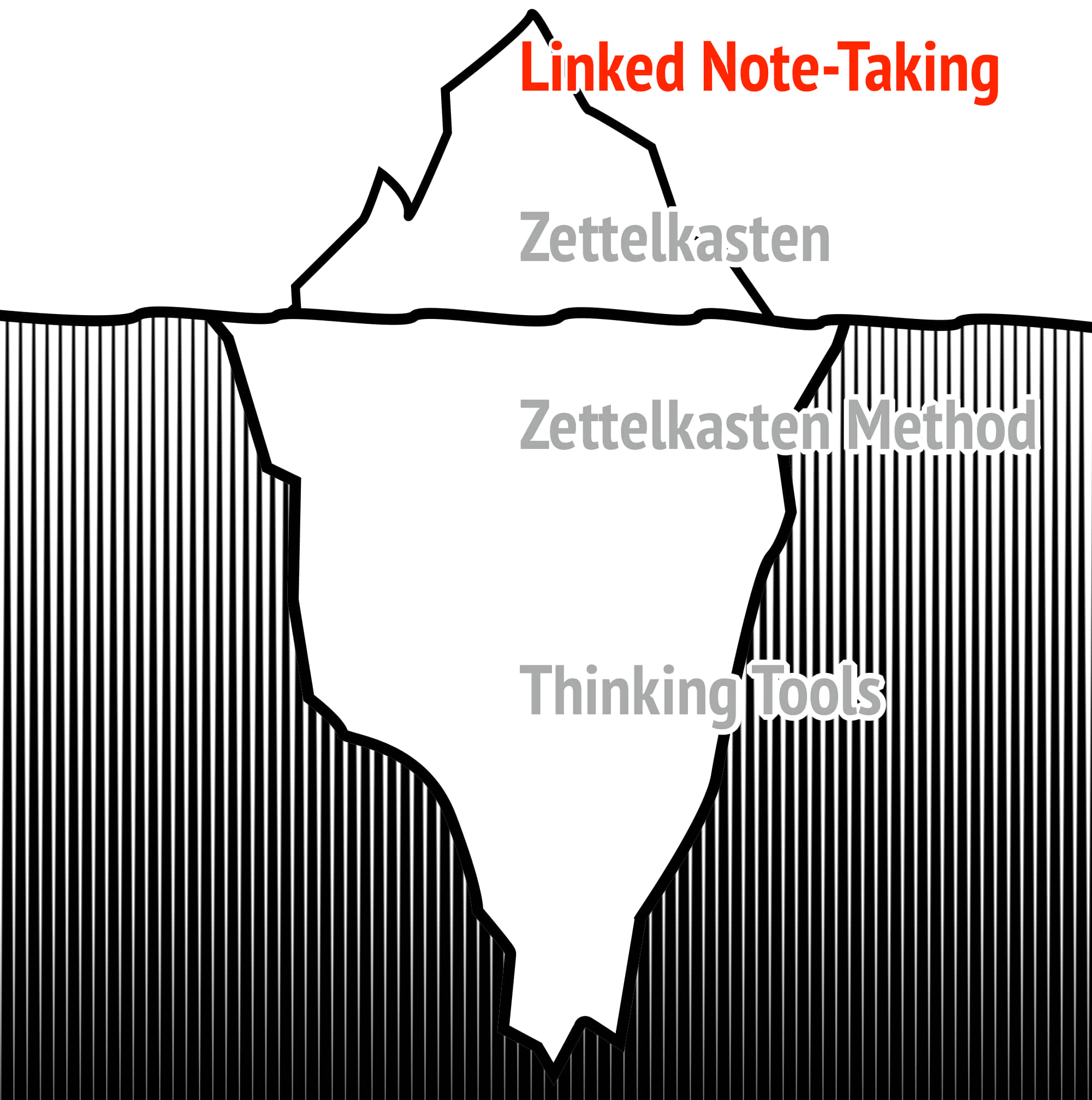

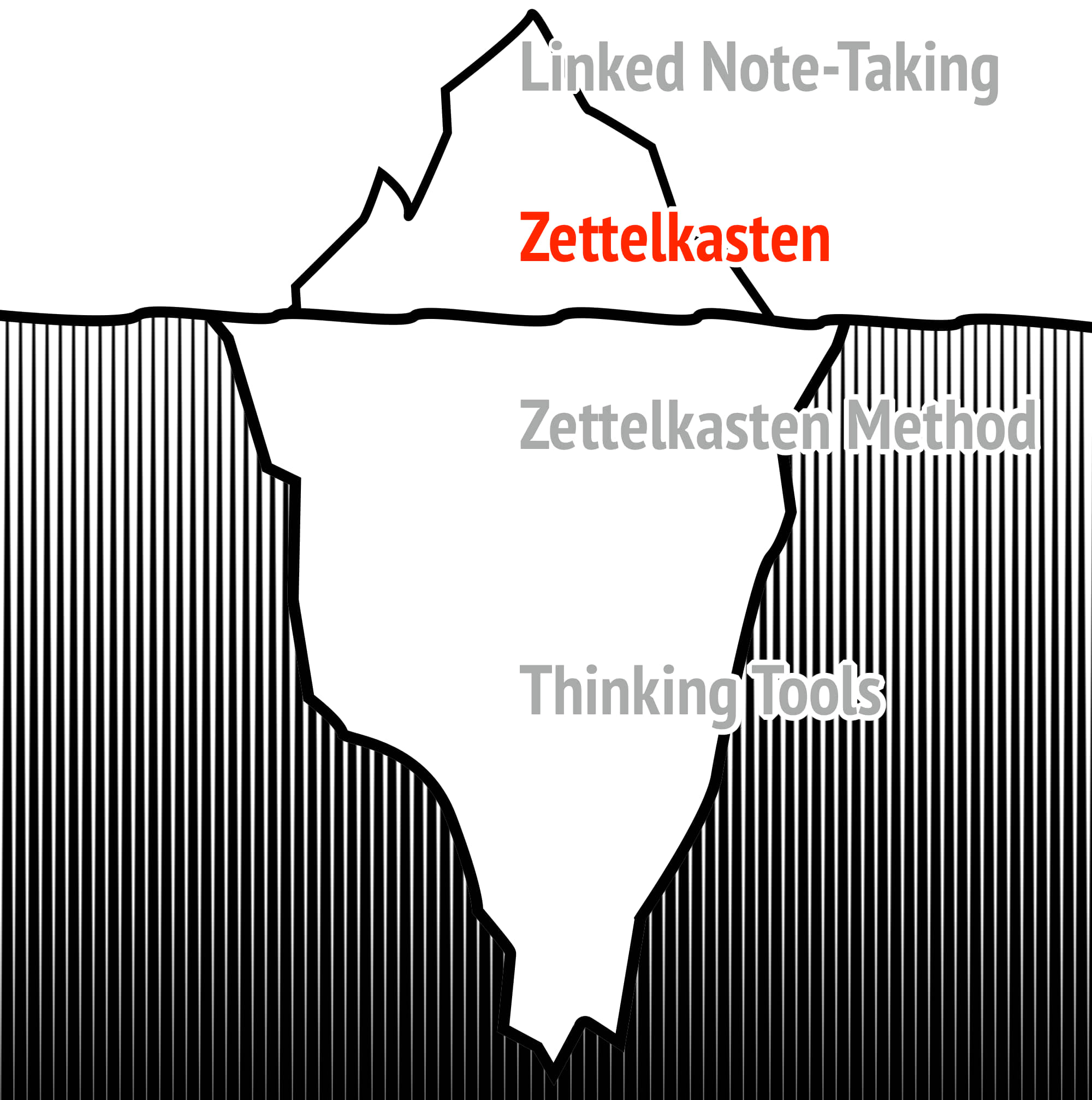

The Iceberg Theory of the Zettelkasten Method — Exploring the Depths

The Zettelkasten Method is not only a method of knowledge work. It is also a diagnostic tool.

To demonstrate this, I would like to start with a short story from my work as a health and fitness trainer:

A client contacted me because she wanted to lose weight. We discussed her situation and I sent her the first steps. One month later, she reported failure. She was unable to implement the program that we had discussed together. We reduced the program because my client said she was unable to implement it as planned due to time constraints and stress. The pattern repeated the next month. So we looked more closely for the causes. A surprising problem came to light:

She was complaining that her husband wasn’t supporting her enough. But in reality, she was skipping her workouts on her own to please her husband. Or to put it another way: she herself threw the agreements overboard. She has clearly demonstrated that her own training and her desire to lose weight are not important enough to be considered part of family life.

