The Principle of Atomicity – On the Difference Between a Principle and Its Implementation

There was a bit of backlash on Reddit regarding the video on using the Zettelkasten Method for Hindu Philosophy.

The core point of criticism was about the lack of atomicity of the notes. Isn’t the Zettelkasten all about having atomic notes?

I like to take the opportunity to explore the principle of atomicity, as I believe the misconception of atomicity as a principle is hindering the progress of many people.

A Principle is the Intended Pattern Underlying an Implementation

It is not the first time that this topic has come up. The great Folgezettel Debate was started by me reacting to Daniel Lüdecke, creator of ZKM³. He claimed that Folgezettel is essential to a Luhmannian Zettelkasten. My counter-position was and still is that the whole reason to use a particular numbering scheme was to enable direct linking, since Luhmann self-stated:

With this technique, it is not1 important where you place a new note. When there are multiple options, you can solve the problem by placing the note wherever you want and creating references to capture other possible contexts. (My Translation)

The principle of the Zettelkasten Method, established by Luhmann, enables and establishes connections between individual notes.

In the context of the Zettelkasten Method, a principle is a general guideline on how to set up a Zettelkasten and work with it. Enabling and establishing a connection is the underlying principle of the Folgezettel technique.

You could also make the case for the principle establishing an objective, and the technique being the tactic for fulfilling this objective.

The basic rule is that principles are what is constant; techniques vary from instance to instance. As long as you enable connections and establish them, you adhere to the underlying principle, whether you use the Folgezettel Technique or a timestamp-based ID.

Now that we have that settled, let’s move on to applying the difference between a principle and its implementation to the principle of atomicity.

Atomicity as Principle vs Atomicity Implementations

The principle of atomicity in note-taking is from 2013, coined by Christian:

The underlying principle I’d call the principle of atomicity: put things which belong together in a Zettel, but try to separate concerns from one another. For example, I might collect a list of assumptions in one Zettel which serves as an overview. like hard determinism. A related argument and its conclusion will be kept in another Zettel. Moral responsibility under hard determinism is a good example. I can re-use the arguments without buying into the assumptions because the arguments are of sufficiently general form. Atomicity fosters re-use which in turn multiplies the amount of connections in the network of Zettels.

In a footnote, he explains the term “separate concerns”:

If you’re a programmer, separation of concerns should ring a familiar bell. I deal with notes in a fashion similar to complex code. Instead of writing classes, I create new note files. Accordingly, patterns emerge: there are argumentative notes; there are notes with term definitions; there are sparks and ideas. Each Zettel pattern fulfills a different purpose.

We can see that the idea of atomicity was still in its infancy, undeveloped and more of an applied association than a fully formed idea. But its viral spread showed that it resonated with people.

The single concern was substituted for “single idea,” and voilà!, the concept of the atomic note was born.

When Do We Achieve Atomicity? Two implementations!

The two major implementations are these two:

- Atomicity as the input type. Notes that end up in your Zettelkasten should be atomic or shouldn’t be in your Zettelkasten after all.

- Atomicity as the desired outcome. You constantly aim for atomicity.

The first implementation, atomicity as the input, imposes the major problem I will dive into.

First, I have to call myself out. Even in my own introduction, I give the impression that everything in the Zettelkasten has to be atomic right away:2

(…)a Zettelkasten needs to adhere to the Principle of Atomicity. That means that each Zettel only contains one unit of knowledge and one only.

Atomic notes are presented as something that you put in your Zettelkasten. That means that your notes should be atomic before you put them in. In practice, this is not the case. Just take the constant opportunity to break up notes.

- Sometimes, you find that you made a mistake. A note that you thought was atomic contains more than just one idea. Then you break up the note into atomic notes. Atomicity was achieved in your Zettelkasten, not outside of it.

- Sometimes, you work on an existing note and find that to put your thinking properly, you have to break up the note. You didn’t make a mistake, but working with the note and changing it over time led to its loss of atomicity, which you reestablished in a second step. Again, atomicity was achieved in your Zettelkasten, not outside of it.

These are typical use cases that show that atomicity is established within the Zettelkasten in practice anyway.

This is highly important because it changes our perspectives on the above instances from being a mistake or even disqualifying our system as a Zettelkasten to steps in the process of achieving atomicity.

If this happens anyway, why not incorporate this into our workflow to not only tame this process, but also benefit from this?

