Posts tagged “archive”

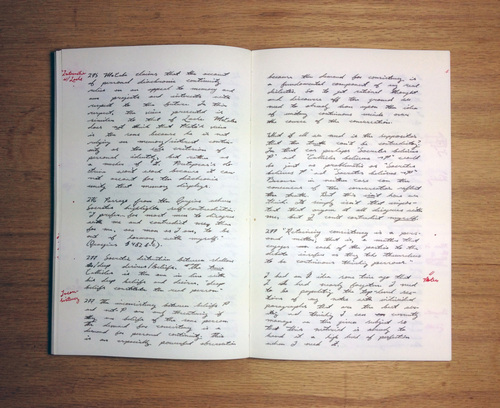

Improved Translation of “Communications with Zettelkastens”

Disclaimer: The original article by Luhmann is charged with his unique concepts that he developed for his social systems theory and a laconic German that is typical to the north of Germany. This is a strange challenge for any translator since you want to be faithful to the original, but at the same time there is a need similar to transposition in music: Transposition means that you lift everything up a pitch. I’d like to show you a translation of a paragraph that highlights the issue of translation itself:

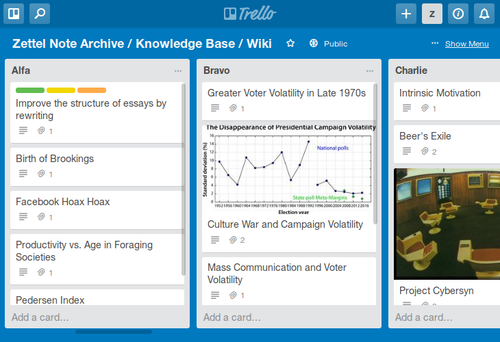

Using Trello as a Zettel Note Archive

If you paid attention to the comments feed of the past couple of months, you will know Nick already. He’s tinkering with interesting plain text stuff – I won’t spoil anything right now; I hope Nick will some day show us the power of plumber, instead. Then just like that he tried out Trello as a Zettelkasten note archive and wrote this amazingly detailed review, including animated GIFs and a sample Trello board to demonstrate what the Trello software can do. This is probably the most detailed post on the entire blog, with more than 50 links and 15 images!

Zettelkasten Live Ep. 2: Limits of our Zettelkasten Archives

In this episode, we respond to Peter’s question: What do we not put into our archives? Here are a few links for stuff we discussed in the video. Christian’s inspiration for note meta-categories back in the day made him include diary entries. Now they’re out.

The Money Is in the Hubs: Johannes Schmidt on Luhmann’s Zettelkasten

Johannes Schmidt gave an awesome lecture but most of you don’t understand German. So I thought I’d give you a quick flash of my notes of some points that I found most important. Keep in mind that this is not a comprehensive overview. Some points are left out or presented with the intention to be more relevant but as a result can be biased.

Nassim Taleb would love the Zettelkasten Method

In my opinion, Nassim Taleb’s most important idea is the concept of Antifragility. Here is his three-concept-model: Fragile means that something doesn’t like volatility and variability. In short: It doesn’t like to be touched. If you send something fragile via mail you write fragile on it so to say: Do as little as possible with it.

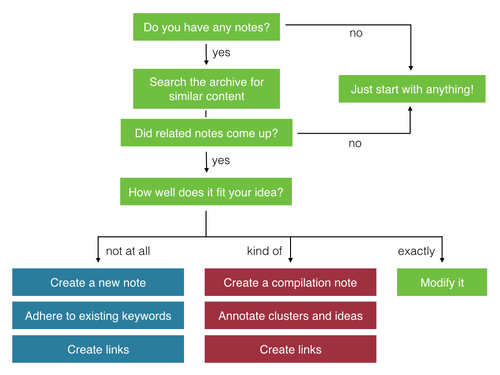

When Should You Start a New Note?

Say you start with a fresh Zettelkasten or you learn more about an existing topic. You write your note and expand the text – and then you ask yourself this: should I create a new Zettel? Should I split this up? Can I attach this detail there? Finding an answer is pretty easy as the scenarios are limited:

Your First Note – Don't Overthink It

The Zettelkasten note archive is the storage of your knowledge. The Zettelkasten Method is an ideation tool, though. Using your Zettelkasten should help remember stuff and spark new ideas which will be stored as Zettel notes again. This process is fruitful and potentially never-ending. All that sounds nice, but naturally you have to start somewhere. How do you start working with your Zettelkasten? What’s the best first note?

Why Luhmann Had to Start a Second Zettelkasten

If you are familiar with the latest research on Luhmann’s original Zettelkasten you already know that his first Zettelkasten is not lost. That’s right: he had two archives over the years. Somehow, a rumor did arise that he lost his first Zettelkasten. It was said that he had to start a new one because of that.