Her difficulties in losing weight were not due to a lack of discipline or time. It was because she didn’t take agreements she had made seriously. When we talked about it, she understood the problem and agreed with my assessment. But she stuck to her convictions. What I identified as inconstancy and a flawed problem-solving strategy, she described as flexibility and insisted that each situation was unique and that no general solution would be possible. Of course, in subsequent meetings, she had a “good reason” for every violation of the agreement between her and her husband, as well as between her and me. But all her reasons were in fact rationalisations, symptoms of a deeper problem.

The point relevant to the Zettelkasten iceberg is that there is more hidden beneath the surface than is usually suspected. The true causes of my client’s weight loss problems lay in her faulty beliefs about how to resolve conflicts in relationships and in life. In order to lose weight successfully, my client had to deal with the deep structure of her life.

If we only tinkered with superficial aspects like the training plan or organisational techniques such as weekly reviews, she would not only become more frustrated, but would also blame her partner and herself.

I also observe the same basic pattern when learning the Zettelkasten Method. Many people hope that they can solve problems that lie deeper by using the Zettelkasten Method.

Therefore, let’s enrich the Zettelkasten Method with these deep layers of knowledge work.

Linked Note-Taking and PKM

At the forefront are the mainstream influencers of the new wave of note-taking and PKM (“Personal Knowledge Management”). Linked Note-Taking addresses a fundamental problem that we need to solve if we want to build a coherent system for ourselves, rather than creating project-based buckets such as a folder. This is the paradigm shift that I see with the new wave of linked note-taking: It is all about connection. Here we find all kinds of workflows and considerations. Unfortunately, they usually remain so superficial that they are sometimes misleading. One phenomenon at this level is the Evernote effect.

The Evernote effect is a term that describes the result of using a system without considering the effects of scaling. The most prominent example is the realisation by intensive users of the Evernote app that entering notes (usually in the form of “captures”) creates clutter. This needs to be contained through maintenance. The more you enter, the more energy and time you have to invest in maintenance. Eventually, the maintenance effort is no longer justified by a corresponding return. Building a Second Brain (BASB) by Tiago Forte has recognised precisely this problem. One of the main conclusions of the book is that if the system is to relieve you cognitively, it must not be complex to operate.

This is exactly the right conclusion if we want to solve the problems of the surface layer. Therefore, each of the four steps in the workflow CODE is designed to avoid effort. This increases efficiency:

Capture includes everything you fill your inboxes with. The recommendation is to do this with as little effort as possible and with the support of apps such as Readwise.

Organise should also be done quickly. Although Forte offers a clever folder system (which I use myself for source management, by the way!), Forte repeatedly emphasises that the exact structure is only relevant in relation to your current projects. So you shouldn’t get too obsessed with organisation.

Distilling is a method of preparing the text to process it later by highlighting what seems important and useful to you. Here I let Forte himself have his say:

Don’t worry about analyzing, interpreting, or categorizing each point to decide whether to highlight it. That is way too taxing and will break the flow of your concentration. Instead, rely on your intuition to tell you when a passage is interesting, counterintuitive, or relevant to your favorite problems or current project.1 (my emphasis)

Express Forte recommends dividing projects into small, easily manageable steps.2 This is classic advice, namely to divide large goals into smaller milestones and to organise this division in such a way that each milestone becomes a manageable task so that you don’t hesitate to tackle it.

For superficial problems, such as finding articles again or filing articles relevant to a project in a folder, BASB is excellent. That’s why I use it myself as an information management system as a feeder system for my Zettelkasten.

It’s definitely a big step in the right direction.

However, let’s remember my client’s story: problems can have underlying causes. If we want to solve these problems, we have to look for these underlying causes. The Zettelkasten is located at a deep layer, but it is usually misunderstood.

Zettelkasten – Without Method, but with Flow

Out of all questions about the Zettelkasten Method, the question on the workflow is the least interesting. I spent the first few years building up my Zettelkasten without once asking myself about the workflow. Even later, I only created the workflow as a two-step cycle:

1. Step: Collect

2. Step: Process

With the success of Sönke Ahrens’ book “How To Take Smart Notes”, the workflow took the center of the collective attention. In my opinion, this phenomenon of understanding the Zettelkasten as a workflow is based on the attempt to apply surface solutions to the deep layer.

Let’s go back to my client to understand what problems happen when you try to solve deep layer problems with surface methods: My client is not a trivial system that responds to a certain input (plan) with a certain output (weight loss). She is a human being with a complex inner life. Without taking her inner life into account, the plan cannot work.

