Optimal Concentration: Dedicated Sessions Are Your Success Recipe

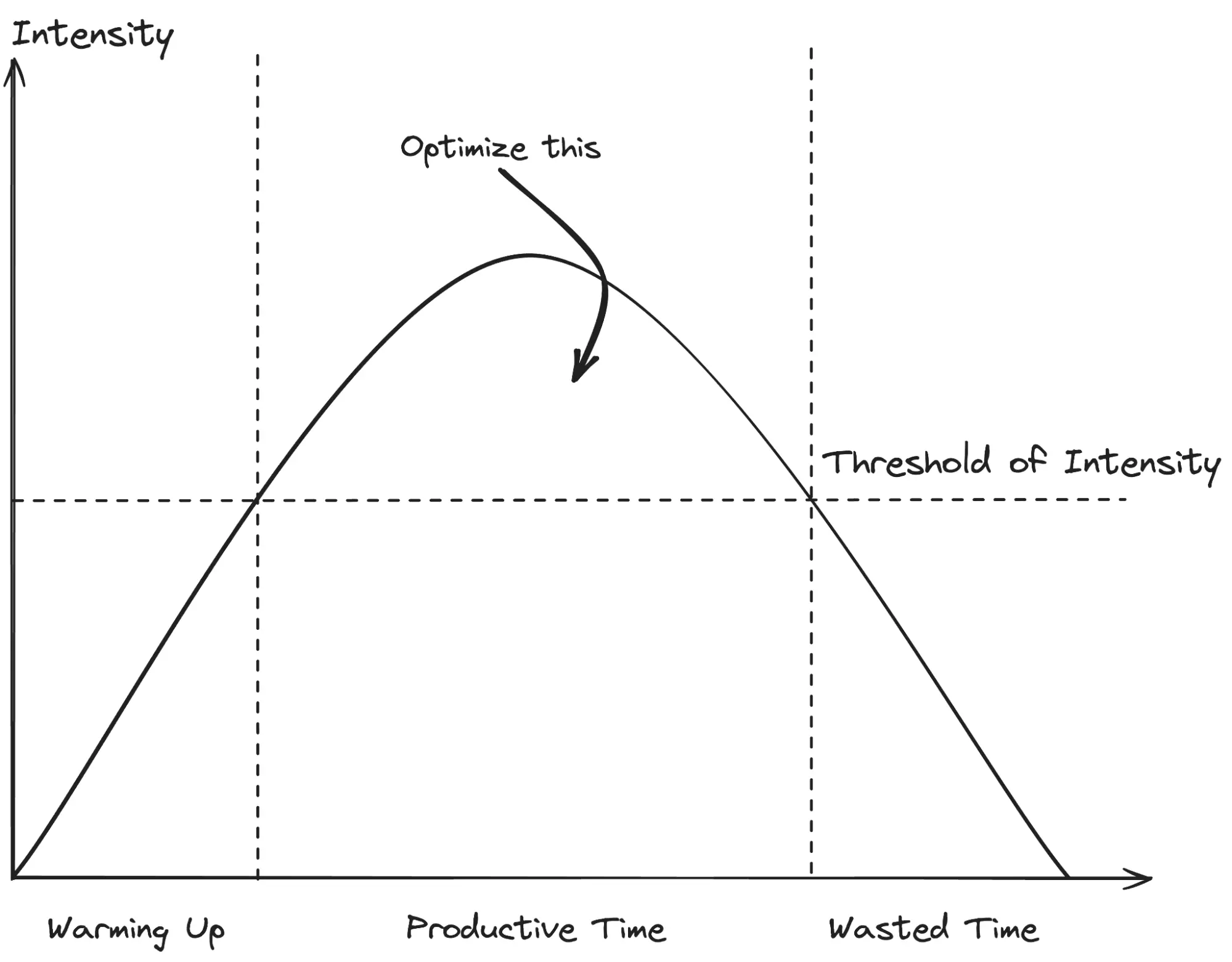

A Zettelkasten session has the following form:

- the warm-up phase,

- the productive phase,

- the busy but unproductive phase.

Warming Up

When we sit down at the Zettelkasten, we need a while to reach operating temperature. To do this, we need to activate our brain, orient ourselves within the Zettelkasten, and engage the most important areas of our memory, among other tasks.

The duration of this warm-up phase depends on more than a single factor; it also depends, for example, on our ability to concentrate, our habits, and the working environment.

In the best-case scenario, this takes 10 minutes. This applies to an experienced person in a familiar environment, conditioned to perform mental work, and who knows what to do next.

