps in your understanding. Only then can you deliberately work on your deficiencies.

- Insight: you obtain knowledge when you add notes to your archive and connect them to other items in your system. To use links between notes to create a hypertext in your archive is key.

The first component of learning, getting coverage, is about reading techniques. Reading techniques are important to the Zettelkasten workflow, because you need input to create something new. They’re not a part of the Zettelkasten system’s components, though. Reading takes place before you use the Zettelkasten.

When we think about how to read in the context of learning, we should ask how to create useful notes most efficiently. Creating notes efficiently is the desired replacement for committing information to memory. Both are ways to expand your knowledge; to take lasting notes is just a smarter way to do so. Reading is an apt means to learn, though it lasts only briefly. Taking notes is another means, but one with permanent results.

Get Information Out of a Text

I’ve suggested that reading to expand knowledge can be split in stages: collecting and processing. Let’s have a look at both of them.

Collection Stage

The collection stage is tied to getting coverage. We want to optimize this step. Here, it matters to be fast and generate lots of intermediary products to work with later. Make proper reading marks quickly, but don’t stop there:

If you’re reading a book, I would recommend against highlighting. This processes the information at a low level of depth and is inefficient in the long run. A better method would be to take sparse notes while reading, or do a one-paragraph summary after you read each major section. — Scott H. Young

Highlighting and writing notes in the margin only is too superficial. Highlighting everything like a madman doesn’t yield better understanding by itself, and when the notes are in the margin only, you will need to look at the book to retrieve your own thoughts every time. That’s highly inefficient.

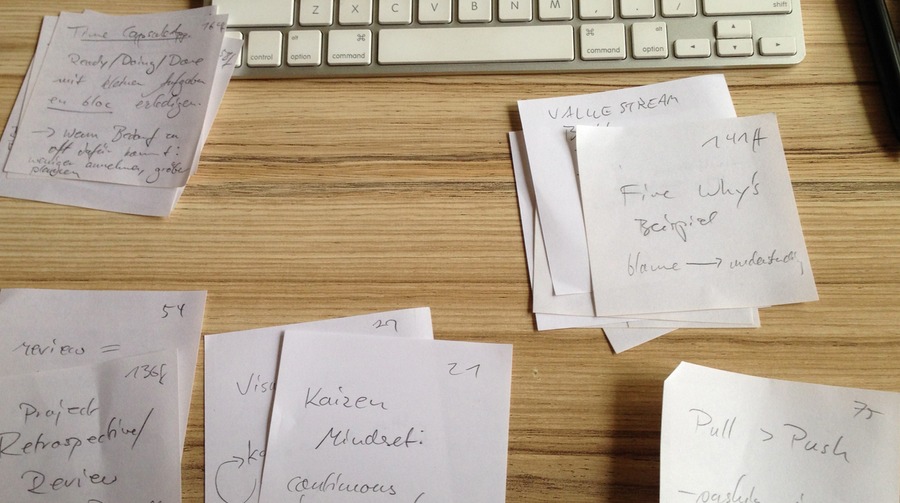

Instead, write about the interesting stuff in your own words, to avoid the risk of not understanding what the text is about; put unobtrusive marks into the page margin to aid the eye when you scan a page for useful pieces later. Write down interesting parts of a text immediately on a sheet of paper. These notes will help processing the text as a whole later, when you’re done with reading. Prefer to create more of these intermediate notes so you have a lot to chose from in the next stage. I use a single square paper note for every aspect I find interesting. I usually put little dots in the page margin to denote where on the page something interesting is located; only seldom do I resort to using elaborate marks.

If you’d like to differentiate between the various functions a paragraph in a text can have, look out for signal words. For example, the following literal devices may indicate that the function is to build a mental model: schema, allegory, analogy, hypothesis, metaphor, representation, simile, theory. Put a corresponding “model” mark next to these.1

Processing Stage

In the processing stage, I pull out the notes and create clusters before I add anything to my digital note archive. The dots in the page margin help to look up details if needed in this stage.

Don’t worry about re-usability of the information you keep. A lot of the notes we take tend to be wasteful at first.2 Since we’re trained to do something useful, though, we expect our work to bear fruit, or else we cease to continue. Make the notes available for later access to keep up your morale. Integrating notes into your trusted Zettelkasten system strengthens your memory as a side effect. Because the step of integration is accompanied by creating connections, you have to find suitable associations both in your note archive and in your head. The latter will persist longer than the single note by itself. Rely on your Zettelkasten to remember the details, so your mind has capacity to worry about stuff you really need.

The same holds true for collecting: if you speed-read a book and amass pieces of intermediate notes on paper, you may wonder if all that stuff is going to be relevant. The answer is: probably not – but who knows just yet?

We can only rely on the process of getting good coverage. With good coverage, we don’t miss opportunities to take lasting note of information. When we process all the stuff we’ve collected, we can allow ourselves to be picky. Only then, after we have a full understanding of the text, are we able to write down information concisely and to-the-point.

My processing stage hasn’t changed a lot in recent years. To create clusters from the intermediate by-products of reading has proven to be useful to get started writing permanent Zettel notes. I didn’t do this two years ago, and keeping the bigger picture of the text in mind this way was hard. Clusters, on the other hand, make me think about the text as a whole before I dive in to copy information.

I found that the more I know about a topic, the longer integrating a note properly takes. After I decide which keywords fit, I query the archive for similar Zettel notes and try to find direct connections so I can add links to the notes themselves. Sometimes, I have to follow existing trails for a while until I discover a whole network of information to which the new note contributes. All this takes some time, but it’s a fun and adventurous endeavor, in an Indiana Jones-way of uncovering forgotten secrets.

Integrating notes will become the bottleneck of your workflow sooner or later, too. It’s the only task with a time consumption proportionate to the size of the archive:

- Reading can be done without any prerequisites, one text after another, and chances are you’ll get faster instead of slower with practice;

- Collecting interesting information is consistently fast, too, since it depends on reading only;

- Writing the final note itself sometimes is easy, sometimes it takes time, but the actual writing is mostly independent from other steps;

- With a digital archive and full-text search, retrieving notes is blazingly fast, no matter how many notes you have;

- Only creating connections takes more time the bigger your archive becomes. Obviously, that’s because there is an increasing amount of link target candidates. That’s a good sign, a sign of externalized cerebral growth!

Update 2017-06-06: Sascha made a video about the processing of notes.

How All That Fits Together

The pieces we recapitulated make up for two thirds of the bigger picture:

- On the top, there are the fundamental principles. They are based on reflections on the processes, for example: what is learning about? Which steps do you have to work on? How can you get more out of your reading?

- In the middle, there’s general advice on using the Zettelkasten. This layer is about the habits: how do you implement connections to mimic the way our brain works? The recent post about identifiers falls under this category, too.

- At the ground-level, there are the hands-on tips: which tools are useful? How do you apply the principles to your use case?

Looking back, I didn’t write a lot about the last part, the tools. I have promised to tell you more about the software I use already. Although there’s lots of other stuff to say, I am going to talk about tools for a while to fill in the gap. Then, we’ll have a full slice through all layers, from top to bottom, to make understanding the Zettelkasten method easier.

If you want me to review a particular application, leave a comment or drop me a line: I’m @ctietze on Twitter.

-

Keith Oatley and Maja Djikic (2008): Writing as Thinking, Review of General Psychology 1, 2008, Vol. 12, pp. 9–27. ↩

-

Niklas Luhmann (2000): Lesen Lernen, Frankfurt am Main: Zweitausendeins, p. 156. – English translation online: “Learning how to Read” ↩