The Zettelkasten promises to become a personal thinking machine (I prefer the term “thinking environment”). Since we have one personal Zettelkasten, not many project-specific Zettelkastens, we have to deal with the problem of scaling in a completely different way. Some examples:

- Specificity: If we create a note and want it to become part of a life-long system system for us instead of just for a specific project, we need to create it in a way that makes it valuable independent of the project.

- Time: If we are creating a note now that should be useful to us in 5 or 10 years, we need to create it in a way that makes it useful regardless of our current situation. After all, we will be a different person in the future.

- Size: If our notes are to become part of a single system, we have to learn to deal with completely different dimensions. The Zettelkasten must be easy to use with tens of thousands of notes.

- Complexity: When we start to link notes with each other, we are confronted with a much greater complexity than with conventional note systems.

This requires a completely different approach than merely managing sources or creating a workflow.

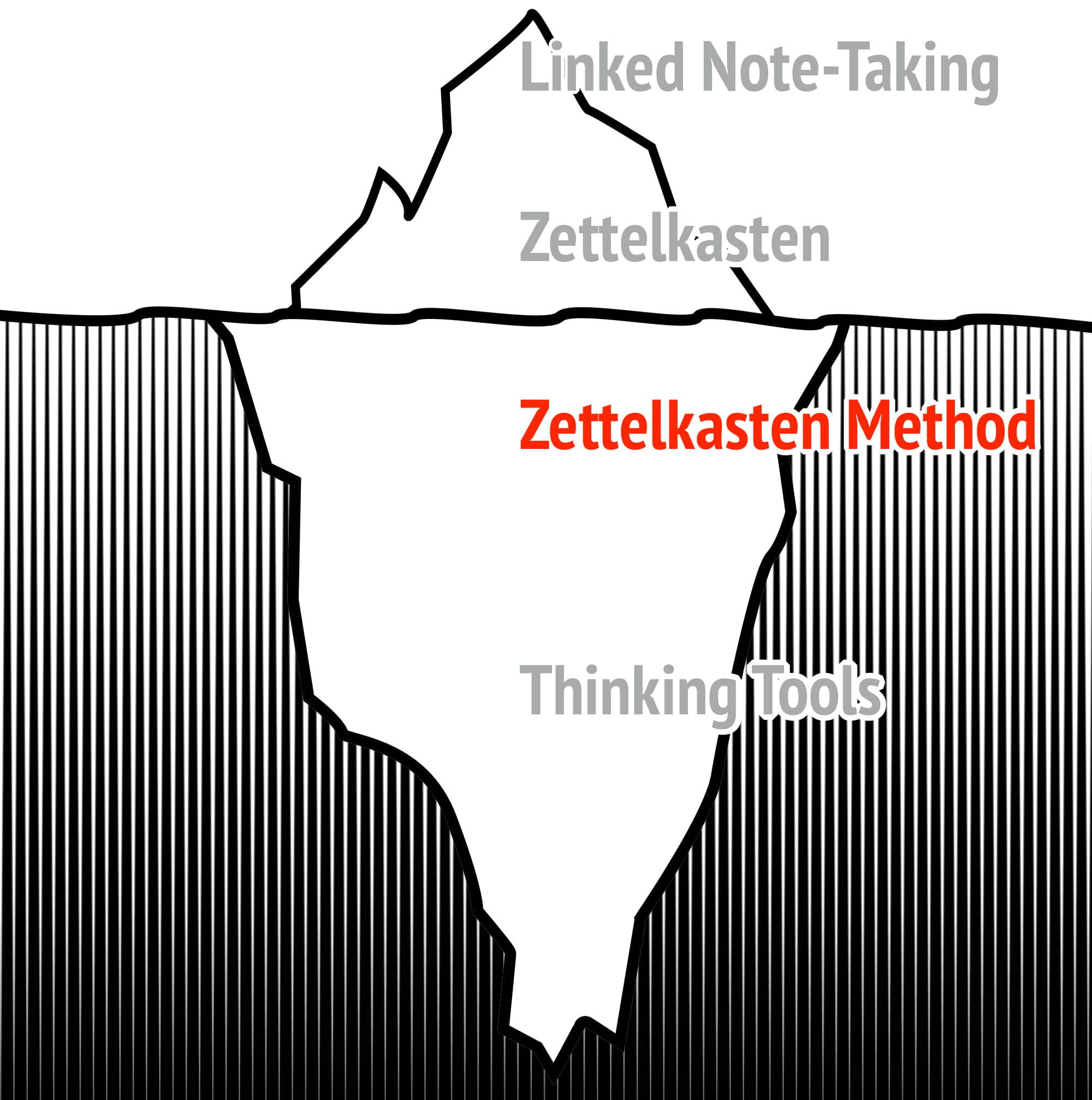

The Zettelkasten Method

In order to activate our Zettelkasten, we have to face a whole series of problems that we didn’t have before. This is where most people get stuck. Just as a new workout plan was not the solution to my client’s weight loss challenge, better management methods (“knowledge management”) or a different workflow are not the solution to building a lifelong system, a Zettelkasten.

Let me remind you of the Evernote Effect. There is the problem of scale. The way of working that benefits us in the short or medium term (e.g. for projects) is unsuitable in the long term. Notes that we write today should be understandable and useful in 5 to 10 years without their current context. The Zettelkasten must be easy to use with vast quantities of notes and, supported by methods and techniques, we must be able to find our way through an enormously high level of complexity.