A significant benefit of this change of perspective is that it gives us a lot more freedom to. Notes become more malleable. No longer do we have to be anxious about atomicity, since it is no longer a hurdle to overcome. Instead, atomicity is part of the journey guiding our thinking.

Sometimes, you have an excellent grasp of the idea that you are processing. You create the note with a high confidence in its atomicity. Other times, you are not sure about the concept: Is it just one idea, or is it a whole bundle of ideas?

The atomicity of a note is doubted quite a lot. The Zettelkasten Method has to consider this uncertainty.

Therefore, the particular implementation of only allowing ideas into your Zettelkasten if they are captured in an atomic note creates quite a few problems.

- It creates anxiety about being right about atomicity right away. This is not irrational, since the assumption behind the implementation of atomicity as a type of input is that all notes need to be atomic to create a functioning Zettelkasten.

- It ignores the reality that notes are often not atomic, but the Zettelkasten works fine. The principle of atomicity aims to establish particular characteristics of the combined system of the user and their Zettelkasten. Some of these characteristics (note reusability, linking to facilitate association and creativity, etc.) are still in place.

- It moves a significant proportion of the thinking outside of the Zettelkasten. If the input has to be atomic, you have to figure out the atomicity outside of the Zettelkasten. However, this is a significant proportion of the whole thinking process. Figuring out the components of the idea and getting to its essence is what we call “understanding”.

- It nudges us to underdeveloped notes. This might be the most damaging aspect of this implementation. To deal with the uncertainty behind atomicity, many default to capturing claims. If you review the note examples of presentations of the Zettelkasten Method, you’d find that most notes contain merely one statement.

Please take a look at Bob Doto’s demonstration on how he writes with his Zettelkasten. He doesn’t use his Zettelkasten to think or to figure anything out. Almost all of his notes are merely statements that offer little beyond the title, and the major work is done outside of his Zettelkasten in a separate file.

His Zettelkasten is a prompt machine. This works if you write about stuff that you have reasonable knowledge about. It doesn’t work if you are challenged and push yourself to the limits of your cognitive capacity. Here lies the reason why the Zettelkasten Method is mistaken as a tool for writers. If you are a writer who already knows how to write, this clearly applies to Bob, then curated prompts are just enough to get your writing flow going. If you are trying to build knowledge, this approach doesn’t work.

For this writing process, you don’t need a Zettelkasten at all. Just use a flat outline as Cal Newport. The similarity is striking: You dump material into a file and then work out the text there. Notice that the text will inherit the characteristics of the raw material. Newport will put a mix of anecdotes, news articles, and scientific papers in the file and can produce his long-form articles for the New York Times or his books. In his demonstration, Bob puts claims about spiritual practices in his file and is at the beginning of producing a typical opinion piece about spiritual practices.

Let me throw a third “Zettelkasten” user into the mix: Ryan Holiday. He collects quotes from his reading and puts them into various categories, which then can be used as writing prompts. (Read about his Zettelkasten here)

There is a single paragraph that stands out to me that highlights the difference between the consequences of this kind of implementation of the principle of atomicity, as described by Mr. Holiday, and mine.

What if something happened to your box? My house recently got robbed and I was so fucking terrified that someone took it, you have no idea. Thankfully they didn’t. I am actually thinking of using TaskRabbit to have someone create a digital backup. In the meantime, these boxes are what I’m running back into a fire for to pull out (in fact, I sometimes keep them in a fireproof safe).

Contrast this with what I wrote last November:

If you would destroy my Zettelkasten, the work building it would still be worth it. (Source)

While both quotes are compatible and I, too, would go to great lengths to save my Zettelkasten, the differences in the underlying sentiment are vast. The reason is that Ryan Holiday is building a prompt machine that simultaneously allows him to write referenced books. Being diligent with the input, he will create a curated prompt machine to assist him during the writing process.

I won’t go into full detail with Luhmann’s Zettelkasten. But if you take a look at his notes, you will find a striking similarity to the style of Cal Newport’s quote dumps, Bob Doto’s notes on spiritual practices, and Ryan Holiday’s quote collection. Luhmann, too, built a prompt machine to help him write. The complexity of his system was appropriate to the complexity of his work. But take this statement by Johannes Schmidt:

Luhmann described the process of drawing on his file to compose texts as a kind of collaging technique in which he combined the various sections on issues that are relevant to a topic.

Sounds familiar? If yes, you got it!

Atomicity as the input quality of notes creates a prompt machine.

