Posts tagged “note-taking”

Universal Questions for Any Note-Taking System

Dear Zettlers, Here are some universal questions for any note-taking system.

What do you want to build for your future self?

The ability to store a note quickly, for example, benefits your

present self. Possessing a valuable note is what your future self

will be grateful for. Since the Zettelkasten aims to be a lifelong

partner, it is a future-oriented tool. This orientation is

methodologically correct, since you are not keeping notes for

yourself, but for your future self. Your actions should therefore

not be aimed at making it easy now, but valuable, and first and

foremost, to create value in the future.

The Collector’s Fallacy and Reward Dependency

Dear Zettlers, During a coaching session, I talked about a specific incarnation of the Collector’s Fallacy: Buying books and never reading them. My client correctly identified part of the cause for his behavior: He is using a Kindle to read. There, it is super easy to buy a book. So, when he sees a book that seems interesting, he buys it straight away. Part of the cause of this behavior is easy access.

How to Improve Your Zettelkasten by Learning from Athletic Training

The benefits of your Zettelkasten highly depend on the longevity of each note. Since the Zettelkasten as life-long companion and comrade in the battle for and against knowledge is a long-term endeavor, it is crucial that you create notes and structures that will last a long time. The minimum goal should be that they last a lifetime, so they are optimally designed for yourself. Ideally, they last forever, so future generations can benefit from your work as well.

From Fleeting Notes to Project Notes – Concepts of "How to Take Smart Notes" by Sönke Ahrens

Terminological troubles beset the account of note categories in How To Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens (Ahrens 2017). The book reads as though it emerged unedited from the author’s Zettelkasten. The most important type of note doesn’t have a name. This post aims to settle the record.

Ahrens discusses five categories of notes: three main descriptive categories of notes: fleeting note, permanent notes and project notes; and two subcategories of permanent notes: literature notes and Zettels, although the term Zettel occurs nowhere in Ahrens (Ahrens, 41). Italicized terms are defined in "Note categories in detail" below, after some remarks on the components of a Zettekasten and on workflow in the Zettelkasten Method according to Ahrens.

The Zettelkasten Method for Fiction II – Collecting and Processing Building Blocks of Story

In part 1 we concluded that knowledge is knowledge, independent of its source. Applying the Zettelkasten Method to fiction books does not change anything if we are dealing with knowledge. But if you want to use the Zettelkasten Method to analyse a story as a story? Then you need to know what to look for besides knowledge.

The Zettelkasten Method for Fiction I – Knowledge is Knowledge

Quite frequently, the question how to make the Zettelkasten Method work for fiction arises. The simple answer is: There is no need to modify the Zettelkasten Method because it only provides the overarching architecture for your notes and their connections. If your sources are fictional or non-fictional is just a question of the content your notes hold.

All notes are malleable: Strive for permanently useful notes, not permanently unchanging notes

Here’s a highlight from the forum from recent days. User @zappino4 asked: I am trying to understand the relationship between literature notes and permanent notes. My doubts are the following:

Q&A #3 - Some tips on how to write good notes

This episode: Always think of your future self as if you encounter a different person than yourself.

Baker and Me -- Joe Pairman Uncovers Universal Principles

I’d like to highlight this article by Joe Pairman: Take notes as online help for your creative future self. The rare feature of this article is that Joe is extracting universal principles by comparing one of my articles with ideas of Mark Baker from Every Page is Page One. (Affiliate link.)

Note Archive for Music?

Reader Kekeli reached out via e-mail a while ago and told us about an interesting problem: how do you organize, annotate, and file audio files?

This must be a problem similar to organizing video footage. In other words, it must be a problem that’s been solved at least once over the years for DJs.

I’d treat audio files like PDFs: it’s source material that needs to be managed, but apart from maybe simple tagging in the reference/audio management app, I’d write most stuff as regular Zettel notes in my Zettelkasten note archive and reference the source material from there.

If you happen to know a good way to file and annotate non-textual data like audio tracks, please share with us in the comments!

