The Friction Fallacy

TL;DR:

- Friction that increases with system size is an existential threat. Any note-taking or knowledge system whose marginal cost per note rises as the system grows will eventually become unusable, regardless of how beneficial it feels early on.

- A Zettelkasten must be scale-indifferent. It should remain usable even if flooded with massive amounts of low-quality notes. The “one-million bad notes” thought experiment is a stress test for this requirement.

- A system meant to last decades must be robust against change, error, and growth. You will be wrong, your standards will change, your interests will shift, and some notes will become obsolete or bad. The system must tolerate this without demanding global cleanup.

- Friction is not the benefit. Writing in your own words, titling notes, and finding good connections produce benefits like understanding, recall, and idea mastery, but the effort itself is a cost paid to obtain these outcomes.

- Calling effort “beneficial friction” confuses means and ends. Difficulty can be a mechanism or a deterrent, but it is never the value itself. Rebranding effort as virtue commits the friction fallacy.

- There are multiple kinds of friction, and conflating them causes confusion. Friction can be: a bad system characteristic, a costly deterrent, or a mechanism that enables an outcome. None of these makes friction inherently good.

- Most good practices are not enforced by the system. Even analog Zettelkasten setups have very few true forcing functions. Quality depends largely on user engagement, not on structural constraints.

- All decisions about friction must be comparative. The relevant question is never “Does this practice have benefits?” but “Is this the best use of my limited time and attention compared to alternatives?”

- Folgezettel and structure-note-first workflows trade simplicity for long-term cost. Folgezettel provides a clear integration path but becomes rigid and costly as complexity grows. Structure notes are more flexible, refactorable, and resilient over time.

- Rigid structures discourage refactoring, which raises long-term costs. Systems that resist editing force users to accumulate compensatory complexity (links, extra notes, overlays), increasing friction as problems become harder.

What is it about friction? Is it beneficial or problematic? I will address this question on two aspects:

- The problem of friction increases with the system’s growth.

- The problem of rebranding friction as something positive.

The goal of this article is not to come to a definitive conclusion, but something more fundamental. I aim to show how to think about the topic holistically.