That doesn’t exclude that the Zettelkasten can prompt you to write more notes within the Zettelkasten. But as long as you stick to this relatively narrow and inflexible implementation of atomicity as a principle, you tend to get interconnected prompts. Claims and opinions to which you sometimes attach a reference if you took it from another person.

The different approach, atomicity as desired outcome, is far more flexible and therefore can adapt to many different use cases and user cases.

First user case: If you are already a capable writer like Bob Doto, Cal Newport, or Ryan Holiday, you can create these idea prompts to help you write. Your Zettelkasten will be an interconnected web of opinions that you can draw upon. However, unless you are engaging with such a highly complex and vast topic like the social systems theory, you are much better off with a simple system. I’d opt for Ryan Holiday’s approach.

Second user case: If you are like me, pushing your mind to the limits of your cognitive capacity, you can treat atomicity as the desired outcome that might be at the end of a long process that happens within the Zettelkasten. Studying Hindu philosophy is such a use case, too. For the sake of atomicity, I actively recommended postponing the atomisation to a level of understanding that allows you to isolate ideas with reasonable confidence. That means that notes are not atomic for a long time, but continuously approach atomicity as a desired outcome. This allows you to start the thinking process almost immediately in your Zettelkasten. Practically speaking, you start writing in your Zettelkasten right away and figure out the atomicity of your notes during this process. But the timeline is up to you and the material.

These are two user cases that are both covered by atomicity as the desired outcome. The first user case is that you can create fairly atomic notes right away. The second user case is that you have to work hard for atomicity because of the inherent challenge to your mind. The beauty of this implementation is that it is possible to follow both different approaches within the same Zettelkasten. From the perspective of atomicity as the input, the Zettelkasten would have domains in which notes are atomic and therefore proper, and other domains that are not atomic and thus improper. From the perspective of atomicity as the desired outcome, the domains are just on different stages in the process.

This is true for my Zettelkasten. In some areas, my notes contain concise statements, which is particularly true for my collection of mythologems.

Title: Mythologem - Two different teachers

Gestalt: The protagonist has two teachers who are very different.

Meaning: There is no single way of being in this world. There are distinct ways of being, while the highest form of being is to master all the ways so that you can remain still amidst change.3

Other areas, like training methodology or habit work, contain quite long notes that are not strictly atomic yet. Their atomicity will be established on the demands of the material.