At the same time, every interaction with the Zettelkasten must face a similar problem to that faced by website operators. Users are not willing to linger on websites that load slowly. I don’t believe that the cause is a decrease in our attention span, but rather a change in expectations. You could rather say that we now expect the internet to respond as smoothly as computer programs or even the world (yes, the real world has no loading times – depending on your sleep status and drug use, probably). When I use my Zettelkasten, I perform several searches in just a few seconds. I follow links in quick succession, sometimes more than one per second, only to return to the starting point. There is no room for laggy behaviour. Following the example of Notational Velocity, we have put much emphasis to the speed of The Archive. We don’t make negative comments about other apps, so I won’t mention any names: If I open my Zettelkasten with other, some very popular, apps, they become very unstable and laggy. The apps are just not prepared for a bigger Zettelkasten like mine.

Neither management methods nor a good workflow can solve the challenges at this level. For this very reason, I’m looking at the act of knowledge-based value creation itself (here and here) or how empirical work in Zettelkasten structures can be set up.

The basic course naturally provides concrete techniques and methods (e.g. how to assign titles or keywords and create structure sheets). But they aim to be solutions to problems of deep structure. These need to be solved if you want to have more than just a passive storage system.

If you want to build a Zettelkasten and unfold its magic[^2023-11-30-marvel-magic], you have to go into this depth and begin to understand the actual problems.

Let me give you an example of why the deep level is so important:

If we want to build a universal system and move away from project-based methods, we need to write the individual note in a way that benefits the system itself.

How do we write a note so that it has the greatest possible benefit for the Zettelkasten, so that our Zettelkasten becomes the best possible thinking environment for us?

My solution is to no longer relate the value of the individual thought to the project. When I write a note, I no longer ask myself first how it will advance a particular project, but ask myself how I can process the thought on it in such a way that I can enrich it with values independent of the project or whether it itself contains a value that can enrich other thoughts.

My model of the value-giving properties (truth, relevance, usefulness, beauty, simplicity) of knowledge serves as a template for knowledge-based value creation.

Such models have their origins in the deepest layer of the Zettelkasten Iceberg: the thinking tools.

