The Complete Guide to Atomic Note-Taking

Atomic note-taking is one of the buzzwords surrounding the Zettelkasten Method. In short, it is about putting one idea and one idea only on a note.

With this guide, I will take you into the exciting deep waters of both the Zettelkasten and thinking skills. Having read this article, you will both know the theory and the practice, the art and the science of atomic note-taking.

This guide is created with progressively more depth:

- Why care? We will start by giving you good reasons to care about atomicity. Atomicity is not just a gimmick specific to the Zettelkasten. Atomicity is good thinking manifesting in your notes.

- Deep Understanding. We will dive into the four levels of atomicity, from surface level understanding to deep knowledge.

- Complete explanation. We will then explore the definitive answer to what atomicity actually is.

- Atomisation of ideas. We will examine atomicity as a process and its practical application. I will give you video demonstrations and commentary on how atomicity as a process looks in action.

- Atomic Note-Taking. We will learn how to take atomic notes right away. I will demonstrate this more in videos.

- Atomic Thinking. We will explore the connection between atomicity and thinking skills.

Why Should You Care About Atomicity?

Understanding Atomicity will help you with the Zettelkasten Method. I deem atomicity as integral to the Zettelkasten Method. The Zettelkasten Method is about creating links. The very idea of links implies that there are components that you link. The logical conclusion is to find the right scope for these components. The right scope is the atomic idea if your goal is to use your Zettelkasten to build knowledge.

Understanding Atomicity will help you understand the nature of knowledge. There is a lot to know about knowledge and the various methods to build and work with it. Knowledge work is a craft. You can learn it and you can train it.

Understanding Atomicity will make you a better thinker. The atomic idea is the destination that you want to arrive at in your thinking journey. The concept of the idea atom gives you a goal post, an orientation for your thinking. Atomicity is a concept that brings you into contact with the material of thinking, since we are talking about the atomicity of ideas. I define thinking as the process; thoughts are frozen processes, and ideas are the result of thinking.

Let’s dive now from the tip of the iceberg into the depths of understanding.

Levels of Atomicity

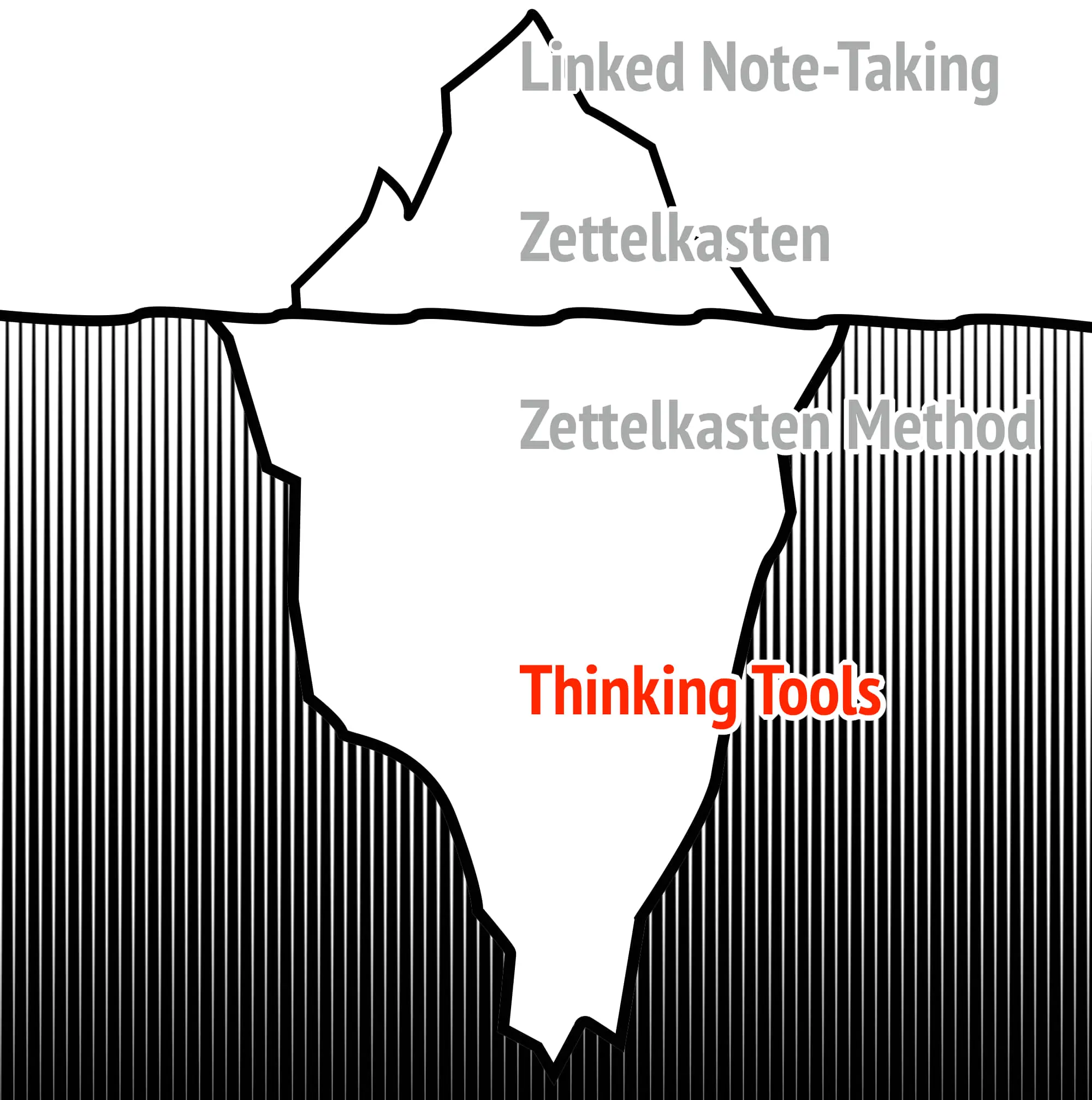

We will use the Zettelkasten Iceberg to provide you with a progressively deeper understanding of this principle. We will start by completing a surface-level understanding that addresses merely a way of note-taking and arrive at the deepest level, the nature of knowledge and thinking itself.

Here is the breakdown of the levels that we will descend to:

- Linked note-taking. Linked note-taking stands for the insight that knowledge and notes are about connections. Connecting ideas is what we need to do to gain insights and create new knowledge. So, why not start by creating connected notes?

- The Zettelkasten. The Zettelkasten answers the question where to put all these connected notes. The process of adding notes to the Zettelkasten is facilitated by a workflow, a series of steps that result in linked notes.

- The Zettelkasten Method. The Zettelkasten Method is a label for a deeper and more informed perspective on how to use the Zettelkasten to solve methodological problems like the problem of scope (“How to create a Zettelkasten that works with the total of the notes I will take for the rest of my life?”) or time (“How do I record my ideas, so they are valuable in even a decade?”).

- Thinking and Knowledge.1 The Zettelkasten Method provides a thinking environment to empower you to think in support of your past thinking efforts. Our goal is not to create a Zettelkasten or to adhere to the orthodoxy of the Zettelkasten Method. Our goal is to think and create knowledge.

Let’s start.

Level 1: Atomicity and Linked Note-Taking

Atomicity doesn’t play a particular role on the level of linked note-taking. There is some notion about the size of each note. Richard Griffiths has a particular pragmatic and smart way of saying “Don’t make a fuss about it.”

An atomic note, for me, is the shortest writing session that could possibly be useful.

So, on this level, atomicity is about reaching a threshold that gives you, the note-taker, value out of the act of taking the note.

Creating a personal wiki is another effective way to take notes. Here, you don’t care about atomicity at all. If the wiki is about collaborative writing with others, a personal wiki could be seen as collaborative writing with yourself.

The problems that are solved on this level are:

- Storage

- Access (via full text search or hub pages) and centralisation of access (one place to access your knowledge)

- Incremental growth of the personal note-base

According to Tiago Forte’s BASB approach, one could even argue that delaying to process ideas as much as possible can be seen as a success. Why would you invest time and energy into processing ideas just in case? This is a reaction to the modern problem of overabundance of information, and it works very nicely. I, myself, organise a lot of my input via my Rumen (my name for my second brain). The minimalist structure and the limited rules of BASB make perfect sense if your goal is to create access to material (everything from your own ideas to saved PDFs), organised for actionability. But the approach reinforces the position that, on this level, atomicity doesn’t count. Perhaps, even stronger: Atomicity is an unnecessary complication.