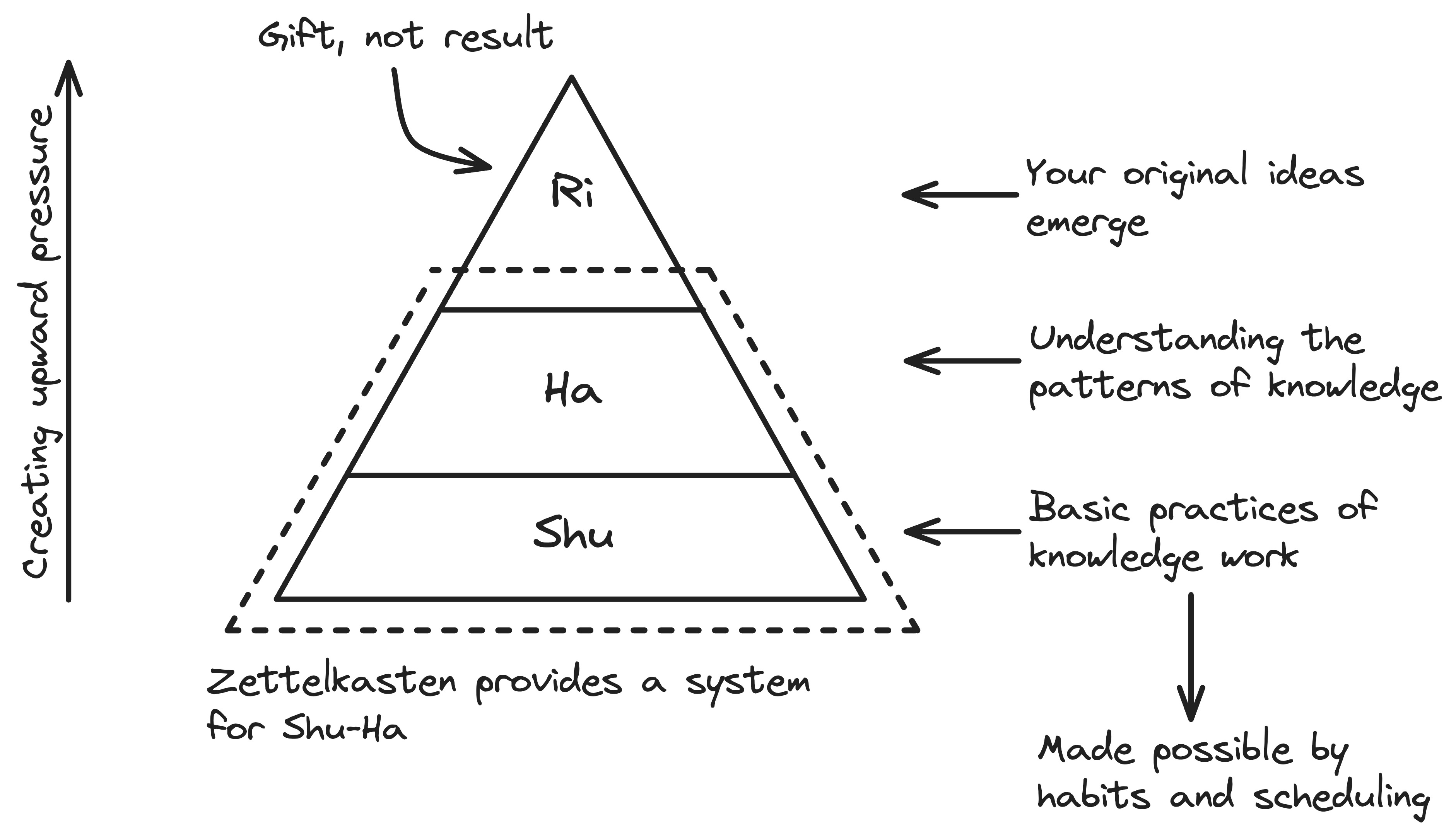

This shows the difference between a principle and its implementation. Your ability to distinguish between the principle and its implementation, but also your ability to apply a principle, depends on your level of mastery.

This is a mastery model that I initially encountered in the domain of martial arts. It is both descriptive and prescriptive. It describes various stages of abilities:

- In SHU, you can imitate, but neither understand nor create.

- In HA, you can understand and act on a higher-level guideline to produce situation-appropriate deviations from what you learned, but you cannot create.4

- In RI, you unlocked the ability to create, but you can always perform as if you are on a lower level.

There is absolutely no shame if you are in SHU, reading this as an aspiring Zettelkasten user, or just as someone who wants to learn more about the skills of working with knowledge and having tried to imitate what you saw. In fact, this is the right action at this stage. I, myself, did start purely imitating to the best of my ability what Luhmann described in his infamous article. This is how you begin.

With this mastery model equipped, you might already anticipate the content of this paragraph: My goal in teaching the method is to push people at least to HA. On HA, you can adapt the principle to the needs of your specific situation. Speaking in terms of atomicity, you will be able to decide when and how you aim for atomicity. You will be able to determine whether the input should be atomic or doesn’t need to be. Ultimately, it simplifies a lot of the way you work with your ideas, since the principle as a guideline is much more potent than any recipe.

Principles are higher than techniques. Principles produce techniques in an instant.

—Ido Portal

So, now we have learned about two implementation styles of the principle of atomicity. Let’s explore the principle of atomicity more deeply to get a fuller picture.

Everybody Talks About Atomicity, Nobody Ain’t Talking About the Atoms

What is this thing called “idea”? If you want to capture one, how do you make sure that you just put an idea on the note and not an entire idea? This is what you never seem to hear about.

As someone who publishes on this topic, you can easily avoid the problem by just presenting notes that contain a single claim. Luhmann himself had such notes:

(9/8b2) “Multiple storage” als Notwendigkeit der Speicherung von komplexen (komplex auszuwertenden) Informationen.

EN: “Multiple storage” as the necessity of storing complex (to be evaluated in a complex way) information.

This is not even a fully formed claim, which would be “To store complex information, you have to use multiple storage.”

I challenge you to review any source for so-called atomic notes for a good definition of what a knowledge atom is. I bet you won’t find any, my introduction included.