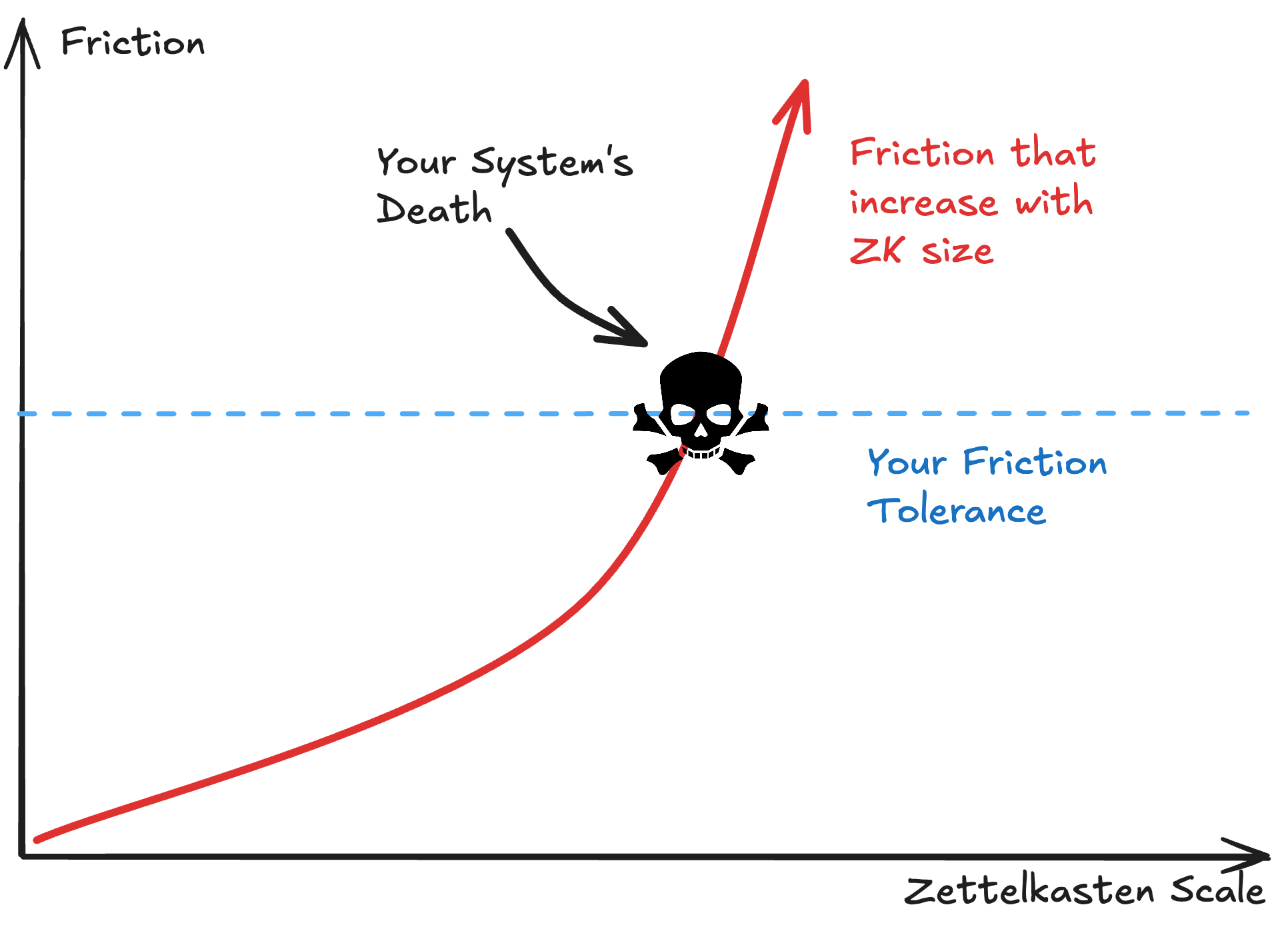

This Friction Will Kill Your System

Building a life-long home for your mind, a Zettelkasten, means that you need to take care of the problem of scale. If you build a Zettelkasten, the goal is to expand the value of past notes well into the future: We no longer take notes just because of our short-term goals, but extend our gaze well into the future. Whatever we are building now needs to be manageable in 20 years.

So whenever friction increases as the system grows, we play a losing game. Sooner or later, we will reach the point where using the system becomes too burdensome to continue, unless we get stuck committing the sunk cost fallacy.

The problem becomes even more pressing when we become dependent on our system. According to this interview, Luhmann barely entered new notes since the early 90s. He didn’t relabel the necessary work (and work ethic!) as beneficial friction. He straight-up said that such a system is hard work. I think Luhmann stopped using his Zettelkasten because he pushed it to the point of failure. This reflects my own experience with the Luhmann-style Folgezettel system. I used it both in an analog and digital Zettelkasten for roughly 2 years. The more you use it, the more complicated it becomes.

Rising friction cost could be labeled as anti-Zettelkasten. The promise of a Zettelkasten rests on the premise that with increasing size, its positive effects increase, too. Any rising friction costs are an existential threat to this promise.

A simple test of scale is the following thought experiment:

What would happen if a demon threw 1,000,000 bad notes into your Zettelkasten all at once?

The first intuition would be that it would render your Zettelkasten useless. But if you had a structure-note-first Zettelkasten, you wouldn’t notice much. It is designed to be indifferent to the size of the Zettelkasten. It has to be. Some characteristics would change. You can’t use full-text search that efficiently. If the notes contain tags, using tags would be less effective. But since you work locally to achieve all the positive benefits of the Zettelkasten Method, you can just keep on trodding.