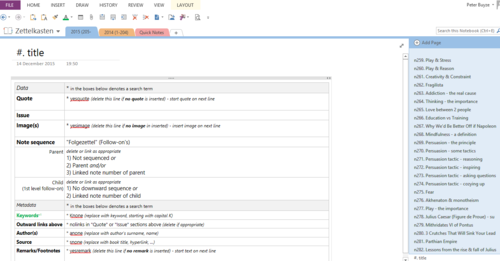

OneNote Review

Today DutchPete, one of the most avid commenters on this blog, will help us fill the gap in software reviews for Windows by talking about OneNote as a Zettelkasten note archive. OneNote is part of the Microsoft Office family and thus available for a lot of different platforms, too, so this is not strictly speaking a PC-centered review. Now let’s see which conventions and techniques make DutchPete productive.

Different Kinds of Ties Between Notes

After the awesome discussion of Sascha’s latest blog post, I meditated about all the different kinds of ties between notes. Here’s what I came up with. When you work with paper, it’s obvious that they have an order – but even digital note archives will put all your notes in some kind of order in the user interface to present them. This is done most likely as a list.

Daniel's Follow-Up About Folgezettel

In response to Sascha’s post about Folgezettel, Daniel published a reaction which was intended to clarify some misunderstandings. Turns out that even after that post and 52 comments, it’s not quite clear where all of us seem to disagree.

Sascha is pointing out that both Folgezettel and hyperlinks adhere to the principle of connectivity, and that a Folgezettel can be realized with links, and is not even something differerent on its own. That’s where Daniel disagrees. But he goes even further and claims that Folgezettel is more fundamental than links are.

If you have something to say, write a blog post and tell us about it so we can link to it in this discussion.

Why You Should Set Links Manually and Not Rely on Search Alone

In the age of lightning fast full-text search, what are links in the archive of your notes good for? In short, search queries are deterministic means to get to Zettel notes: they produce the same results every time. Links are hand-picked references. The idea that makes you create a link is unique, and so is the resulting link. It’s much more personal and thus better suited to help you think.

4 Use Cases to Determine What a Zettel Should Be

Let’s go really basic: What is a Zettel? A Zettel is a note that is part of the archive of your Zettelkasten. You create it to contain knowledge for later use. The answer to “How do I compose a Zettel?” is simple: You form a Zettel in a manner that allows you the most efficient use even if another person would have to use it.

From Reading to Zettel Notes: Dan Sheffler's Workflow for a Doctoral Thesis in Philosophy

Welcome to the bright side of blogging: being part of a discourse!

Dan took some time to write about his workflow, how to get from reading to Zettel notes. (I posted about his setup earlier this week.)

I think the main takeaways of his post are the following and remind us of the foundational principles of bullet-proof knowledge management:

- Separate capturing notes from feeding your long-term archive.

- Take notes immediately: when you have a thought, capture it, no matter how. Do it in your own words.

- While processing your notes, focus on the principle of atomicity. Capture a single idea per note.

- Connect notes heavily.

Dan’s screenshots of Zettel notes in Sublime Text about his doctoral thesis in philosophy convey how you can tackle complex problems in the long term.

About a third of his example seems to be made up of annotated connections to other notes. As you can see in the “mini map” of his note in the upper right, his Zettel is quite long. That’s just fine.

Most of our recommendations sound like you should avoid anything longer than a paragraph. But brevity is quite ambiguous a term. I can imagine Dan is keeping it brief but the material is so vast he’s just adding more and more valuable references and connections to the note.

Writing a doctoral thesis often requires you go deep, and going deep will inevitably result in more details and more references to back up your argument and interpretation. Don’t chop off half of it only because you don’t like scrolling.

Make sure to check out the comment thread where Dan’s post originated.

Keeping a Study Log and Extracting Zettel Notes From It

Dan Sheffler, who you might know for his valuable comments on this site already, has an interesting workflow: first, he captures ideas in a study log while reading; then, he picks the gems and writes Zettel notes later. This difference of “engagement notes” and “memory notes”, as he calls it, fits the Zettelkasten method well.

Should You Have One Zettelkasten or Many?

When you start with a Zettelkasten, you may feel hindered by the plethora of options. Paper or computer? Which application should I choose? Which categories should I create? (Hint: none) How many archives do I need for my projects? The short answer for the last question is: one.