Currently, “atomic notes” is a beetle-in-a-box-phenomenon. The beetle-in-a-box is a thought experiment by the late Wittgenstein:

DE: Angenommen, es hätte Jeder eine Schachtel, darin wäre etwas, was wir »Käfer« nennen. Niemand kann je in die Schachtel des Andern schaun; und Jeder sagt, er wisse nur vom Anblick seines Käfers, was ein Käfer ist. – Da könnte es ja sein, daß Jeder ein anderes Ding in seiner Schachtel hätte. Ja, man könnte sich vorstellen, daß sich ein solches Ding fortwährend veränderte. – Aber wenn nun das Wort »Käfer« dieser Leute doch einen Gebrauch hätte? – So wäre er nicht der der Bezeichnung eines Dings. Das Ding in der Schachtel gehört überhaupt nicht zum Sprachspiel; auch nicht einmal als ein Etwas: denn die Schachtel könnte auch leer sein. – Nein, durch dieses Ding in der Schachtel kann ›gekürzt werden‹; es hebt sich weg, was immer es ist. - Page 165, Source

EN: Suppose everyone had a box containing something we call a “beetle.” No one can ever look into another’s box, and each person says they only know what a beetle is by looking at their own. – It could well be that each person has a different thing in their box. Indeed, one could imagine that such a thing constantly changes. – But what if the word “beetle” still had a use among these people? – Then it would not be used to designate a thing. The thing in the box is not part of the language game at all; not even as something: for the box might even be empty. – No, this thing in the box can be “canceled out”; it disappears, whatever it is.

You will find a lot of descriptions for the box: “Short notes”, “concise notes”, “single idea”, “single thought”, and similar phrases. You will find statements like “It is up to you” and “Everything is relative.” You will find everything and anything that avoids opening the beetle box. The one premise of the beetle-in-the-box thought experiment is not valid in real life: We can open the box by learning about the atoms that we are supposed to capture.

The damage done by this language game is that quite many people rip their thoughts into notes, mimicking the “atomicity” presented online. Nori vividly explains how this feels.

The publication of this article will be the threshold date. If you find any article that explores what an atom is (not heuristics!) that precedes this article, you win yourself a free coaching session with me.

I am serious about that because it is both a fallacy and a malicious trick to use beetle boxes. Often, it is necessary, since we can’t open every beetle box we use. But often, beetle boxes are a tool to sell something without having done the work required to master this. In self-help, psychology, spirituality, and many more fields, people use beetle boxes because it is a means to play a language game. Or think of the typical politician’s speech patterns. As long as we allow ourselves to be trapped in the language game, contact with reality is optional. Perfect, if you want to avoid a reality check.

What is this atom, then?

I use an inventory of six types of atoms, called knowledge building blocks, which I developed in 2011. This inventory has remained stable ever since, and I have never encountered any issue (e.g., inconsistency, inapplicability) for more than a decade. So, I am confident in this inventory.

What are the benefits of engaging with knowledge with this inventory in mind?

- Mastering this inventory gives you a precise method of identifying individual atoms, knowledge building blocks. Atomicity is no longer guesswork.

- More generally, you will be able to identify the essence of an idea with a working framework, instead of guesstimating.

- Each building block relates to the other building blocks functionally. If you master these functions, you will know how each building block will fit together.

My favourite example is the argument.

An argument has exactly three different elements:

- The premises are the statements which truth you want to inject into the conclusion.

- The logical form, which, if it is valid, is a structure that receives true premises and makes conclusions true.

- The conclusion, the statement that receives the truth from the premises through the logical form.

A note that captures all three elements of the argument and nothing else is atomic in a strict sense. So, from now on, you never have to have any doubts about the atomicity of a note if it contains an argument. Make sure that you put these three elements and these elements only into your note if you want to make an atomic note about an argument.

These knowledge building blocks are the result of a major principle of the Zettelkasten Method of my flavour:5

The Zettelkasten Method works best within the constraints of the objective nature of knowledge.

My claim is that the knowledge building blocks are not arbitrarily cherry-picked constructions. Instead, knowledge is formed by discrete building blocks, of which there are six types. Obviously, I can be wrong about the content of the inventory. There may be a seventh item, or one item isn’t an actual building block. But that there is an inventory of knowledge building blocks is my claim.

This is how I solved the problem of atomicity. The basic argument is as follows:

- Premise A Knowledge is organised in discrete building blocks called knowledge building blocks.

- Premise B The atoms of atomic notes are knowledge-building blocks.

- Conclusion Therefore, an atomic note is a note that contains exactly one knowledge building block.

This fits nicely with my reasoning of atomicity as a desired outcome. You don’t need to know which building block you want to capture on a note before you create the note in your Zettelkasten. Identifying the knowledge building block is part of a process that can happen either before you make the note or after the note creation. Identifying the knowledge building block is a formalisation technique of creating atomic notes.

This idea was likely inspired by my coming into contact with analytical philosophy. These texts are interlaced with formalised arguments.