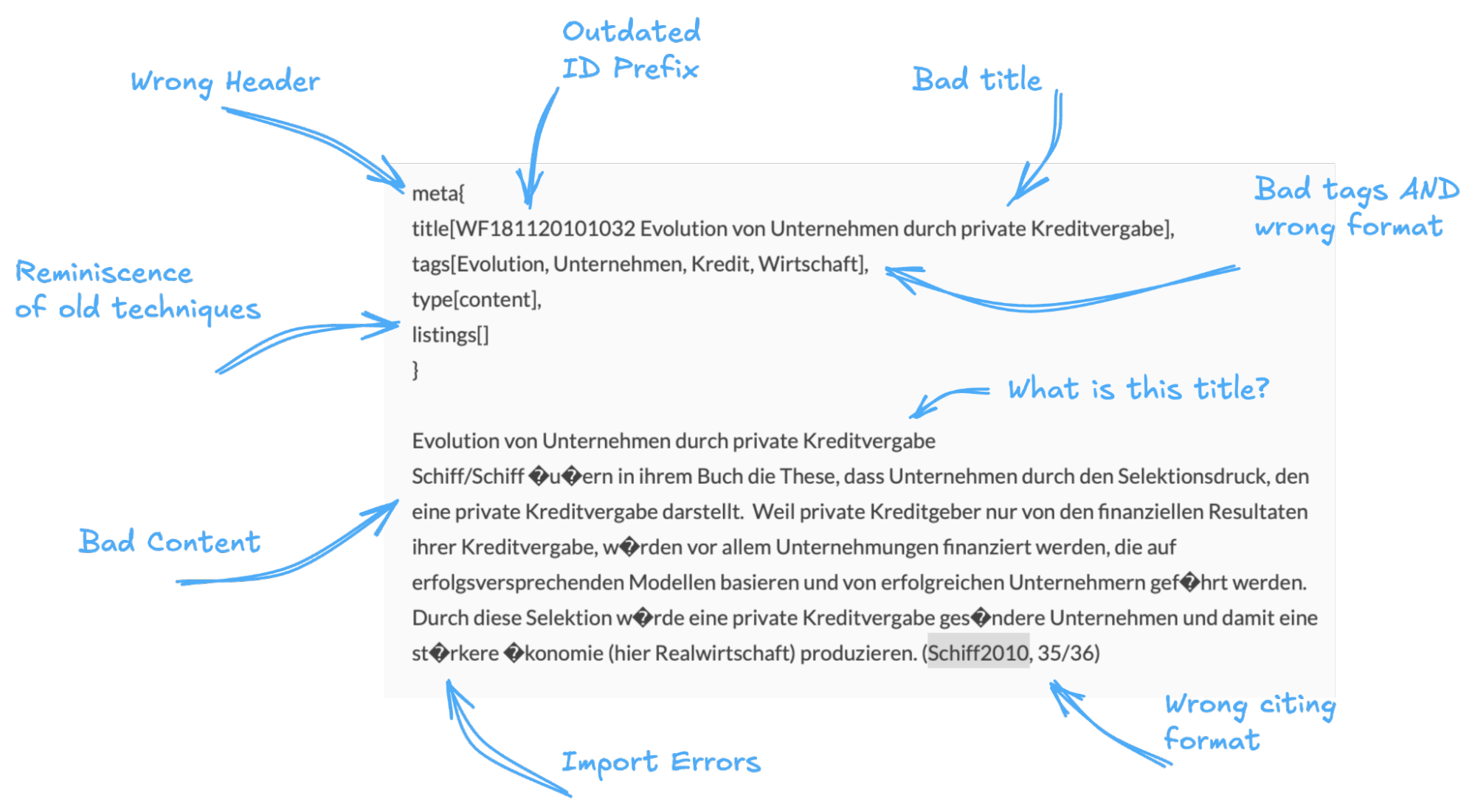

This experiment may sound ludicrous. But while I may not have demon-created notes in my Zettelkasten, I do have thousands of notes that are not up to my standards; many are even bad, and some don’t even follow my current formal standards.

This abomination is still in my Zettelkasten:

My Zettelkasten work is completely unaffected by such notes. When I had to use this note, I’d edit the note, so it is up to my current standards. But I don’t, so I just let this rotten note cadaver be.

The thought experiment, the note-dumping demon, is just a logical conclusion of a problem of the Zettelkasten:

- You will be wrong, sometimes for years.

- You will change the way you work.

- You will grow as a thinker.

- You will work on topics that don’t need tight interaction with each other.

The Zettelkasten needs to be antifragile against complexity. The more complex it grows, the better it should work. To be antifragile, it needs to be robust against scale.

This is the basic motivation behind my tagging method. It mitigates the problem of tagging: the more you use a tag, the less it helps you organise your Zettelkasten. If I’d create tags just by association, I’d have thousands of notes tagged with “diet”. Now imagine clicking the tag and getting a list of thousands of notes. A list of thousands of notes doesn’t give me any meaningful access to content. Object tags, the type of tag that I am using, reduce the number of tags and create a consistent relationship between the note and the tag. This enables specific features that actually help with using the Zettelkasten. However, even object tags don’t scale to infinity. They, too, impose a rising frictional cost on their use. Assigning them is robust against scale. But the resulting tag lists may grow to a dysfunctional size. Based on my experience, the size required to reach the breaking points of these tags is not achievable in my lifetime. So I cheated myself out of my rule of never engaging in a losing game. I may lose the game of tagging, but not in my lifetime. And tags are not critical to me. If you’d delete all my tags, I would shed a tear or two, but not a third. Good enough for me.

This is the point I was making above: Any workflow whose marginal cost per note increases with system size is structurally unstable over long time horizons. Now, let’s dive a little bit deeper into the idea of friction in general.