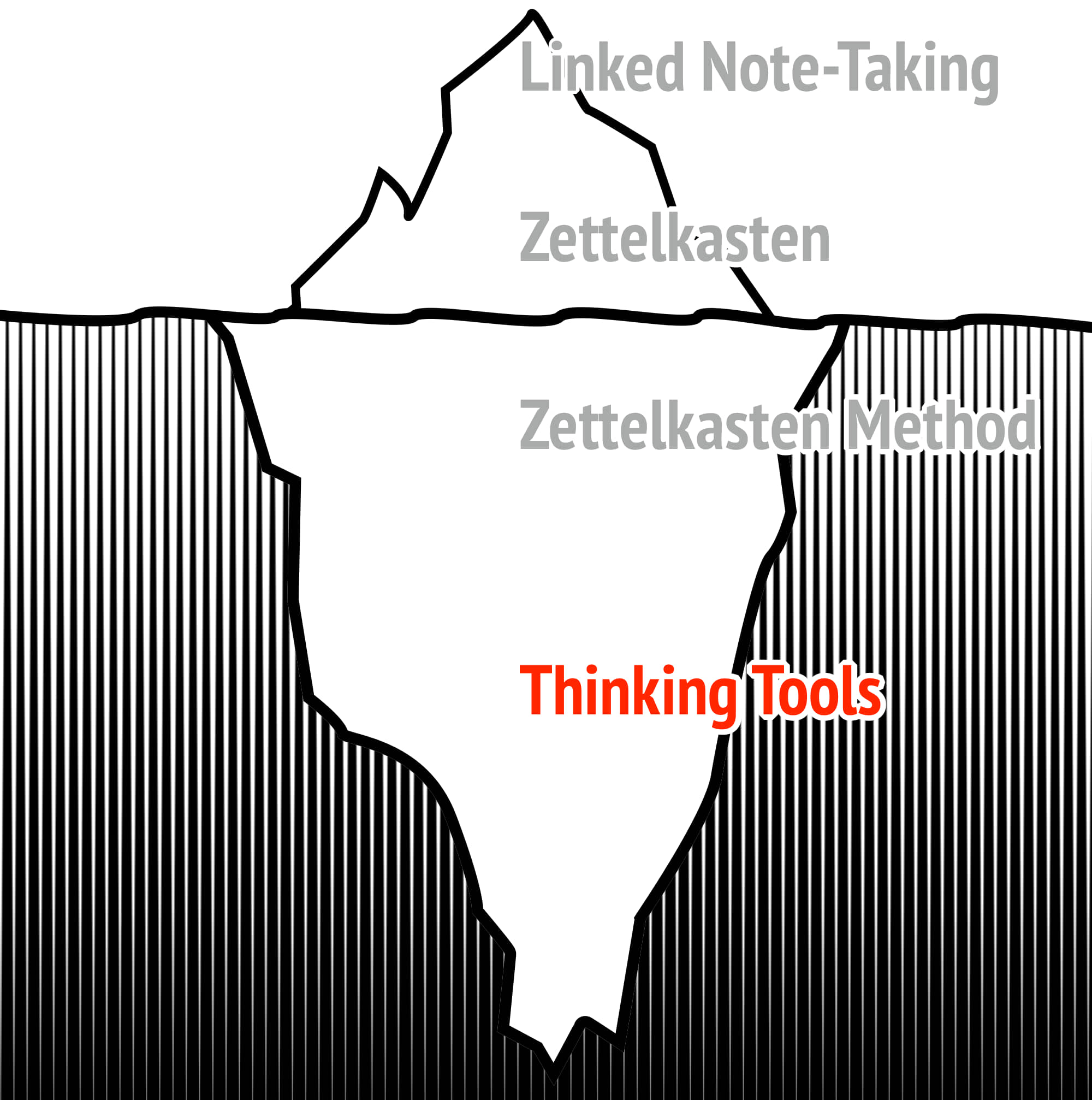

Thinking Tools

In the deepest layers live the Thinking Tools. The importance of this deep layer is not only largely ignored. It is also of particular importance for the quality of the notes you write and can write. This makes it one of the most common sources of error when setting up a Zettelkasten. However, the skills in question do not relate to the formalities of the Zettelkasten Method. They are the prerequisites for being able to grasp ideas clearly and perform knowledge work with confidence. It is therefore essential that you deal with this deep layer consciously. Not just to build a Zettelkasten, but because this is where the quality of your thinking is determined.

In short: Your thinking tools determine the quality of your notes and therefore also your Zettelkasten.

Thinking tools are tools for thinking itself. I would like to illustrate this with two of my notes from my Zettelkasten:

# 201705061036 The modelled object inherits the properties of the model

#Modelling #Theory #Inheritance #Property

When we model something, the modelled object not only inherits the desired property of the model. It inherits all properties.

This is both an opportunity and a risk:

1. it is an opportunity to gain knowledge, because when modelling we can become aware of inherited properties that we had not previously thought of.

2. it is a risk of attributing properties to the modelled object that do not exist in reality.

This article that you are reading uses the iceberg model. It is part of my inventory of thinking tools. The iceberg model has certain properties. One of them is the property of floating, which is caused by the buoyant force of the ice under the water. I took advantage of this to infer a relationship between the individual components of the PARA model (a knowledge management method) by Tiago Forte. The model helped me to arrive at this property, but at the same time I had to consider the risk that the model might suggest properties that do not occur in the modelled object (here: PARA).