Ansgar Beckermann, one of the best contemporary philosophers, says:

After the lecture, Carnap had to address an objection raised by Arthur Lovejoy, and he did so in a manner characteristic both of himself and Analytic Philosophy: “If Arthur Lovejoy means A, then p; if, however, he means B, then q.” This delightful anecdote is highly revealing. It clearly illustrates one hallmark of Analytic Philosophy: the attempt to work out the content of a thesis as precisely as possible, even at the cost of being tedious or even boring. (My translation.)

The result of this formal approach is indeed tedious or even boring. Reading analytical philosophy is similar to reading mathematical papers. If you like it, you are a very rare person. Not even mathematicians like it too much.

In practice, I formalise only a small fraction of the notes. Since I have mastered these thinking tools to a sufficient level, I trust my future self to do whatever the note needs.

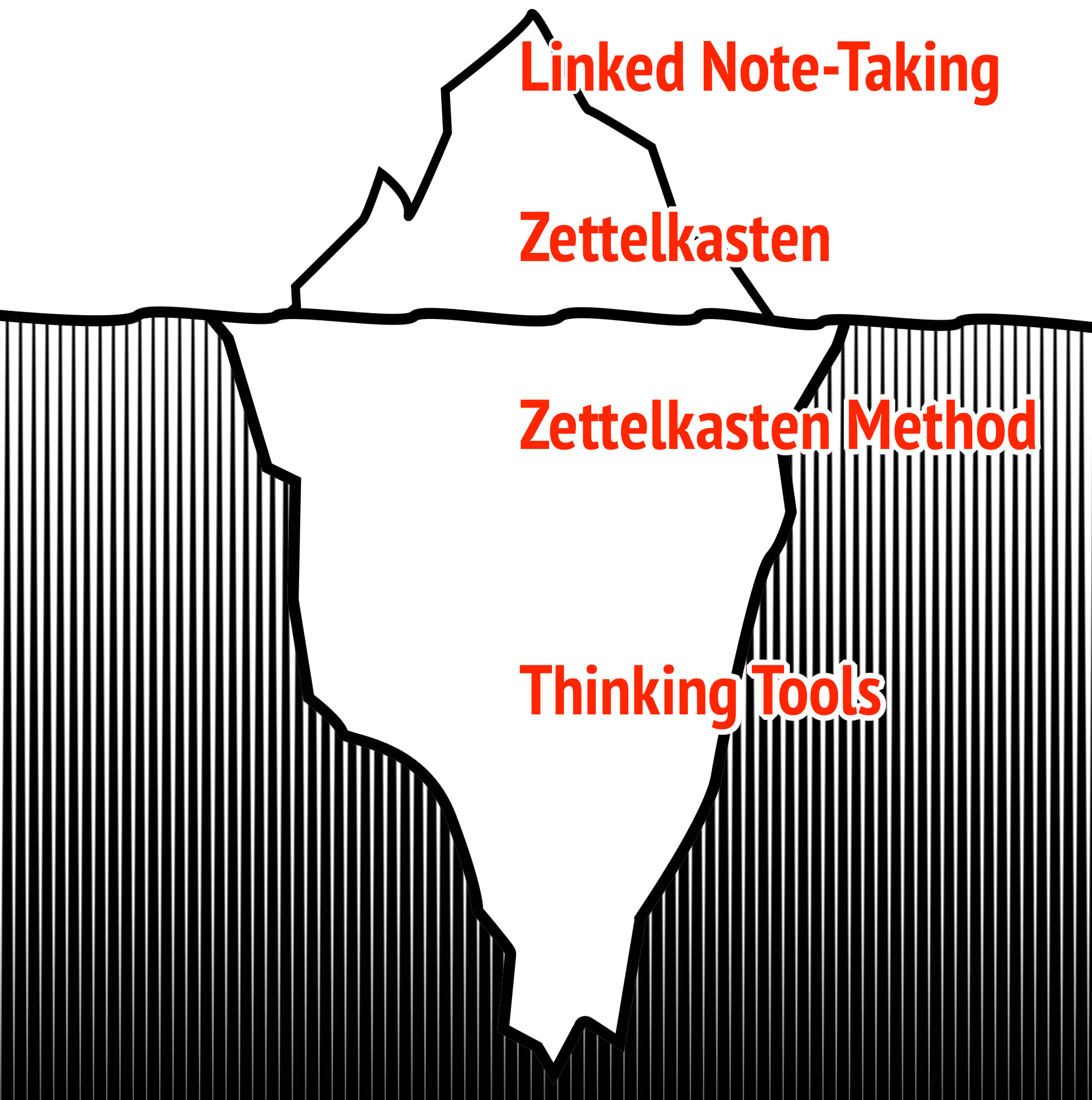

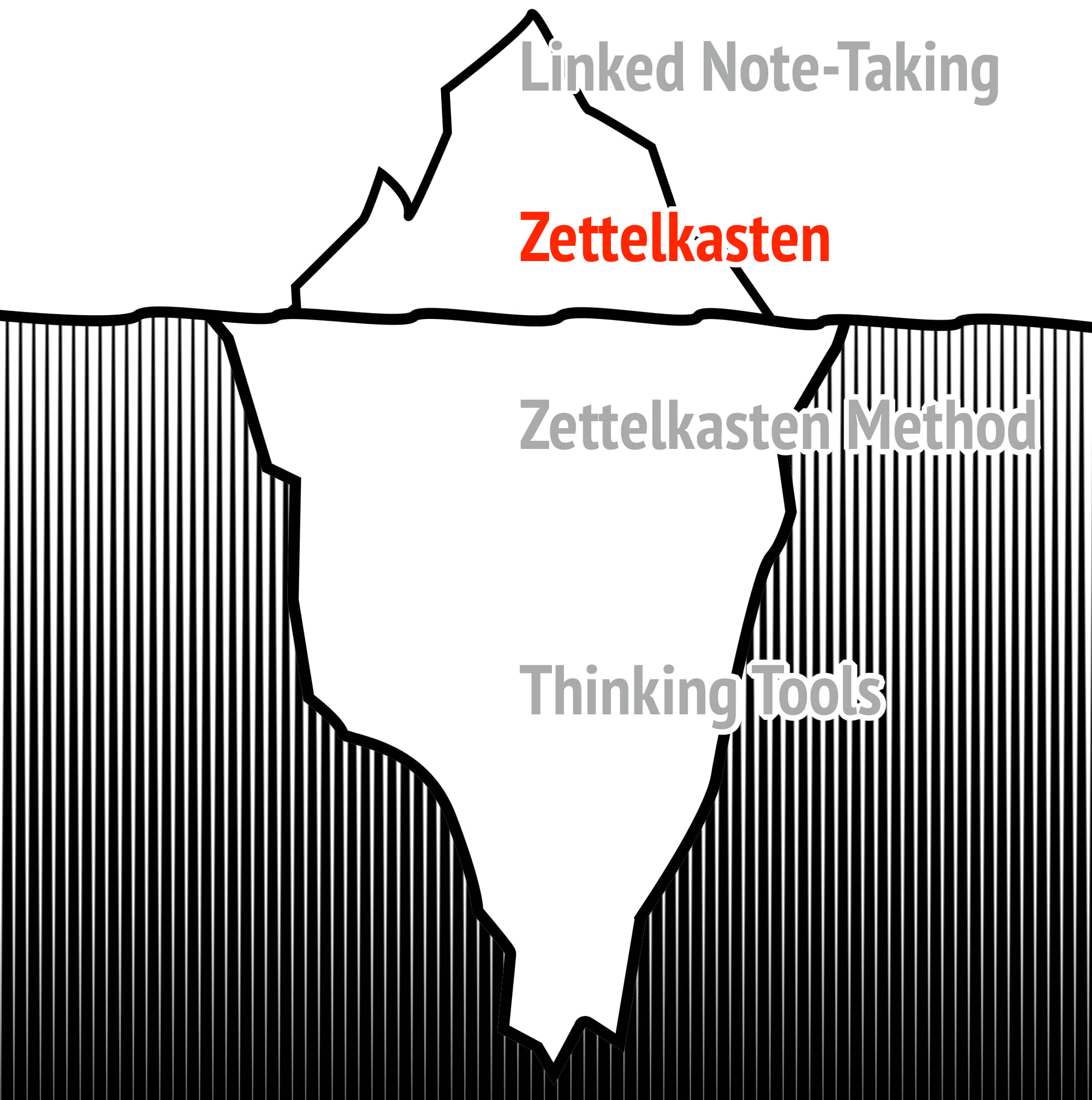

Is this level of processing and interacting with knowledge necessary for the Zettelkasten Method to work? Absolutely not! I’d like to refer you to the Zettelkasten Iceberg:

Work your way down from the top of the iceberg to the depths.