If you care about storing a mix of personal notes, notations on texts, excerpts, PDFs, and the like, you don’t have to think about atomicity at all. Just keep in mind that you may avoid the challenge of atomicity, but you also limit the power of your note-taking system. With your Rumen, you get all kinds of material organised for their actionability. But that’s it.

You advance from level 1 to level 2 by caring about guidelines on how to manage and interact with your notes.

Level 2: Atomicity and the Zettelkasten

Two decisions are made to create a Zettelkasten:

- You create a container for your own notes. That excludes storing PDFs in your Zettelkasten, for example.

- You think about what makes a note a Zettelkasten note.

Let’s focus on the second decision and explore possible answers to the problem of determining the characteristics of a proper Zettelkasten note.

Atomic notes are the result of a workflow. One answer to the question of what makes a note in your Zettelkasten is provided by the workflow. In Ahrensian terms: You create fleeting and literature notes. Out of these notes, you create “main notes”, which are then the “proper” notes in your Zettelkasten.

However, the workflow fails to address the necessary characteristics of what makes a Zettelkasten note proper.

Atomic notes are short notes. This is a false dichotomy, conflating brevity with atomicity: a fallacy that assumes one extreme is true if the opposite isn’t. Just because atomic notes are not wiki pages or essays doesn’t mean that atomicity is achieved by simply choosing the opposite extreme of making notes short.

Atomic notes are notes that contain a single idea. If you have no idea what an idea is, this sentence doesn’t mean anything. It merely gives you an illusion of understanding, because to make this sentence actually meaningful, you need to know what an idea is. Everybody Talks About Atomicity, Nobody Ain’t Talking About the Atoms.

The notion that atomic notes contain one idea is not an explanation, but the avoidance of an answer. It merely transforms one underdetermined statement into another. Imagine you ask me, “What is a cat?” and I answer, “It’s like a dog.” The only way you can make sense of my answer is when you know what a dog is.

BUT:

There are useful heuristics that point in the right direction. I will pull some examples from one video by the famous Morgan.

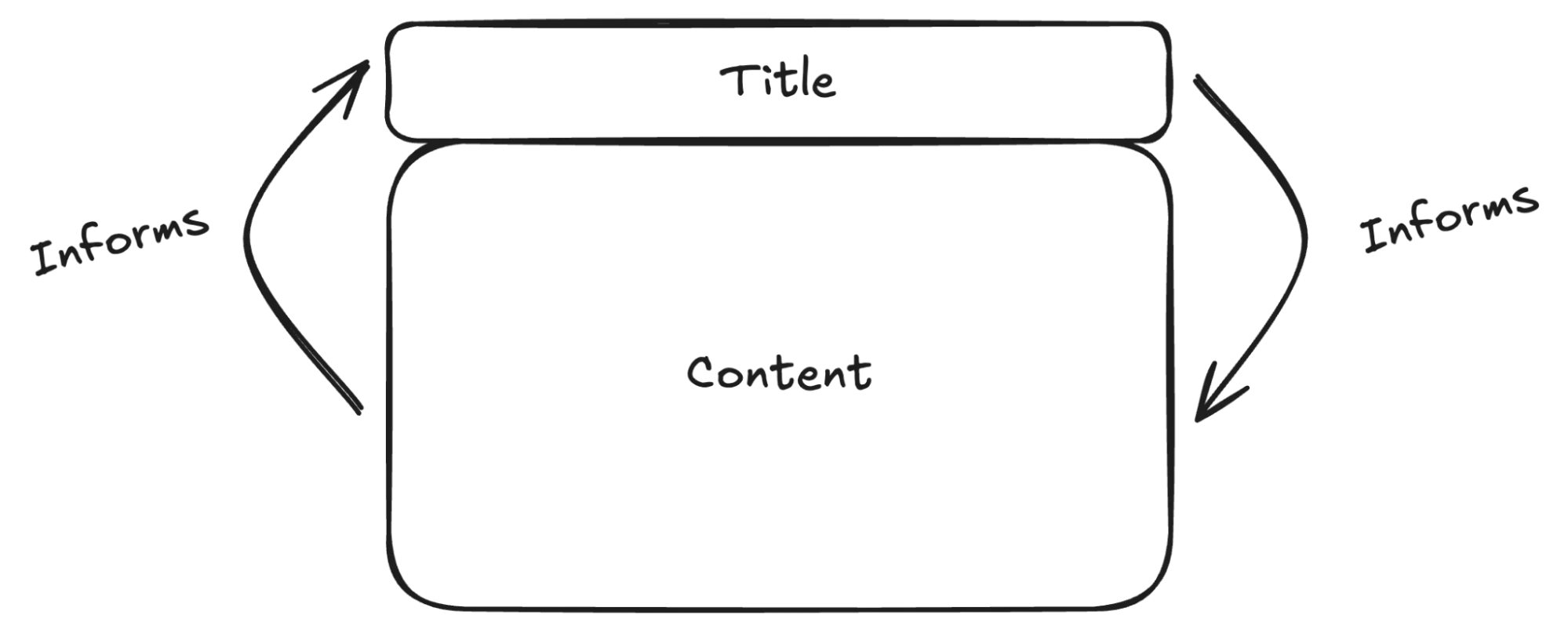

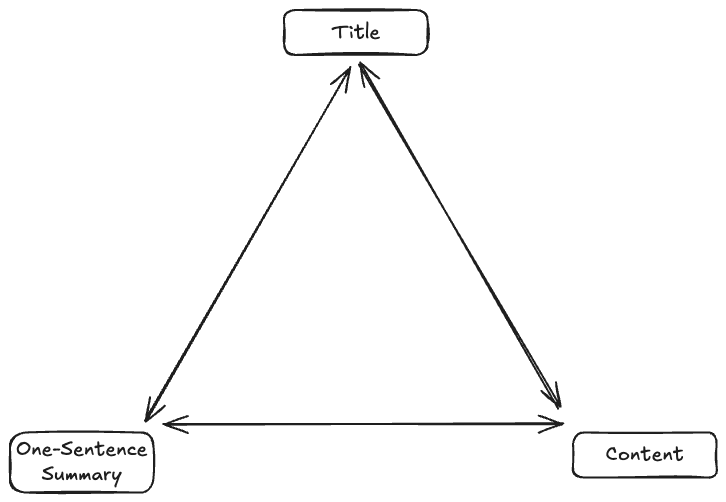

- A note is fairly atomic if it is easy to name. The more you approach the atom, the essence of the idea, the better you understand it. That means if you get to the essence, especially if you do it on paper or screen, the note title presents itself more naturally. I called this interplay of note content and note title two-step compression, with the slight caveat that I put a one-sentence summary in the middle.

- It is understandable at a glance. This is again a very good, yet underestimated heuristic. We all know that we sometimes write down an idea, only to scratch our heads when we try to understand it even just a week later. Sometimes, it is because we wrote down an incomplete idea without a clear path on how to make it complete. The context of the original moment is lost, yet it shows that the context was necessary to understand the relevance, if not the essence, of the idea, and cannot be reconstructed. It goes both ways: Either the note’s idea is too complex or incomplete.

In her breakdown, Morgan puts a heavy emphasis on one direction: Reduction. This is why the following two heuristics in her video are “shortness” and “the inability to cut anything.” This is natural, since the point of reference is her lecture notes. She describes the process of breaking down long notes with a lot of ideas into atomic notes. In relation to lecture notes, an atomic note is indeed short. Compared to a note scribbled in a book’s margin, an atomic note is longer. The shortness of the note is a relative quality. So, you can’t absolutely say that a Zettelkasten note is either short or long. It depends on your point of reference.

What is missing, however, is the possibility of incomplete ideas. In the extreme case, lecture notes that only contain incomplete ideas and therefore need to be built up instead of being broken down.2

This second level is a no-man’s land that you must pass through, but shouldn’t settle in. Let’s dive deeper.