In the worst case, this takes 2 hours. That sounds long, but it is the reality for many people. They meander through their day, desensitizing themselves to dopamine with mindless smartphone scrolling in the bathroom, listening to entertainment podcasts on their commute, and chatting with colleagues before finally sitting down at their desk. Then they kill more time with distractions. Eventually, the pressure builds, and they start working, but it takes them a while to get into the right mental state for work.

They may not even get past the magical thinking threshold all day. Their capacity is already lowered by desensitization to dopamine and mindless activity. Their work environment encourages distracted work and multitasking.

Productive Phase

The productive period is the time we are fully immersed in our work. It is a time of “high flow”. We are at the upper edge of our mental capacity.

Concentrating at a high level is extremely strenuous physically. Many people can’t sustain this level of operation for more than 1–2 hours.

If we take professional chess as an example, 5–6 hours of deep concentration alone is enough for physical fitness to become a decisive factor in the endgame. This is the reason why Magnus Carlson makes his physical fitness a priority:1 If the limit for extreme thinkers like professional chess players is reached after a few hours, it is likely that the limit for less trained individuals is reached much earlier.

Then there is the working environment. The problem of concentration is one reason for us to design The Archive as a “Distraction Free Editor”. By now, many people have realized that an editor like the iA Writer (not a sponsor) helps to facilitate concentration compared to other writing programs like Microsoft Word. This realization has yet to penetrate the world of Integrated Thinking Environments (“ITEs”).

Unfortunately, many people’s thinking surface still looks like an airplane cockpit. Recognize the power of the blank page, dear thinker!

The Busy, Unproductive Phase

The busy but unproductive period is the time when we are still trying to work with a high level of concentration, but at best imagining that we are performing at a high level. In reality, however, we are merely busy but not productive.

The reality for many people who strive for high performance is that they are often busy but unproductive.

This can be disguised by using the level of effort as a measure of one’s productivity. It can also be disguised by frontloading: When you do the important tasks at the beginning of the day and unimportant tasks later. You get the impression that you have accomplished a lot during the day because you have done the most important things. However, with access to deeply concentrated work, you would have completed the unimportant tasks in a fraction of the time.

Based on my personal experience, the ratio is between 1:5 and 1:8. In other words, if you concentrate hard, you would manage about 5 to 8 times as many of the small and rather unimportant tasks.

The Zettelkasten and the Magic of Thinking

The individual note is the substance that makes up your Zettelkasten. This means that the quality of the individual Zettel determines the quality of the Zettelkasten. In my experience, not every note needs to be a stroke of genius.

There are notes that are not too complicated. If you want to add a definition, for example, that’s not difficult.

But there are notes that you can only write when you are in the zone of magical thinking. Some ideas only come to you when you spend some time in the magical thinking zone. These are solutions to challenging cognitive problems, brilliant ideas and so on. This is especially true when you are on the edge of your mental abilities. Programmers know this from their work: For complicated programming tasks, you sometimes need the certainty that you can spend half a day or even a whole day working uninterruptedly on just this one task. If the morning is split up by a meeting, it may not make sense to tackle such a task at all. Incidentally, this is a huge problem for programmers in larger companies. The many and usually completely pointless meetings, which often only serve to enable some managers to justify their job, make much of their work almost impossible.

Because there is this correlation between the intensity of concentration and the time it takes to achieve it, your personal weekly structure has a significant impact on what thinking tasks you can tackle.

I personally need to concentrate on working with the Zettelkasten for at least 2 consecutive mornings (between 4 and 7 hours each) over a few weeks to achieve reliable “aha” moments. These moments stand for deep insights, ideas that I am excited about, and leaps of knowledge in my work. I’ll give you a few examples to illustrate this:

- In his books, Csíkszentmihályi equates flow and optimal experience. But this is not correct because there are optimal experiences that are not also flow experiences. This has given my philosophical work a great leap forward, as I was able to expand Csíkszentmihályi’s flow model so that it can better represent growth experiences. Based on this insight, I have changed my training to my great satisfaction.

- The realization that bodybuilding methods, Crossfit, and interval training can be classified at a higher intensity level than, for example, pure strength training, sprinting, jumping, and throwing, has led to me being able to improve Peter Attia’s training model (as yet untested).

- After realizing that dopamine does not map to the reward itself, but to reward prediction errors, it has changed large parts of my view of existentialism and its relationship to the functioning of the human psyche.

- I had originally intended to use the principal-agent problem to think about politics, but it allowed me to expand and significantly improve my model of the future self.

These sudden leaps in my work are only possible when:

- I am in the zone of magical thinking. I need to have warmed up mentally for this.

- I am familiar with the zone of magical thinking. I need to practise this at least twice a week.