The Friction Fallacy

The friction fallacy is the belief that friction in the system creates a beneficial effect; therefore, the costs of this friction are worth it.

The idea to relabel friction as something beneficial is not new. Ideas like putting your phone in your backpack instead of your pocket, not buying bad food, and marriage utilise added friction to achieve a beneficial outcome. But it is always about the beneficial outcome, not about the friction. The added work to take your phone from your backpack, the added work to drive to the grocery store to buy the bad food, and the financial and emotional costs of divorce, compared to a simple breakup, are not the benefits you are after. The added friction is a costly deterrent. Here, friction is a beneficial evil.

Another way of thinking about friction is its role in designing an efficient system. Efficiency is measured as the work needed to achieve a particular outcome. Friction increases the work required to achieve a specific outcome. If you want to design an efficient system, friction is your enemy. Here, friction is just bad.

There is a third way of thinking about friction. Friction is how you break your car, it is how you deposit the graphite from your pencil on your paper while writing, and it helps close doors without slamming. You can also generate heat with it, transforming kinetic energy to thermal energy. Here, friction is the very mechanism of achieving the desired outcome.

At this point, we have categories:

- The beneficial outcomes.

- Friction as a bad system characteristic.

- Friction as a beneficial evil.

- Friction as the very mechanism to achieve the beneficial outcome.

This inventory will provide us with a framework to think about friction.

u/TheSinologist on Reddit pushed back on me claiming that friction is a problem for the system:

I was with you until the last sentence, as I find many kinds of friction to be benefits of the system, especially in analog form. Maybe we’re talking about two different notions of friction, but I’m talking about system characteristics that slow you down and keep your brain engaged from one step to the next: writing source notes in your own words and in complete sentences, the spatial limitation of the card, giving main notes titles, finding the right card to follow with your new main card (for me this often involves going through keywords and following them to various cards that could be candidates for the “parent” card, thus reviewing trains of thought and connections). I have pitched Zettelkasten to my composition students, emphasizing the efficiencies of such “beneficial friction.”

This is what I was able to extract:

| Friction Points |

|---|

| Keep your brain engaged |

| Writing notes in your own words |

| Writing notes in complete sentences |

| Spatial limitation of the card |

| Giving notes titles |

| Finding the right card to append your new entry to |

| Reviewing (old) trains of thought and connections |

Of these friction points, two are forces created by the system’s design, while the rest are self-imposed rules. The Zettelkasten doesn’t force you to write notes in your own words. However, you can’t ignore the limitations of the card size or the need to find the right parent card to enter a note.

The spatial limitations of the individual card are not a forcing function but a strong nudge. Luhmann himself often ignored the spatial limitations of a card and let his writing flow onto the next card.1

The need to find a parent note to properly integrate a card, however, is a true forcing function. Technically, you could add each card without ever branching from an existing card. But this would mean not to engage with the system at all. So, we’ll let it count.

The first observation is that even in an analog Zettelkasten, there are few elements of forcing functions. The majority of the good practices are skippable.

Let’s beef up the table by pairing the points of friction with a (not all!) benefit that you gain from engaging with it:

| Friction Points | Benefits |

|---|---|

| Writing notes in your own words | Idea mastery |

| Writing notes in complete sentences | Better notes for writing |

| Spatial limitation of the card | Avoid wasteful wording |

| Giving notes titles | Better understanding through meta-cognition |

| Finding the right card to append your new entry to | Familiarity with your Zettelkasten |

| Reviewing (old) trains of thought and connections | Better recall |

The second observation is that no point of friction is a benefit in itself. All are means to an end.

The third inquiry is whether one can perform the activities mentioned above half-heartedly, so that the resulting benefit does not arise. I think it is self-evident:

| Friction Points | How to Fail |

|---|---|

| Writing notes in your own words | Shuffling around grammar and synonyms |

| Writing notes in complete sentences | Be sloppy |

| Spatial limitation of the card | Note ideas fragmentarily. |

| Giving notes titles | Be vague |

| Finding the right card to append your new entry to | Superficial association |

| Reviewing (old) trains of thought and connections | Careless skimming |

Each element depends on your engagement to be properly respected. The Zettelkasten version that forces you the most to adhere to certain practices is the analog Zettelkasten. Even this Zettelkasten version doesn’t shape your work ethic.

I know this firsthand: I ruined part of my own analog Zettelkasten by just going through the motions. I also ruined part of my digital Zettelkasten. I showed you one example of the slop I produced myself.