Level 3: Atomicity and the Zettelkasten Method

Now, we are below the surface of the Zettelkasten Iceberg. Think of the difference between above-the-surface and below-the-surface as the difference between making educated guesses about what you assume is below and actually going below the surface to engage with the thing you previously assumed.

Think about the difference between a fisherman and a scuba diver:

The fisherman has very efficient heuristics about what is happening in the water. A scuba diver can go in there and see for himself. The scuba diver has a much clearer picture of what is going on because he is in direct contact with the object of interest, rather than interacting with a black box.

This is what we have to do to navigate this level of depth. We have to get into direct contact with ideas. I got into direct contact in 2011 and published a bit of it in 2016 under the title Reading for the Zettelkasten Is Searching.

What I did was to build an inventory of knowledge building blocks for which I had a sufficient understanding, so that I would know their wholes, parts, and the parts’ relationships. To this date, the inventory is stable. I didn’t have to add or remove any items from this inventory, and it holds up even though both my work and my clients cover a wide range of topics.

If you want to master the building blocks, the raw material of the knowledge that you want to build, you have to examine the building blocks closely. You have to choose to become a scuba diver if you want to learn what is below the surface.

As a reminder, Level 3 originates from Level 2 because the problems are not solvable by Level 2 thinking. I cannot resist the cliché quote:

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

—Albert Einstein

One of the major benefits that comes from merely applying the organisational aspects of the Zettelkasten Method, like tagging, choosing a good title, writing a one-sentence summary, linking with context, and the like, is that they force metacognition on you. You have to observe your past thinking and make a judgment. The power of Morgan’s heuristic, which suggests that an atomic note is easy to title, stems from this heuristic being a metacognitive thinking step.

To master this level, you have to put in the effort. Heuristics allow you to avoid effort and save time and resources, while still arriving at a good-enough conclusion with incomplete evidence. But they have limits, especially if they are not backed up by the ability to also think about the issue the hard way. We all know the situation in which the expert says, “Just make sure that [INSERT HEURISTIC]”, we focused on that, only to fail, and report to the expert, who then replies, “Well, in that case [INSERT ANOTHER HEURISTIC]”.

Do you need to master this level? Well, this depends on how much skill you need and want to develop in knowledge work. It also depends on how difficult the topic is for you to think about. However, since you are reading this article, it’s likely that you both need and want to master this level of knowledge work.

Now, let’s descend to the deepest layer of the Zettelkasten iceberg.

Level 4: Atomicity, Thinking, and Knowledge

Regarding levels 1 and 2, most people appreciate the respective advice and feel that it is helpful. This is completely natural. The words of advice are:

Level 1: Don’t sweat it.

Level 2: Here are easy-to-understand heuristics, saving time and energy, giving you good-enough results.

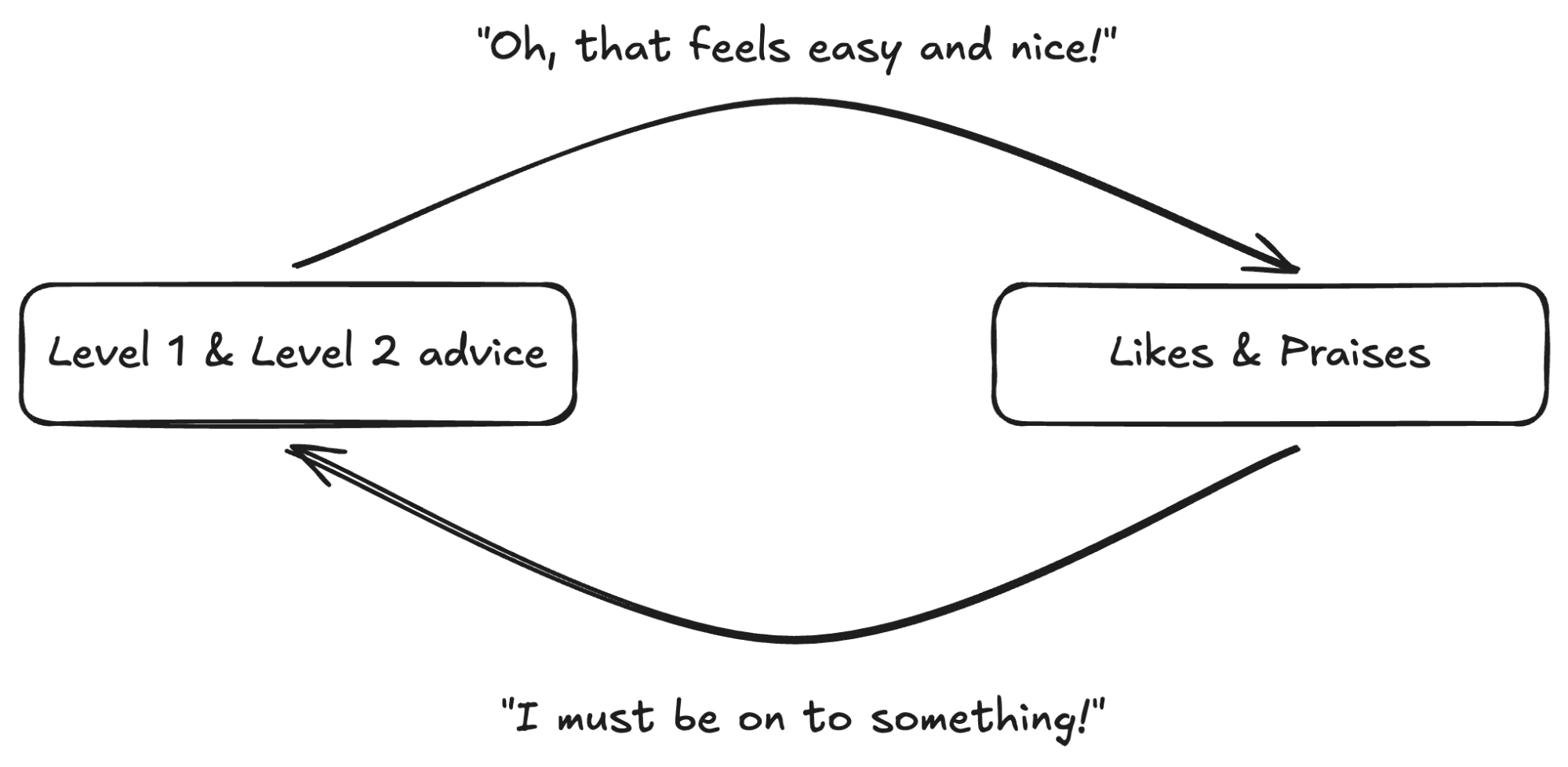

With that, a positive feedback loop for content creators and content consumers is established:

Both parties are happy. The consumers get relief and comfort. The content creators get positive feedback, likes, shares, and comments. However, they both tend to get stuck in their journey on this level, never crossing the threshold where the magic starts to happen.

Level 3 is where a lot of people put up resistance: they either claim that this is entirely unnecessary (heuristics are good enough) or complain that I make concepts more complicated than they should be. This is also natural and completely rational. If you are conditioned by the positive feedback loop mentioned above and someone tells you to invest time and energy, it appears as if someone wants to take the ease you have acquired from you.

In addition, with this feedback loop established, you get several biases into play:

- The fluency heuristic that makes us assign more value and believe that it is more likely to be true if you can process the information more easily. Levels 1 and 2 are easy to understand compared to level 3.

- The mere-exposure effect that makes us like things more with repeated exposure. Levels 1 and 2 are currently the only levels presented to date, leading to the misconception that they are all there is to atomicity.

- Applying levels 1 and 2 makes way for the overconfidence effect. By merely applying surface-level thinking frameworks, we can prolong the wrong impression of mastery over the material we process. To me, this is one of the most painful, yet strangely rewarding aspects of going to level 3. All too often, I was confident in my mastery level of a particular idea, only to be rudely awakened by my own ignorance when I actually attended to objective and formal criteria.

I don’t want to get into the full in-depth psychology of knowledge work and communication. But just from this small number of examples, you can see how this feedback loop creates problems.