- I have enough time and energy after my “aha” moment to hold on to its consequences. After all, after a deep realization, I have to create many new links in the Zettelkasten, rearrange structure notes, etc.

I am very often on the edge of my cognitive capacity. This means that, to a large extent, I can only do my work when I am in the zone of magical thinking. This means that I inevitably have to plan my work in such a way that I spend a lot of time in this zone.

Of course, I sometimes just file a note with a few links in my Zettelkasten. Processing back2 a published article doesn’t require too much concentration on my part. But that doesn’t change the fact that a large part of my work depends on my successful weekly planning. In relation to the Zettelkasten: I can only use my Zettelkasten to its full extent if I plan my week carefully.

This is often a source of error that some Zettelkasten users don’t think about. They want to use the Zettelkasten because it promises to improve their mental work. Some want to delve deeply and extensively into a topic. Some want to use the creative power of the Zettelkasten to elevate their business to a new level.

But all of this requires space for deep, focused work regardless of the Zettelkasten. That’s the premise of the book Deep Work by Cal Newport. There are tasks that you can only tackle if you have enough mental space to tackle deep work. For example, I can’t learn programming if I set aside 10 minutes every morning for it. A programming session must have a certain minimum length.

Deeply concentrated work with the Zettelkasten must fulfill the conditions that enable deeply concentrated work in general.

For practice

- Plan your deep-focus work for the week. You can find an example here: Practical Integration of the Zettelkasten Method: My Deep Work Days. You can find more inspiration in Deep Work by Cal Newport.

- Consider the phased progression of a single session: use appropriate tasks to warm up, take full advantage of the productive phase, end the session or switch to less difficult tasks when the productive phase is over.

- If you use advanced methods of self-organization: Measure your productive time and use any strategies and tactics to optimize productive time.

Bonus

Here is an unsorted list of tools to optimize the productive time of a session. These tools are part of the “nootropic lifestyle”, one of my core projects. The idea behind it is to have the same attitude towards your mental performance as professional athletes have towards their physical performance.

- Keep your organs healthy, your brain included. There is good evidence that local energy bottlenecks play a role in concentration and willpower (source). Therefore, improve your brain’s energy metabolism by providing it with sufficient micronutrients and endurance training.

- Avoid any stimulation in the morning. This includes intense music, coffee, social media, sweet foods, sweet drinks, media with a feed function, etc. This sets the threshold for stimulation high so that your work is not stimulating enough to engage you on its own.

- Start the morning with an effort. Exercise or cold showers are good methods for this. The effect is the opposite of stimulation: the threshold drops, and your work becomes more engaging.

- Work out reliable warm-up methods. I often start my session in the “second brain”. This means, for example, that I structure article ideas or work out note ideas in the “second brain” first. If I can schedule Zettelkasten sessions at least twice a week, it only takes a few minutes for my brain to warm up, and I’m drawn to the Zettelkasten almost on its own.

- Your diet should keep your blood sugar stable. For example, if your diet is high in carbohydrates, your diet before and during the session should consist of low glycemic foods.

- Experiment with long pomodoros. The usual Pomodoro intervals consist of 25 minutes of intense work and 5 minutes of rest. In my experience, this ratio is not correct. For me, intervals of 40–60 minutes have proven to be effective. The more complicated a task is, the longer the intervals should be. Intervals of 25–30 minutes are suitable for routine tasks such as working through emails.

- Use intermediate routines. Light to intense exercise improves your ability to concentrate. 2–3 minutes of vigorous exercise work wonders and can extend your productive phase.

- Experiment with not listening to music or only nature sounds while you work. I myself was a big fan of finding the right music and conditioning my sessions to the music for a long time. Now I almost never listen to music or only nature sounds in the morning. If you are used to being stimulated by music, this can take a few weeks to get used to.

- Use a daylight lamp to start your work if you can’t get natural sunlight in your eyes. I live quite far north and get up early. That’s why I work with a daylight lamp for the first few hours. The effect is greater than most people expect.

Christian’s comment: Sascha has already mentioned Paul Graham’s classic on the “Maker vs Manager Schedule”: what do you do in such a horrible reality? That’s why I recommend a Zettelkasten to fellow programmers, because it can spread out the ideas over a longer period of time and buffer against disruptions. Complex problems, such as the concurrency of processes, cannot be solved quickly between noon and midday. It takes hours or days. All the “spontaneous ideas” that are needed are also a continuation of what is already known and thought about - you have to have the time to think and try things out. If you can’t go into isolation for a week and work on serious bugs, you have to find some other way to make up the time. A Zettelkasten routine designed to be productive is ideal.