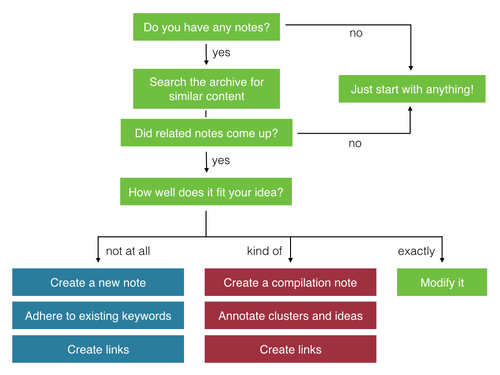

When Should You Start a New Note?

Say you start with a fresh Zettelkasten or you learn more about an existing topic. You write your note and expand the text – and then you ask yourself this: should I create a new Zettel? Should I split this up? Can I attach this detail there? Finding an answer is pretty easy as the scenarios are limited:

Reading for the Zettelkasten Is Searching

If you work with the Zettelkasten Method you have to deal with a lot of reading. It is obvious that it is often not very obvious what to include into your archive and what not. I chose to create a typology of items to serve me as an epistemiologic amplifier. If you know how things look in general (type) you can find specific items more easily. I struggle a little bit with finding the correct english term. They are not themselves thoughts neither are they Zettel types. There are six of them:

Fake Progress

With the help of intentions and promises, he maintains the honest impression that he is moving toward the good, yet all the while he moves farther and farther away from it.

—Søren Kierkegaard

Making decisions isn’t progress. Planning soothes your mind. But it’s a false sense of accomplishment. You still haven’t done anything by then.

Similarily, reading itself isn’t progress. We have learned a bit, but until we process the information, we haven’t yet succeeded.

Remember the Collector’s Fallacy:

‘[T]o know about something’ isn’t the same as ‘knowing something’. Just knowing about a thing is less than superficial since knowing about is merely to be certain of its existence, nothing more. Ultimately, this fake-knowledge is hindering us on our road to true excellence. Until we merge the contents, the information, ideas, and thoughts of other people into our own knowledge, we haven’t really learned a thing. We don’t change ourselves if we don’t learn, so merely filing things away doesn’t lead us anywhere.

Reading is cheap. Reading is easy. Processing notes is hard and time-consuming. But the hard work is the work that matters in the long run.

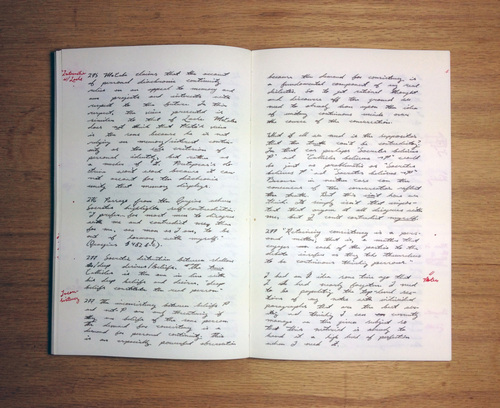

Keeping a Study Log and Extracting Zettel Notes From It

Dan Sheffler, who you might know for his valuable comments on this site already, has an interesting workflow: first, he captures ideas in a study log while reading; then, he picks the gems and writes Zettel notes later. This difference of “engagement notes” and “memory notes”, as he calls it, fits the Zettelkasten method well.