As a last pointer to the problem: relying on heuristics and workflows to get to atomic notes means that you externalise the expertise to an outside source. Ford once did this: The assembly line was created, so the low-skilled worker could contribute to a high-end product. The skill and expertise were no longer found in the individual worker, but in the process. Economically, this reduced the bargaining power of the working class, since each worker was more replaceable.

Relying on the expertise of a system means that you try to create a high-end product without being skilled yourself. Taken to the extreme, this would mean that you’d just follow the method, and a book would be written “effortlessly”. This approach is doomed to fail. You may read this story as an illustration.

So, we’ve established levels 1 and 2 as the no-man’s lands of understanding. Now what is happening on level 3? Again, we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them. The solution to the problem of level 3 lies in level 4.

Let’s think about what is implied by the advice to make a note atomic.

- An atomic note contains one idea.

- An atomic note contains one idea if you can’t remove something from the note without rendering the idea incomplete, and if nothing is missing from this idea.

In other words:

Get to the essence of the idea.

Does this look like Zettelkasten-specific advice to you? It doesn’t to me. It is a principle for good thinking. Now, let’s put the first three levels in other words, according to this advice.

Level 1: Don’t sweat getting to the essence of the idea.

Level 2: Use these simple and easy heuristics to indirectly assume that you got to the essence of the idea.

Level 3: This is how you make sure that you get to the essence of the idea, but you have to put in the work.

Which one is advice to bring you A-game to the thinking challenge?

Level 4 is reached when you see that level 3 is actually about sound thinking and not some methodological gimmick. If you want to become a deep and skillful thinker, you should not only reach level 4 but truly embrace it. Unleash the full power of your thinking tools on the thinking challenge at hand.

Now, let’s take atomicity seriously and explore the fundamental building blocks of knowledge.

What is Atomicity?

If we assume that the principle of atomicity means that we should aim to arrive at one note containing only one idea, the question has to be answered by defining what an idea is.

My approach is to build an inventory of knowledge building blocks. My claim is that knowledge is organised in discrete building blocks that serve a specific function. Here is my inventory:3

- Concepts define a specific part of the world. You draw a boundary and say, “This is X.”

- Arguments transfer the truth of a set of statements to another via a logical structure.

- Counter-arguments disrupt the transfer of truth provided by arguments.

- Models relate entities to each other and provide part-to-part relationships and part-to-whole relationships, often to map a part of reality or a fictional reality.

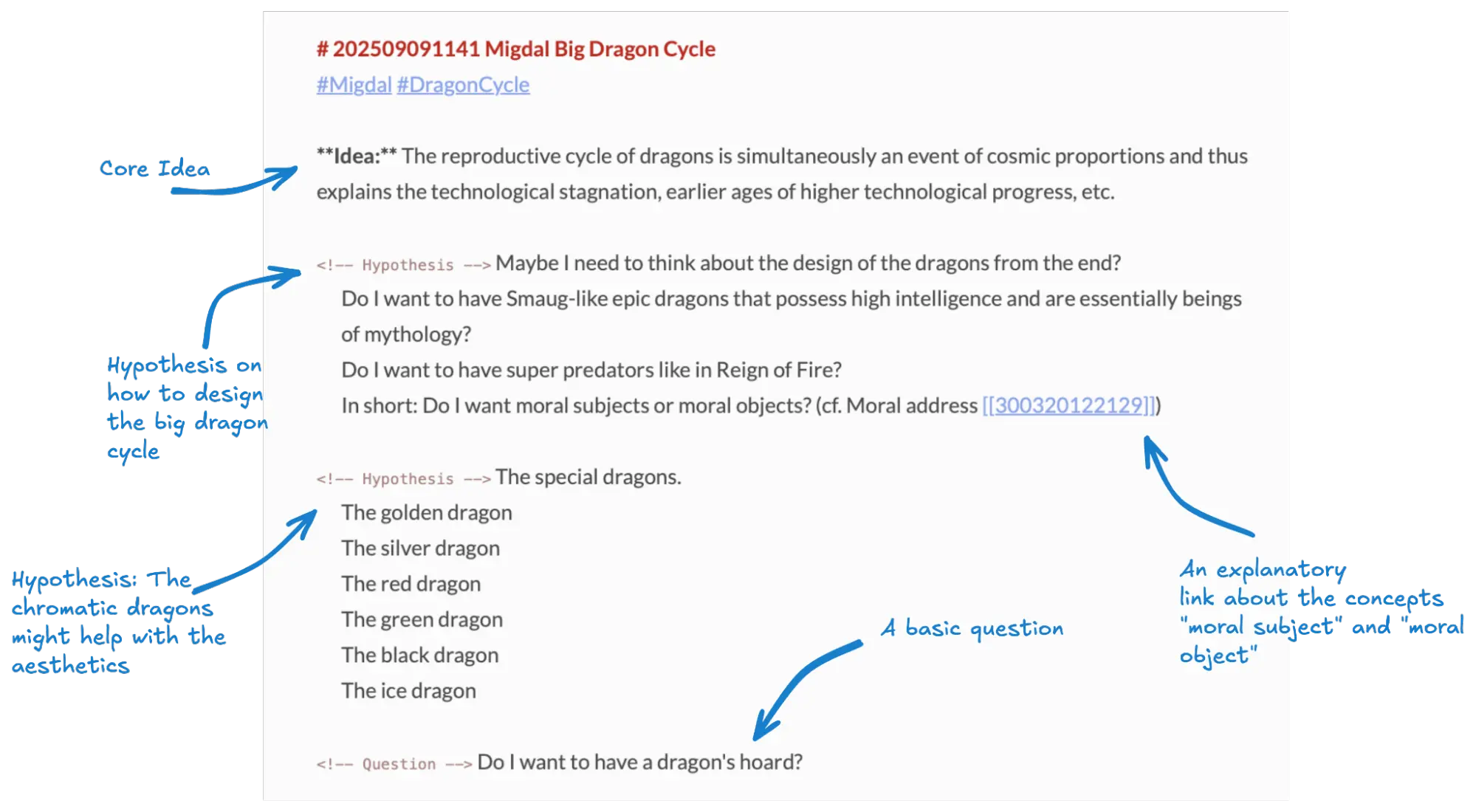

- Hypotheses and theories formulate statements on how reality actually is. The difference is that a hypothesis is an isolated statement, while a theory comes with an inventory of methods.

- Empirical observations are results of sensory probing on how reality actually is.

Purely atomic notes are notes that contain exactly one knowledge building block.

Equipped with this inventory, it is simple, yet often hard to move from atomicity level 2 to level 3: You identify the knowledge building block and make sure that you neither miss any part, nor put anything unrelated in the note. The formality often requires a significant amount of effort from you. Yet, it is more than worth it: The boon is complete mastery of the idea.

There are supporting concepts that help to understand the principle of atomicity. These supporting concepts should help to soften the perspective. Some people treat atomicity not as a principle but as the law that no Zettelkasten note shall bear more than a single atom!

First, sound communication with your future self. If you start dividing content into different notes just because it makes the notes atomic, while sacrificing the usability of your notes, you set the wrong priorities. The usability of your notes is obviously more important than orthodoxy. This is especially true in the earlier stages of a note’s maturation.

Keep in mind that atomicity is an intended outcome. In Nori’s last coaching session, I gave her this advice: Treat the problem, solution pairing as the idea that you keep on this note, even if each solution might be worthy of its own note at some point. If you work on a solution, it is often wise to keep everything on one note. Your future self wants everything to be available with a single glance. It doesn’t want to be burdened by a lot of clicking and link-following.