This is one of the important steps you have to take in order to think cleanly: One must always check whether the properties inherited through modelling are demonstrable in the actual object of interest.

The above note is more or less part of my self-developed instruction manual for my thinking toolbox. Here, it is a warning, similar to the warning on a circular saw that it should never be left plugged in.

In the following note I have used a different thinking tool:

Disclaimer: The following note is translated from German. I roughly corrected the machine translation, but the intricacies and precision are lost. Please, don’t nitpick this note. (You are happily invited to nitpick on the rest of article!)

# 202311180746 Akrasia-Enkrateia - Self-control as part of Conditio Humana

#Akrasia #ConditioHumana #Self-control

**As people we are confronted with the constant negotiation between impulses and rational decision. We carry out this negotiation sometimes successfully and sometimes in vain. Because this negotiation is conditioned by our consciousness, the question of how we successfully organise this negotiation is part of the Conditio Humana.**

Akrasia and enkrateia refer to the relationship within our character of our will and our impulses:[[202311250926]]

A Akrasia is the state in which our will is subordinate to our impulses.

B Enkrateia is the state in which our will is superior to our impulses.

(1) Conditio Humana is based on the special situation of man as a result of his consciousness.[[202311240824]]

(2) The nature of consciousness leads to the fact that it is possible to have recognised what is right and yet act according to what is wrong.

(2.1) The rational (rationalistic?) assumption is that insight is a guarantee for action. It is disappointed.

(3) While animals follow their impulses without realising that what they are doing is wrong, we humans sometimes follow impulses in the knowledge that this leads to short-term pleasure with a long-term net loss for our lives.

(4) We observe in ourselves and other people that

(4.1) We make good decisions in some moments and bad decisions in others.

(4.2) That there are some people who make good decisions in principle and others who make bad decisions in principle.

(5) From this arises the question posed to us people *as people*, how we develop the quality of acting to the best of our knowledge and conscience, and avoid not acting to the best of our knowledge and conscience.

For analytic philosophers, numbering the statements is familiar territory: The above is an argument, at least the outline of an argument, for which I have not yet made a final formalisation. I could not say, for example, that it is a Modus ponens or Modus ponendo tollens. But this numbering gives me more cognitive control. When I look at the note, I immediately recognise from the form that it is an argument. I immediately know that I have to pay attention to formal correctness when using the note, or that I have to pay attention to my premises (basic assumptions) so that the argument is not only valid (logically correct), but also conclusive (I can also rely on the truth of the conclusion). Arguments are constructs to transfer the truth of some statements (the basic assumptions) to another (the conclusion). I must therefore ensure that the basic assumptions are true (by means of further arguments and empirical evidence) and that the transfer of truth is correct.

In my Zettelkasten, this is expressed by a certain reference structure. The argument establishes very specific connection points for other notes. Certain basic assumptions, for example, require detailed justifications. These must be put on another note or even several notes. The reason for this is not the blind adherence to atomicity. Rather, I am concerned with the ability to refer to individual components of the argument, with clarity, with reusability and many other properties that have been derived as partly necessary and partly useful by the Zettelkasten Method. It is therefore not the case that atomicity is a rule that you should follow blindly. Rather, atomicity is a principle that is followed for good reasons.

Most of the people who are interested in the Zettelkasten already have a whole range of thinking tools, but are not aware of them. For example, one of my clients is an engineer who is involved in Christian life counselling and is training for it. His model of God’s will was a cognitive feast in my eyes: clear, simple and with excellent explanatory power. All that was missing was a little knowledge from the Zettelkasten Method to organise the note in such a way that it was clear where links would be appropriate.

Most people have thinking tools that they have developed within their domain. These just need to be transferred to the Zettelkasten and harmonised with the Zettelkasten Method.

This is one of the challenging projects for me within the framework of the Zettelkasten Method: I am working on developing a general toolbox for thinking and training to use it. The first step will be a course on the unfolding of a thought.

Don’t Go Back to Basics, We Need to Go Deeper

Why is it not enough to simply copy Luhmann’s method? There are a few reasons for this:

- Few people are Luhmann. Luhmann was a workaholic, obsessed with his goal of creating a super theory of society. He was also a person who had administration in his blood (back then, this meant lots and lots of paperwork). Luhmann also had an enormous wealth of knowledge and an extensive toolbox of ideas at his disposal, which he was able to utilise thanks to a great deal of practice and experience.