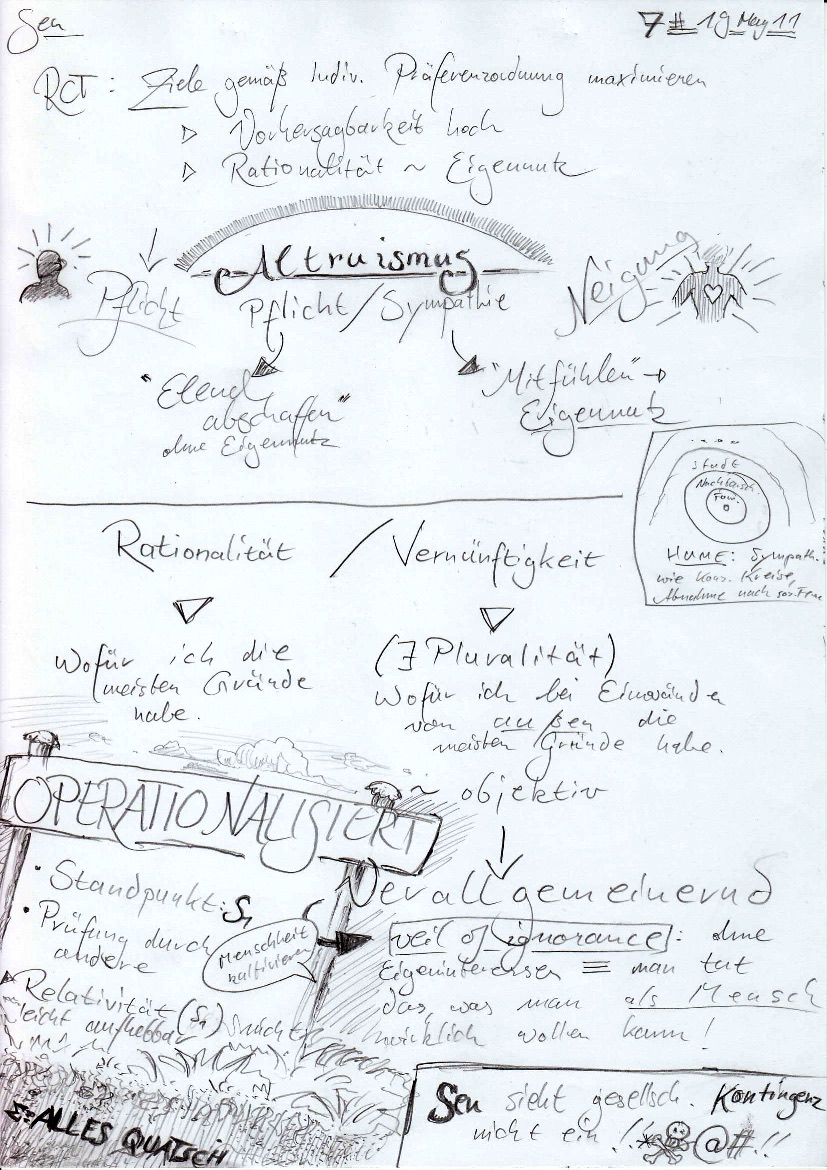

Take Notes on Paper (but Write at Your Computer)

I a recent radio interview, psychology graduate student Pam Mueller told the audience that taking notes of meetings or during class on your computer is a bad idea. You forget the things faster.

Plus you can’t sketch anything quickly when you’re using a computer.

Over the years at university, I adopted notes which were highly visual in style, not unlike Sketchnotes which I heard of many years later.

As we’re telling students in our coaching at my part-time job at university, it’s always better for your brain to add another layer of information: space, color, image, sound, smell, story. I think that’s why hand-written notes work better: you claim the space on paper in a unique manner. Even if you don’t add many visuals.

Using a computer or tablet or phone to type words requires you to be in a different mindset than writing with pen in hand. That’s why Sascha and I advise everyone to take reading notes on paper first. The gap between paper-based reading notes and the book or article you’re reading is smaller, even if you read on a digital device. Typing will always be more challenging, and switching back and forth will ruin your focus.

So take notes on paper, but write on your computer, since you’ll be about twice as fast to finish a first draft and produce more during the process.

Dominique Renauld on Fond Memories of Working on Paper

Dominique Renauld remembers when he was a student and worked exclusively with paper notes. He was fond of Roland Barthes1 and grew even fonder of Arno Schmidt – both avid Zettelkasten users.

Nowadays, Dominique uses Tinderbox for anything. Check out the slides and video of his post to see what working with Tinderbox can look like.

We can learn to be playful with our items of knowledge. We only have to think about what we would do if the knowledge was organized on paper. Tinderbox is a great application to work visually, although I haven’t tested it seriously, yet. If your app doesn’t support any visualization, simply start to draw diagrams. With a playful attitude, you could re-phrase existing notes, read and think about them, then write down your thoughts again.

It doesn’t suffice to feed new stuff your Zettelkasten. You have to attend to its needs, too. The result will be stronger cross-connections.