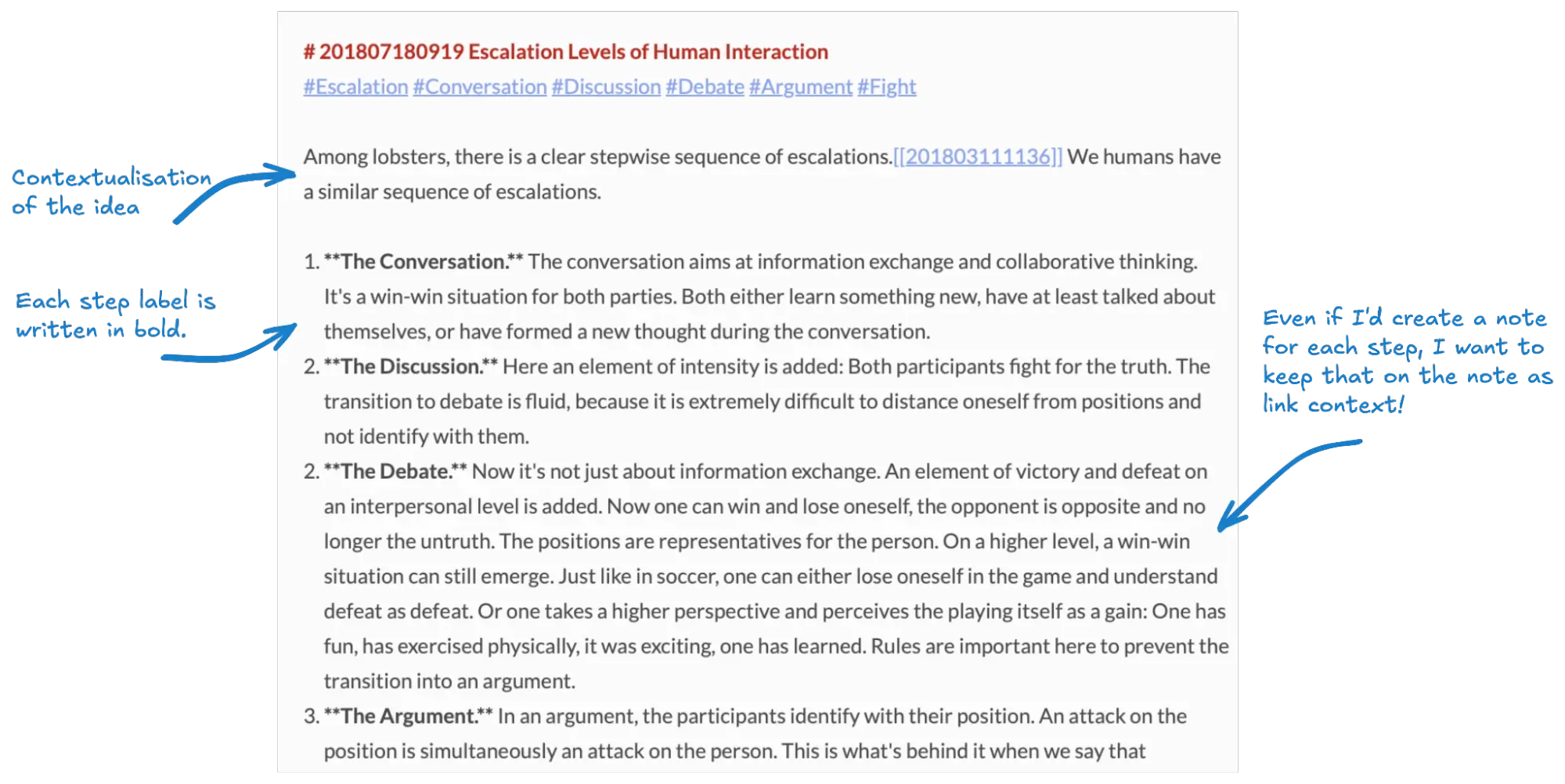

Another example is an idea that is on the border of developing into a structure note. Let’s say that you start with a concept. You then explore each aspect of the concept. The notes expand, and the knowledge building block morphs into a model. Typically, you need some description of each element that you explore deeper on its own note. So, technically, the note is not purely atomic anymore if you treat each element description as its own knowledge building block. However, your future self benefits from a clearer description and, therefore, extensive link context.

Second, the focus of the note. This term comes from Bianca Pareira. She compares a note to a photograph. You focus on one object, but that doesn’t mean there is nothing but this object in the photograph. Instead, you have a background that is actually needed to contextualise the object in focus.

In light of this concept, the focus of the sample note above is on the escalation ladder of human conflict, while the details of each stage are presented in the background of the note. This example also illustrates that the concept of one focus object per note doesn’t allow a superficial heuristic, such as: The majority of words should be dedicated to the focus. Sometimes, a note has a narrow focus that is contextualised extensively. Technically, the reason is that the concept of focus is on the same level of analysis as knowledge, which cannot be quantified in terms of the number of words. This notion rhymes with the notion that idea atoms come in different sizes, rejecting the heuristic that an atomic note should be small. Hydrogen and Plutonium are both atoms, yet of very different size.

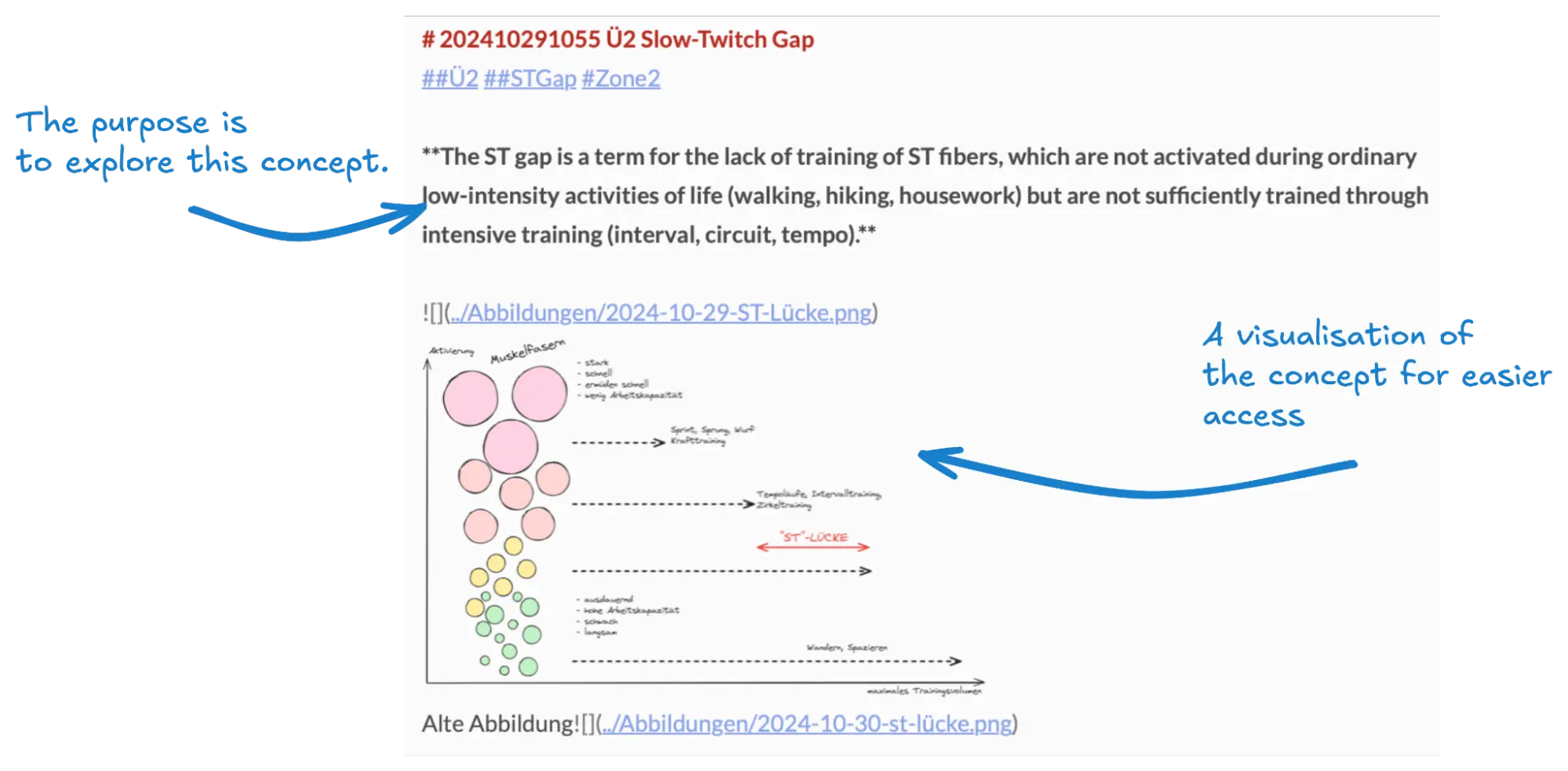

Third, the purpose of the note. The purpose of the note can be a lot of things, and it dictates what might be in the backdrop out of focus. More importantly, the concept of purpose highlights a connection between structure notes and atomic notes. The purpose of an atomic note is to zero in and create a close-up of an idea. The purpose of a structure note is to provide a higher-level view. Some structure notes are about a single idea. I have, for example, a structure note about the “slow-twitch gap”. It is about a particular gap that is present in many training programs. It may be about a single idea, yet the purpose is to give me an entry point to a small area of my Zettelkasten through the lens of this idea. Other structure notes are about providing access to topics, or act as thinking canvases. But still, there is a single purpose for each structure note.