Let’s finish with me giving you the scope of this project. To integrate the points made. Without seeing the whole, you might wonder why I put so much work and effort into getting this one part right.

Our Vision for Zettelkasten.de as a Platform: Atomic Notes are just the beginning

The Zettelkasten Iceberg is more than just a visual representation to illustrate the scope of the entire Zettelkasten Method. It is a map that can help guide your journey in becoming a vicious thinker.

First, you get in touch with linked note-taking. Then you learn about Zettelkastens. If you start to use your Zettelkasten, you will be confronted with problems that you can’t deal with by merely applying simple techniques. Your Zettelkasten is growing and will engage you with issues of time (Creating a note that aims to be useful in 20 years) or complexity (Finding connections within thousands of ideas). The Zettelkasten Method provides answers to these issues. Keep in mind that the Zettelkasten Method is one (currently, the only one) answer to universal issues, if you want to create a home for your mind for life.

The next and final step is to engage with thinking tools.

The Zettelkasten Project aims to cover the entirety of the Zettelkasten Iceberg. Currently, I work to finalise the foundational layer. That is the Zettelkasten Method. This is what the method is all about:

The Zettelkasten Method is a system of principles and best practices to transform your note-taking habits into a constant improvement of your thinking and your personal integrated thinking environment.

This is Zettelkasten 101, available as coaching, a course or book (currently in German, working on the translation to English. Updates here).

The next phase will focus on techniques and methods for working with existing knowledge. Tools for working with concepts, arguments, models, and empirical work will be explored. I aim to push the boundaries of knowledge and learning in the field of personal knowledge management and thinking tools as far as possible, contributing my small part to the vast ocean of knowledge.

I have to use thinking tools and work on my skills to use them constantly. Everything that you read on this blog is based on my need to engage with a wide variety of knowledge. You may read a bit on the scope of my work. My personal vision is that I will work on both projects in synergy: Knowledge and Arete.

Equipped with that background knowledge, let’s review this article.

Atomicity is not just a Zettelkasten gimmick. It is a manifestation of universal patterns of good thinking. We started reviewing two different implementations. Here we are on Zettelkasten level.

By engaging with Atomicity as a principle, we are one level deeper, the level of the Zettelkasten Method.

At the greatest depth, we realise that atomicity means that we aim to get to the essence of an idea. Atomicity is a principle that connects all layers:

- Linked Note-taking: It transforms connected notes to connected ideas.

- Zettelkasten: It is one of the driving principles that makes the Zettelkasten Method unique.

- Zettelkasten Method: As a principle, it guides our engagement towards universal problems of knowledge work.

- Thinking Tools: It is one of the core principles of sound thinking, getting to the essence of individual ideas.

In this article, I covered all the layers. I tried to convey the depth of the topic. And I’d like to address a point of critique of Cal Newport. He is one of the many who state that the Zettelkasten Method is an overcomplication of what can be super simple. I counter this critique with this: The Zettelkasten Method breaks down the strain and complexity of universal principles of thinking and makes it actionable. In fact, the Zettelkasten Method is about simplifying complexity.

One of the typical questions of a Zettelkasten Method beginner is when to break up a note.

There is no methodological orthodoxy that prescribes the right action. Instead, the methodological decisions, like when to break up a note, are downstream decisions of the knowledge work you perform on the respective idea(s). It is not the method that is driving the decisions, but the knowledge work itself. The Zettelkasten Method is just the current best method to create a coherent framework and deal with complexity.

If you are a beginner reading this, try your best and always move forward. You are learning to break down ideas to their essence. This is hard, and the strain you are feeling is absolutely normal and absolutely worth it.

Happy Atomic Day!

-

The original states: “Bei dieser Technik ist es weniger wichtig, wo eine neue Notiz eingeordnet wird.” The direct translation is: “With this technique, it is less important where you place a new note.” In German, there’s often a paradoxical way of phrasing in which you soften the strength of your statement but intend to make a firm point. It’s neither humility nor a deliberate softening. Instead, it’s a layer of typical German politeness, which is especially refined in Swiss German. ↩

-

Equipped with the late Wittgenstein, you will notice that I engaged in the very private language game that I criticise. ↩

-

For you, who are interested in this particular idea: It is an allusion to Daoism. ↩

-

Creation here is meant in a particular way. Please watch Hayao Miyasaki’s critique of a “creation” to engage with this concept. ↩

-

This is about my flavour, since this is not true for the Zettelkasten Method in general. ↩