The third observation is that the system doesn’t protect you from yourself.

But let’s put aside these three observations and ask ourselves if these practices are beneficial if we engage with them diligently. It should be a hell-yeah, shouldn’t it? But this excitement would be premature.

Relational Reasoning About Friction

All actions have costs. The question is not whether our investment of time, effort, and attention is producing a benefit. The question is whether we are more productive than other resource distributions. Merely establishing a beneficial cause-and-effect relationship between our actions, like carefully titling a note or building a Folgezettel note organisation, is not sound reasoning. It is the equivalent of stating that eating broccoli provides us with protein; therefore, you should eat broccoli for protein. The quality of broccoli as a protein source needs to be evaluated by comparing its performance to other protein sources. The same is true for each element of our Zettelkasten and our engagement with it, and the benefit we try to create.

Let’s focus on a fundamental choice we make when we set up our Zettelkasten.

- Are we faithful to Luhmann and adhere to the Folgezettel technique?

- Or do we put structure notes first?

Both approaches aim for similar effects. They are about avoiding orphan notes and creating some context for the idea you enter. While it is true that both can co-exist, both practices will compete for your attention and the prime position in your workflow.

The Folgezettel structure is, by design, less meaningful and less rich than a structure note. Just comparing the possible structure patterns shows you the difference. While the Folgezettel structure, strictly speaking, only knows one direction of creation (you create children, sibling relationships are accidental, not essential) and three directions of relationship (child, parent, sibling), structure notes are almost limitless. The structuring pattern can be an outline, a table, a drawing, a flow diagram, whatever. Structure notes are much more versatile than Folgezettel for structuring.

The question of what you put first in your workflow, Folgezettel or structure notes, becomes a question of how you fundamentally start to pay attention to an idea when you engage with your Zettelkasten. Will you funnel your ideas through the rigid Folgezettel structure or the hyperflexible structure note apparatus?

Additionally, the Folgezettel structure is crystaline. You grow it and never change it. That means the system strongly discourages editing a single note. If you edit a note, you risk breaking a Folgezettel sequence. You will read that the recommended practice is not to edit the note, but to add a note that contains the idea variation or the contradiction. However, if you work for a long time on a particular topic or problem in this recommended way, especially if it’s a hard nut to crack, you would end up with a very messy Folgezettel structure. Trains of thought will be scattered across your Zettelkasten. You will have to compensate for the inflexibility with direct links and structure notes. In short, the more complex the challenge is, the more cost Folgezettel creates.

With a structure-note-first approach, you will just refactor your notes. Refactoring means restructuring your notes with minimal changes to the content to improve their functionality. See My Demonstration of Atomic Note-Taking for note refactoring as an integral part of processing a source, and Nicole van der Hoeven’s video on note refactoring. It is a much more dynamic and flexible way of working.

I don’t want to dive too deeply into the differences between a Folgezettel-first and a structure-note-first workflow. The point is that you have to pay a price for each. Folgezettel provides a straightforward workflow for integrating a new note into your Zettelkasten. For some, this workflow is easier to start with. At least, you have one structure that you built. The structure-note-first workflow can be a little bit harder to get. The structure-note-first workflow makes it much easier to refactor your notes, giving you much more flexibility to adapt the old structure to your current level.

Both introduce the idea of thinking link-first. You enter a note by finding a good-enough parent connection for your new note as a child (Folgezettel), or you find a structure that can absorb the new idea (structure-note-first). Both approaches still allow you to avoid the hard work needed to create value.

The accusation of committing this fallacy lies at the very heart of Cal Newport’s criticisms of systems like the Zettelkasten Method. They state that the costs of an elaborate system are too high compared to a simpler system. The Zettelkasten will compete for your time and energy with more productive activities. He doesn’t argue that Zettelkasten produces no benefits. He argues that the return on investment is poor compared to simpler alternatives. This critique has to be taken seriously!

Design Laws for Scalable Knowledge Systems

I thought of giving you a sneak peek at an upcoming work of mine. There is much more foundational theory behind each design decision. The difference between principles and implementations took heavy inspiration from Putnam’s concept of multiple realizability. Coherentism influenced my decision to reject Folgezettel in favor of direct linking to map trains of thought. However, I don’t think a 15k-word article on the analytical plausibility of purifying the menu of linking mechanisms is of sufficient public interest.