What is atomicity, then?

Atomicity refers to the idea that knowledge is made up of discrete building blocks. The Principle of Atomicity is a processing direction in note-taking, aiming for one knowledge building block per note. It is not a rigid law, but a guiding compass. It needs to be contextualised for each application.

The Principle of Atomicity marries the Zettelkasten Method with principles of sound thinking. Following it is a pledge to aim for depth and to push beyond surface-level understanding.

Note-taking is no longer a chore. It becomes a discipline. Each atomic note is a training session for the craftsmanship of knowledge, bringing you one step closer to mastering knowledge craftsmanship.

Critical thinking skill is the ability to analyse available observations, evidence, and arguments to form reasonable judgments. A key element of critical thinking is to identify and evaluate empirical observations, arguments and counterarguments. That means that three out of the six knowledge building blocks are essential to master for critical thinking and, therefore, being able to make reasonable judgments.

Systems thinking skill is the ability to analyse and make sense of systems, especially complex systems. Systems are specific models. A stock-flow model is a method for modeling a system, for example.

Both of these thinking skills are based on your ability to identify key concepts, empirical observations, arguments, counterarguments, hypotheses and models. Mastering atomicity goes hand in hand with mastering basic levels of critical thinking and systems thinking.

What about unfinished notes?

Let’s think about the relationship between thinking and ideas: Thinking is the action we perform with our minds. We want to arrive at ideas. We want to form an argument, find the solution to a problem, and understand the pattern of a historical event. There is a process and a result that we aim to achieve. I call the process thinking and the result the idea. If we don’t arrive at the idea, we are not finished thinking. The concept of an idea rests on the premise that we can arrive at something with our thinking.

In this framework, a note has different maturation stages:

- Thinking Stage. You’re in the process of writing the note.

- Finished Thought Stage. You finished writing the note.

- Idea Stage. You edited the note, so the note contains an idea that you can identify.

To mature your note, you’ll need to write it, complete the note, and refine it until you have clearly identified the idea.

There is no rule about the timeline when a note has to mature. You can start recording your thinking in your 20s, continue through your 30s, complete your first draft in your 40s, refine it through your 50s, and finally bring the idea to fruition in your 60s. Is this too outlandish for your taste? What about starting to write in the evening, being interrupted, and finishing the note the next morning? This is a perfectly normal development: otherwise, we’d have to assume that while we slept, our Zettelkasten was in an impure state, that leaving it in the evening breached protocol, and that it returned to purity only the next morning when we finished the note. I think that’s ridiculous.

My advice is to move the complete maturation process into the Zettelkasten. If the Zettelkasten is an integrated thinking environment, it should

- Facilitate thinking

- Allow you to take a snapshot of your thinking, and observe it

- Capture individual ideas as building blocks for future efforts

To truly make the Zettelkasten the environment in which this process happens, you have to move your thinking into your Zettelkasten right from the start. Consequently, the Zettelkasten will contain half-finished ideas, and stuff that’s not thought through to its final conclusion. But forbidding the existence of these artifacts would prevent ever reaching the perfect future of fully-formed, thought-through ideas.

If you have the impulse to record an idea, create a note. This will turn your Zettelkasten into a home for your mind and thinking. To make this happen, you have to accept that your Zettelkasten will reflect the various stages of the maturity of your thinking.

The only thing that you have to take care of is that you make it obvious for your future self how to continue. One technique is to capture the possible ways to develop the idea.

The above idea is still in progress, a tiny little puppy that has a lot of growing to do. I kept all the mistakes in the note so that you can see an immature note.

How To Take Atomic Notes

This is why I emphasise that atomicity should be understood as the goal to achieve, instead of the condition a note has to meet to be in your Zettelkasten. It allows you to work on the appropriate level of atomicity. Not all ideas should be met with the same investment.

Step 1: If you enter a new idea, focus on creating the note without hesitation or doubt.

In the beginning, there are no rules. Freely write down the idea in your own words. Write with atomicity in the back of your mind, not with the focus. You can always clean up your notes later on. Don’t let yourself be paralysed by the idea of needing atomicity before you write notes.

If you are a writer, this advice should look familiar. When you write, the goal is to avoid editing at all costs. Otherwise, you start to stand in your own way, reducing your productivity and creativity. In the most extreme cases, you can get stuck in writer’s block.

The same is true for quite many people when they try to create atomic notes. They no longer write out their thoughts freely. Adding something to your Zettelkasten can become tedious and unpleasant.

Ignore every rule when you enter a new idea! Just let your thinking flow through your fingers onto the screen and see what happens. The flow of free writing is meant for you if you work with your Zettelkasten.

Step 2: If you have finished freely writing your mind, evaluate your ideas using a couple of heuristics.

Now it’s time for rough editing. You don’t edit to make the text more pleasing to read. You edit to understand what you’ve produced. This is a part of the process, similar to traditional writing. All too often, we don’t write down what we’ve already figured out in our minds, but instead discover new ideas through our writing.

A lot of the surprising new ideas that are born through working with your Zettelkasten are born through this mechanism, by getting into the flow and letting the inspiration work through you.

Work on the content of the note on the basics of heuristics:

- Can you understand the idea at first glance?

- Can you easily title the note?

- Which elements can be removed without detracting from the idea?

- What needs to be added so the idea stands on its own?

To me, another heuristic is crucial and marks the threshold of a proper Zettelkasten note:

If you had to work with that idea, do you know what would be next?

This doesn’t mean that you should already have a plan ready to be executed. Intuition is enough. Put yourself in the shoes of your future self. Your future self wants to be exposed to forward momentum. That means that it needs ideas that speak to it. If the idea doesn’t resonate with you now, chances are that your future self won’t like it either.

Executing idea development to this threshold is dependent on a paradigm change:

Don’t ask yourself how to improve your life right now. Ask yourself how to improve your future instead.

Typically, people that are interested in note-taking ask themselves how they can improve their situation now. They want to be more efficient, want to automate, reduce the fear of missing out, and feel more confident today. That can put you into conflict with your future self, because it often means avoiding work now that your future self will then have to do.

The major paradigm shift from ordinary note-taking to the Zettelkasten Method is that you shift the focus from solving current problems to working for your future self. The Zettelkasten Method promises to help you effectively improve the situation of your future self. Since the present is just a tiny moment between the vast past and the infinite future, it doesn’t make sense to take away from the future to improve the present. With a present focus, you can only enhance a tiny slice of your life, and you have to work constantly to keep the improvement. If you can set up a structure that by itself continually improves your future, each moment in the future, which will be the very present that you are experiencing, will benefit from this setup.

This is another source of resistance against the Zettelkasten Method. Many people seek out methods to solve problems in the present. They are naturally attracted to solutions that make “it easy and effortless”. Influencers will see this demand and create content to satisfy it. Don’t let those false promises fool you. Getting to the essence of an idea is hard.

The second brain approach is about avoiding early commitment. The Zettelkasten Method asks you to lean in, actively engage with the source, extract the ideas, carefully capture them in notes, and connect them to your body of knowledge.

I use both for the very reason that the second brain is protecting my time, energy, and attention, so I can lean in and fully engage with the sources as much as possible. This pattern is a universal pattern of protecting my mental resources and focusing them there, where I feel the most potential for my work and life:

- The Barbell Method of Reading is about combining superficial, fast reading with intense, slow, and deep processing, only reserved for the best parts of each source.