-

When Barthes lost his mother, he took notes about the process of his grief. The collected fragments were published as a book. I always rejoice when an author uses “Zettelkasten” colloquially, which isn’t too uncommon in German; and then I wonder why no one at university takes this method seriously. (The German source says: “Tatsächlich könnte man das Buch viel eher als einen geordneten Zettelkasten oder eine pedantisch geführte Materialsammlung bezeichnen. Tag für Tag wurde dieses Archiv der Trauer um neue Notizen erweitert, deren Kürze und Komposition oftmals an die von Barthes geliebten japanischen Haikus erinnert.”) ↩

Eco's 'How to Write a Thesis' Available in English

Finally, after being in print for 38 years in other languages, How to Write a Thesis by Umberto Eco is now available in English!1

I have mentioned the German translation of Eco’s book in the past already (in “Collector’s Fallacy” and “Making Proper Marks in Books”). From his book did I learn that not all Zettel are created equal. If you worked solely with index cards in the 70s, all this mattered a lot.

Remember that it’s possible to have a Zettelkasten without a computer. If you work on paper, you’ll be slow as heck. But you’ll still be more productive than all the other folks not thinking twice about proper knowledge management. Eco’s workflow details will help tremendously if you don’t know how to work with the tools available.

Nowadays, we have reference manager software, note-taking software, PDF annotation software, and whatnot. We tend to think in terms of our tools. But this veils our understanding of the ideas we work with, the texts we read. If we managed everything with index cards (but in different boxes), it’d be easier to look behind the How and see the What instead. Paper is almost never feature-bloated. Software makes it harder, because you can always get stuck at the surface level, switching apps all the time and looking for the next great feature. (Note the book isn’t called What to Write a Thesis With.)

If you care for non-fiction scholarly writing, if you’re a student, or if you’re just trying to figure out what kinds of Zettel notes there are and where they come from – pick up the book! It’s an educational read, but keep in mind most of the tips are outdated since personal computers exist.

(via Manfred of Taking Note; cover image © 2015 The MIT Press)

-

Affiliate link. You buy from this link, and we get a small kickback from amazon. No additional cost for you. ↩

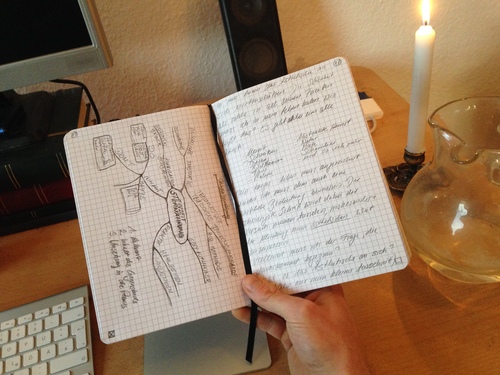

Use a Real Notebook

Considering the tech-heavy approach to knowledge work most people advocate nowadays, the imperative to use a real notebook may sound a little bit strange. But I am dead serious. The search for the perfect software application is one of the distractions which prevent you from stepping back and seeing the whole of your system. You are part of it, and each of your characteristic idiosyncrasies too.

Use a Short Knowledge Cycle to Keep Your Cool

It’s important to manage working time. Managing to-do lists is just one part of the equation to getting things done when it comes to immersive creative work where we need to make progress for a long time to complete the project. To ensure we make steady progress, we need to stay on track and handle interruptions and breaks well. A short Knowledge Cycle will help to get a full slice of work done multiple times a day, from research to writing. This will help staying afloat and not drown in tasks.

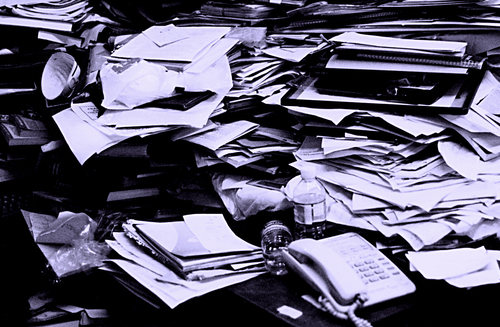

The Collector’s Fallacy

There’s a tendency in all of us to gather useful stuff and feel good about it. To collect is a reward in itself. As knowledge workers, we’re inclined to look for the next groundbreaking thought, for intellectual stimulation: we pile up promising books and articles, and we store half the internet as bookmarks, just so we get the feeling of being on the cutting edge.