But I am working on the next layer of the art of knowledge craftsmanship. The upcoming English translation of the Zettelkasten Method book is not just a straight translation but an edition in its own right. The book and the course will provide you with a system, an integrated thinking environment, as a platform. But the more I coach people with diverse backgrounds, helping with chemical engineering, stock investing, academic research, psychotherapy, fantasy RPG, training science, and much more, I feel that I slowly have a grasp on how to provide general tools for working with knowledge.

I will split the upcoming work into an easy-to-apply branch and foundational analytics for people who want to take a very deep dive into the mechanics of knowledge work. I may never have time to publish the theoretical half. So, I’d like to get some of it out. Here are some design laws for knowledge systems that may spark inspiration for you.

Scale-Indifferent Cost. A knowledge system must not increase the marginal cost of adding, finding, or revising information as the system grows. Any workflow whose friction rises with scale is guaranteed to fail over long time horizons.

Locality of Operation. All essential operations, adding, linking, structuring, and revising, must work on the local context alone. Systems that require global awareness, exhaustive tagging, or system-wide coherence do not scale.

Robustness to Bad Input. A viable knowledge system must remain usable even when large volumes of low-quality, outdated, or incorrect notes are added. Quality control cannot rely on preventing bad input.

Tolerance for Change. The system must assume that beliefs, standards, interests, and classifications will change. Any design that resists refactoring accumulates long-term cost.

Friction is a Cost, Not a Value. Friction is never a benefit. Effort may enable outcomes such as understanding or retention, but the effort itself is always a cost paid to achieve those outcomes.

The Means–Ends Separation. Design decisions must distinguish mechanisms from outcomes. Treating difficulty, effort, or inconvenience as inherently valuable confuses means with ends and leads to suboptimal systems.

Engagement Is Non-Delegable. Attention, judgment, and care cannot be offloaded to structure or tooling. Systems that promise protection from disengagement are making false claims.

Comparative Evaluation Principle. A practice is justified only relative to alternatives. The correct question is not whether a method produces benefits, but whether it produces more benefit per unit of time and attention than competing approaches.

Refactorability Over Rigidity. Structures must be easy to revise without cascading changes. Systems that discourage refactoring accumulate compensatory complexity and rising friction.

What’s the verdict then?

The friction fallacy is seductive because it hijacks the confusion and haste we feel in modern times. We are lost and overwhelmed. Trends like slow food or the insane view stats on Kulning are reactions to a strange, nameless monster slipping its tentacles into our minds. Social Media, smartphones, loss of contact with nature, just seeing square angles and grey, dead buildings, not being in touch with our bodies, eating on the go, coffee-to-go, and the breakdown of community, everything is connected.

There is nothing wrong with putting limits on the digitalization of your life by going analog with your Zettelkasten. I am balancing my life with similar measures, like not carrying any capturing device on my dog walks and not reading ebooks.

This article is not about declaring friction good or bad. It’s about recognizing what friction is and thinking clearly about what it does. When we call something “beneficial friction,” we need to ask: beneficial compared to what? Beneficial for whom? Beneficial under what conditions?

The framework I’ve laid out gives you tools to think through these questions yourself:

First, distinguish the categories.

- A bad system characteristic that needs removal?

- A costly deterrent that prevents unwanted behavior?

- The mechanism that produces a desired outcome?

- Or have they confused the mechanism with the outcome itself?

Most debates about friction collapse because people argue across categories without realizing it.

Second, separate means from ends. Once you’ve made this separation, you can ask whether the mechanism you’re using is the most efficient way to achieve the outcome you want.

Third, think comparatively. You have limited time and attention. Every hour you spend titling notes carefully is an hour not spent reading, thinking, writing, or living. The question is never “Does this help?” The question is always “Is this the best use of my resources?”

But I can give you a warning: Watch for rising costs.

If your workflow becomes harder as your system grows, you are in trouble. It might not feel like trouble at 50 notes, or even 500. But at 5,000? At 50,000? If the marginal cost per note is rising, you are playing a losing game. The math is unforgiving.

This is why the demon test matters. If a million bad notes would break your system, then a thousand bad notes will degrade it. And you will create bad notes. You will be wrong. You will be lazy. You will change your mind. Your system must tolerate this.

What the right system can do is stay out of your way when you’re ready to work and provide leverage when you need it. It can remain usable as you grow and change. It can tolerate your mistakes without demanding global cleanup. It can make refactoring easy instead of terrifying.

-

For some examples: https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3a1_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d8ce8_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d8d_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d8d1_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d8d3_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d8f3_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d8f8_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d7g_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d7h_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d7i_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d7i2_V https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_21-3d7j_V ↩