- The combination of the second brain and the Zettelkasten Method is about avoiding investment into most of the sources, so I can focus on the sources that are the most valuable.

- The approach to atomicity as a process is to constantly be exposed to deep knowledge work opportunities by lowering the barrier of entry and letting the idea at hand prove itself worthy of my time, energy, and attention.

But I can’t be constantly conscious of applying this strategy. This would divert mental resources away from the task at hand. Instead, this strategy is part of the system and the workflow.

Often, working on the title is a back-and-forth between editing the title and the note. You come up with a title that gives you a different perspective, so you edit the note’s content, which necessitates a better title, and so on. A feedback loop of self-reinforcing idea improvement is established.

If you create a one-sentence summary, you have an additional force that helps you to improve the idea.

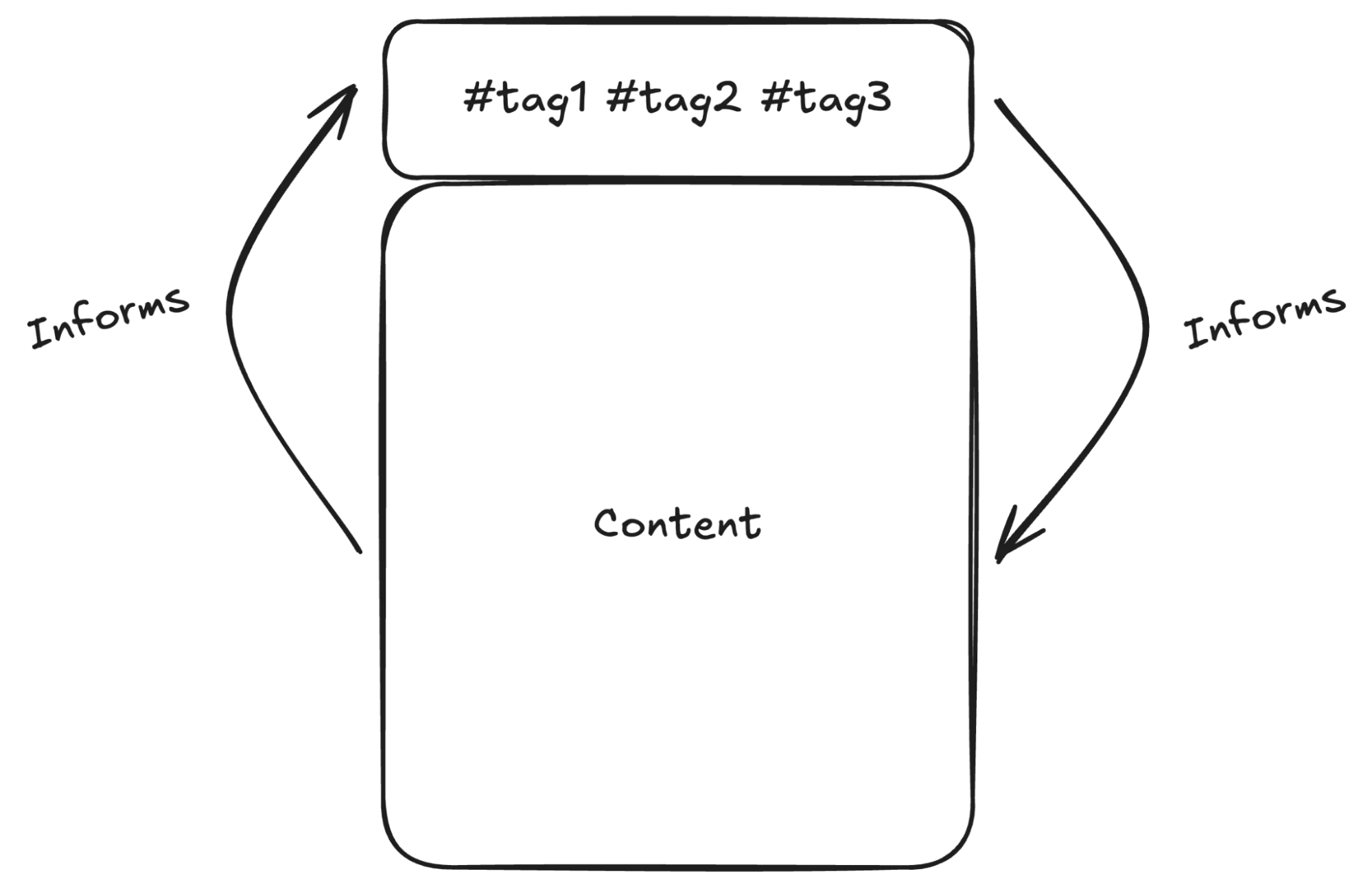

If you use object tags (highly recommended), you have to figure out what the most essential concepts of the idea are. In a way, you delve into the subatomic level and identify the critical components of the idea. Another self-reinforcing feedback loop is now helping you to improve the idea.4

Step 3: You identify the knowledge building block.

Now, we dive under the surface. With step 2, we did a lot of cleaning up already. Next, we fully attack the task of getting to the essence of the idea. We don’t rely on intuition or heuristics anymore. We don’t guess, we make certain. When we are finished, there is no doubt left about what the essence of the idea is.

Are we dealing with an argument, a model, a theory, or an empirical observation?

If you identified the knowledge building block, there is no room for doubt anymore about the essence of the idea. You fully made the idea your own and mastered it. This confidence has to be earned. It is not given to you by any system or method. It is earned through hard work. But oh, the reward!

Step 4: Unleash the kraken.

Unleashing the kraken means that you start using your knowledge building methods to build upon the idea. A set of these methods are creative techniques.

In my domain, health and fitness, there is a concept known as the “RM-table”. It is basically a table that tells you how many repetitions you can perform at a given percentage of the weight that you can lift exactly one time:

| Maximum Repetitions | Percentage of your 1-rep-max |

|---|---|

| 1 | 100 |

| 2 | 95 |

| 3 | 93 |

| 4 | 90 |

| 5 | 87 |

| 6 | 85 |

| 7 | 83 |

| 8 | 80 |

| 9 | 77 |

| 10 | 75 |

This table is useful because it helps you determine the right starting weights when beginning a new training plan, serves as a tool for monitoring your progress throughout a training cycle, and allows you to track your improvement without needing to perform a maximal strength test, such as finding your one-repetition maximum.

This table should not be used as the gospel truth. There are a lot of nuances to it.

- This is the table based on an approximate convergence of a whole range of different calculation methods, deviating from them by only 0.5–2%. This makes it a good compromise between the usual methods of calculation.It assumes a linear relationship between repetitions and load, although in reality this relationship is nonlinear.5

- Calculated 1-rep max (1RM) is overestimated in exercises involving little muscle mass and underestimated in exercises involving a lot of muscle mass.6

- The calculated 1RM underestimates the actual 1RM for deadlifts more strongly than it does for squats.7

- The daily fluctuations might be as high as 10-20%.8

- …

Imagine you are a trainer. Imagine the confidence that you gain if you use this table and work in your review of two dozen specific studies, instead of looking up this table and taking it at face value.

The fourth and final step involves amassing details and perspectives. To be fair, this often takes you far beyond atomicity. The main difference between this step and the others is adding to the idea. In the example of the RM-table I chose, I conducted systematic research to gain insights into various details, which resulted in many footnotes, some of which you are seeing.

If you have read this article this far, you may ask yourself, ‘Who has time for this?’ The resistance that many people feel when they are asked to put so much effort into their notes is well-justified: our mental resources are precious.