- Those who merely copy Luhmann miss out on innovations and the opportunity to continue thinking about what Luhmann started. Remember: Luhmann was the first to create such a systematic Zettelkasten3 He is the pioneer, and it is our task to further develop what he invented.

- The environment is different. Luhmann had to solve a whole series of problems that we don’t have today. For example, finding enough references for publications was quite a challenge back then. Today, the internet makes them available with just a few clicks. Then again, he didn’t have to deal with digital dementia.

Moreover, some problems are not surface problems. If we want to create a Zettelkasten that has at least the characteristics that Luhmann’s Zettelkasten had, for example a kind of life of its own, we have to penetrate into its depths. Luhmann himself solved the first layers of depth by means of his system-theoretical approach.

Some may think that this is a bit much to ask. But there is no other way. You need this deep understanding so that you can use your Zettelkasten in the spirit of this understanding and not have to rely on misunderstood formulae such as “atomicity”. Otherwise, you are dependent on bluntly copying what others say. This is the case in every area of life. For example, if you don’t have a basic understanding of how the body works, you can’t independently adapt your training and diet to the situation or yourself. This is not so important for someone who just wants to be healthy and fit compared to the average modern person. But you can’t fulfil higher demands with it. I’m not a competitive athlete, so I don’t need that, you might argue. I recommend that you read Peter Attias Outlive. The prerequisite for leading a healthy life in old age is a performance at a young age that would be categorised as “excellent” (top 5%). More concrete: if you want to go on a long hike in your 70s that you can enjoy and not just endure, you need to have an enormous amount of stamina in your 30s. (Of course, there is hope: you can start training at any time and improve enormously).

After all, the purpose of the Zettelkasten is not to write a short term paper or a superficial presentation for school. The Zettelkasten should serve as a thinking tool for tasks that push you to the limits of your mental capacity. For some, it means that they have to assert themselves against competitors in the world of finance. For others, it means gaining new scientific knowledge and being able to publish it. Whether it’s improving business models, a deep understanding of football training methods, an overview of programming architecture theory or something similar. If you are reading this, you are an intellectual high performer. Treat yourself accordingly.

Practical implications

- Work your way down from the top of the iceberg to all the depths The realisation that linked notes are more useful than unlinked notes should be the start of your journey into the depths.

- If you’re having trouble getting your system to work, use the iceberg as a diagnostic tool. In my experience, many problems stem from the deep level. To put it simply, how are you going to pin down an argument if you don’t know what exactly an argument is? You’d be like a dog catcher who can’t tell the difference between a cat and a dog.

- Practise formalisation If you capture an argument, formalise it to make it easier to understand. If you are capture a model, actively think through what the aspects of reality it maps are and how exactly the model relates these aspects to each other.

- Use the skills and tools you already have If you’re an engineer, you’re already an expert at representing problems, using models, and inferring causal chains. Let these skills shine in your notes.

Christian’s comment: This is such a tough decision: where do you want to go deep, and when do you want to go down there? Sometimes working with the Zettelkasten is a time sink, because going into depth is always possible, so it’s easy to fall into all kinds of rabbit holes. Not every idea and every topic warrants full dedication. I’m thinking of code snippets, i.e. self-contained solutions for a programming task, designed to be reused later. These are similar to instructions in a cooking recipe, so take, for example, “how long do I need to cook potatoes to make them digestible?”. Am I being lazy when I stop at capturing a solution like “15–25 minutes, depending on size; poke inside to test softness”? I could go deeper and discuss the actual problem, as in why the solution works, say “why does heating the potato make it digestible at all?” Then generalizing, why does heating make so many things more digestible? – Sometimes, there is value in going that deep. (Talking about life-long value, it certainly doesn’t hurt to understand cooking and digestion a bit more!) Sometimes, going deeper can be a waste of time. With code snippets, that is the case when I’m not interested in the programming environment in the future but believe I will need to perform this one task again.

-

Tiago Forte (2022): Building a Second Brain, Great Britain: Profile Books, p 140. ↩

-

Tiago Forte (2022): Building a Second Brain, Great Britain: Profile Books, pp 151. ↩

-

The other Zettelkastens were not created as a coherent system, but as loose collections. This is precisely what Luhmann decided against, which is why it is a methodological error to understand Luhmann’s Zettelkasten as one among many. It undoubtedly has a special property. ↩