Giving Ideas What They Deserve

Not all ideas are worthy of being fully developed. The truth is that you shouldn’t go all the way with every note. I developed a tier list of ideas in relation to their worthiness of full treatment.

| Tier | The Idea | What To Do With It |

|---|---|---|

| S | Major leap for your thinking, very likely to support a current and important project | Unleash the kraken |

| A | Improves your thinking, supports a current project, helps with future projects or areas of responsibility | Get at least to level 2, consider level 3 and 4 |

| B | Seems useful, a clear connection to an area of responsibility | Get to level 2 |

| C | Interesting, possible connection to an area of responsibility | Don’t sweat it, consider putting in your Rumen |

| D | Interesting, has some connection to your life | Put it somewhere, but not in your Zettelkasten, possibly your Rumen |

| F | Interesting | Nothing |

This tier list is not meant to be applied strictly. My goal is to give you an idea of how to think about the threshold of putting something in your Zettelkasten. Don’t put everything and anything in your Zettelkasten. It doesn’t work for read-later apps, and it definitely doesn’t work with your Zettelkasten. The Zettelkasten Method can’t compensate for a toxic information diet of careless consumption and collecting.

That doesn’t mean that you never have tier F notes in your Zettelkasten. Quite often, you will discover the tier while writing the note. You might start enthusiastic about an idea, but end up quite disappointed. One trap that many, including myself, fall into is the deepity trap. We read something seemingly profound, we want to process it, and yet we can’t make anything of it. We misjudged the quality of the idea. In the case of deepities, we were fooled. We may start with the expectation of releasing the kraken, but we get stuck on “meh”.

This is completely fine. Don’t delete the note or feel bad about it. It is part of the process. Perhaps you were wrong about being wrong, and the idea turns out to be super valuable. To me, this was the case when I read Seven Habits of Highly Effective People by Covey. After my first reading, I created zero notes afterward. A decade later, this book is a big pillar of my Zettelkasten departments on self-improvement and meaning work.

It is the same as in investing: The objective is to make rational decisions and have a system that takes the possibility of being wrong into account. This is why you never invest in just one company. You diversify. If some stock is down because of circumstances that you couldn’t foresee, you didn’t make a bad decision. You made a rational decision and happened to be wrong. The same is true with your Zettelkasten work. Based on your available information, you invest time, energy, and intention in the various ideas that you are working on, depending on the best available knowledge on the value of each idea.

Demonstrations on Atomic Note-Taking

Disclaimer: I tried my best to convey to you atomic note-taking in this video. It is a screencast with my commentary as a voice-over. For the sake of authenticity, I didn’t try any artificial application of a tool. Yet, I was constantly aware that I was performing for you, which took me out of flow. Keep that in mind when you watch this video:

Parting Words: Don’t Be an Atomicity Zealot, Be Atomicity-Informed

We started by asking why you should care about atomicity. The answer runs deeper than note-taking techniques or Zettelkasten orthodoxy. Atomicity is primarily about thinking clearly and skillfully working with the fundamental elements of knowledge.

We’ve descended through four levels of understanding: from the surface-level advice to “not sweat it” and rely on simple heuristics, down to the deepest level where atomicity reveals itself as mastery over knowledge building blocks: concepts, arguments, models, hypotheses, and empirical observations. Each level has its place, but only the deeper levels unlock the full potential of your thinking.

Atomicity is not a rigid law but a principle that guides you toward the essence of ideas. It’s the difference between being a fisherman who makes educated guesses about what lies beneath the surface and being a scuba diver who goes down to examine the reality directly. When you identify whether you’re working with an argument, a model, or an empirical observation, you stop guessing and start knowing.

But don’t become an atomicity zealot. The principle serves your thinking, not the other way around. Sometimes your future self needs comprehensive context on a single note rather than a “perfect” atomic note. Sometimes an idea deserves unleashing the kraken, and sometimes it is worth only a quick Level 2 pass. The tier system I provided helps you allocate your precious mental resources where they will have the greatest impact.

The four-step process, from free writing, heuristic evaluation, knowledge building block identification, to comprehensive development, gives you a systematic approach to refine your ideas. Yet the process remains flexible enough to accommodate the natural messiness of thinking. Your Zettelkasten should be a home for your mind in all its stages of idea maturity, from incomplete thoughts to fully developed ideas.

Remember the paradigm shift at the heart of the Zettelkasten Method: You’re not solving problems for your present self, you’re improving the life of your future self. This requires embracing the difficulty of getting to the essence of ideas rather than seeking shortcuts. The reward for the hard work is complete mastery of the ideas you choose to develop.

Atomicity connects directly to thinking skills because it trains you to work with the fundamental building blocks of knowledge. When you can reliably identify and work with concepts, arguments, and models, you develop the mastery of raw materials that underlie both critical thinking and systems thinking. This is why note-taking becomes a virtuosic skill—it’s not about the notes themselves but about training your capacity to think clearly and systematically.

As you implement these ideas, start with Step 1: free writing without hesitation. Let your thinking flow, then gradually apply the evaluation criteria. Don’t let the pursuit of perfect atomicity paralyze your note creation. The maturation process can unfold over months or even years for the ideas that deserve it.

The Zettelkasten Method, at its core, is about creating an integrated thinking environment that amplifies your cognitive abilities over time. Atomicity is one of the key principles that makes this amplification possible, but only when applied with wisdom rather than rigidity.

Take Action

- Subscribe to our newsletter to learn more about the upcoming Zettelkasten Gym—a structured environment for developing these thinking skills through deliberate practice. Just as physical fitness requires consistent training, knowledge work mastery develops through sustained, focused effort.

- Join our forum discussion to share your experiences with atomicity, ask questions about specific implementation challenges, and contribute your own insights.

Your future self is waiting for the intellectual capital you build today. Go!

Discuss the guide on the forums

-

Originally, I called this level “Thinking Tools”. For the purpose of this article, I changed the name of the level. ↩

-

In practice, I think that Morgan works with her Zettelkasten, respecting the other direction. She mentions at the beginning of the video that an atomic note contains a “whole thought or idea,” and the notes that she is presenting look like this. This shows Morgan’s skill as a thinker and her good intuition. While coaching her mother, she takes care to fill in the gaps in her mother’s notes. So, it seems to me that she considers this aspect in practice. This speaks to Morgan’s high level of intuitive understanding. ↩

-

This inventory is part of my project to develop a pattern language for knowledge. ↩

-

Thomas R Baechle, Roger W. Earle, and Dan Wathen (2000): Resistance training, in: Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, Human Kinetics; Benedikt Mitter, Lei Zhang, Pascal Bauer, Arnold Baca, and Harald Tschan (2022): Modelling the relationship between load and repetitions to failure in resistance training: A Bayesian analysis, European Journal of Sport Science 0, 2022, Vol. 0, S. 1-11. ↩

-

Jeff M Reynolds, Toryanno J Gordon, and Robert Andrew Robergs (2006): Prediction of One Repetition Maximum Strength From Multiple Repetition Maximum Testing and Anthropometry, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2006, Vol. 20, S. 584–592. Dale A LeSuer, James H. Mccormick, Jerry Lawrence Mayhew, Ron Wasserstein, and Michael Dipl-Phys Dr Arnold (1997): The Accuracy of Prediction Equations for Estimating 1-RM Performance in the Bench Press, Squat, and Deadlift, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 1997, Vol. 11, S. 211-213. Werner W. K. Hoeger, Sandra L. Barette, Douglas F. Hale, and David R. Hopkins (1987): Relationship Between Repetitions and Selected Percentages of One Repetition Maximum, The Journal of Strength \& Conditioning Research 1, 1987, Vol. 1. Tomoko Shimano, William J Kraemer, Barry A Spiering, Jeff S Volek, Disa L Hatfield, Ricardo Silvestre, Jakob L Vingren, Maren S Fragala, Carl M Maresh, Steven J Fleck, Robert U Newton, Luuk P B Spreuwenberg, and Keijo Häkkinen (2006): Relationship between the number of repetitions and selected percentages of one repetition maximum in free weight exercises in trained and untrained men, J Strength Cond Res 4, 2006, Vol. 20, S. 819-23. ↩

-

Dale A LeSuer, James H. Mccormick, Jerry Lawrence Mayhew, Ron Wasserstein, and Michael Dipl-Phys Dr Arnold (1997): The Accuracy of Prediction Equations for Estimating 1-RM Performance in the Bench Press, Squat, and Deadlift, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 1997, Vol. 11, S. 211-213. ↩

-

Charles Poliquin (1988): Five steps to increasing the effectiveness of your strength training program, Strength \& Conditioning Journal 3, 1988, Vol. 10, S. . ↩