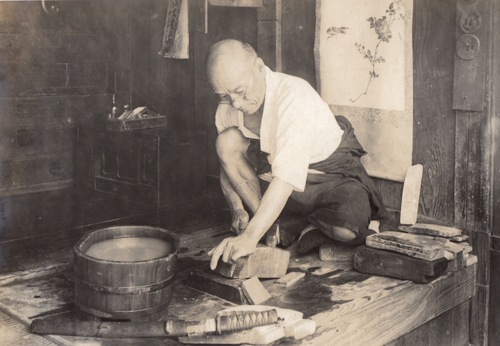

Dominique Renauld on Fond Memories of Working on Paper

Dominique Renauld remembers when he was a student and worked exclusively with paper notes. He was fond of Roland Barthes1 and grew even fonder of Arno Schmidt – both avid Zettelkasten users.

Nowadays, Dominique uses Tinderbox for anything. Check out the slides and video of his post to see what working with Tinderbox can look like.

We can learn to be playful with our items of knowledge. We only have to think about what we would do if the knowledge was organized on paper. Tinderbox is a great application to work visually, although I haven’t tested it seriously, yet. If your app doesn’t support any visualization, simply start to draw diagrams. With a playful attitude, you could re-phrase existing notes, read and think about them, then write down your thoughts again.

It doesn’t suffice to feed new stuff your Zettelkasten. You have to attend to its needs, too. The result will be stronger cross-connections.

-

When Barthes lost his mother, he took notes about the process of his grief. The collected fragments were published as a book. I always rejoice when an author uses “Zettelkasten” colloquially, which isn’t too uncommon in German; and then I wonder why no one at university takes this method seriously. (The German source says: “Tatsächlich könnte man das Buch viel eher als einen geordneten Zettelkasten oder eine pedantisch geführte Materialsammlung bezeichnen. Tag für Tag wurde dieses Archiv der Trauer um neue Notizen erweitert, deren Kürze und Komposition oftmals an die von Barthes geliebten japanischen Haikus erinnert.”) ↩

On Using Intratextual Tags

Some of you guys asked for more practical articles about the Zettelkasten Method. So here we go. I use two different tags: some are in the header and some are right in the text body. Here is an example Zettel about the problematic implications of a materialistic view on the human mind.

Why Categories for Your Note Archive are a Bad Idea

A friend of mine recently asked for help with getting started. It was very hard for him to overcome initial uncertainty: how do you know you’re sufficiently prepared to start filling your note archive? Which categories should you prepare before you begin? My answer surprised him and was dead simple: don’t. Don’t prepare. Don’t invent categories. Just let it come.

1Writer — Access Your Zettelkasten On Your iPad and iPhone

My MacBook isn’t going to recover, so I switched to an iPad for mobile writing and development. I found the one and ultimate application to access my Zettelkasten note archive on the go, while also being able to write long-form blog posts or proof-read texts from Sascha. Today I want to give a shout out to an app called 1Writer.

You Don't Need a Wiki – Being Content with Your Software

Manfred has left a comment on his blog about my criteria to review apps a while ago. This made me reflect on the importance of note connections and their role in being a successful learner, whatever that means. Manfred believes I don’t value direct connections or links between notes enough. He got me wrong on this.

Eco's 'How to Write a Thesis' Available in English

Finally, after being in print for 38 years in other languages, How to Write a Thesis by Umberto Eco is now available in English!1

I have mentioned the German translation of Eco’s book in the past already (in “Collector’s Fallacy” and “Making Proper Marks in Books”). From his book did I learn that not all Zettel are created equal. If you worked solely with index cards in the 70s, all this mattered a lot.

Remember that it’s possible to have a Zettelkasten without a computer. If you work on paper, you’ll be slow as heck. But you’ll still be more productive than all the other folks not thinking twice about proper knowledge management. Eco’s workflow details will help tremendously if you don’t know how to work with the tools available.

Nowadays, we have reference manager software, note-taking software, PDF annotation software, and whatnot. We tend to think in terms of our tools. But this veils our understanding of the ideas we work with, the texts we read. If we managed everything with index cards (but in different boxes), it’d be easier to look behind the How and see the What instead. Paper is almost never feature-bloated. Software makes it harder, because you can always get stuck at the surface level, switching apps all the time and looking for the next great feature. (Note the book isn’t called What to Write a Thesis With.)

If you care for non-fiction scholarly writing, if you’re a student, or if you’re just trying to figure out what kinds of Zettel notes there are and where they come from – pick up the book! It’s an educational read, but keep in mind most of the tips are outdated since personal computers exist.

(via Manfred of Taking Note; cover image © 2015 The MIT Press)

-

Affiliate link. You buy from this link, and we get a small kickback from amazon. No additional cost for you. ↩

ConnectedText Review (and Other Multi-Purpose Info-Managers for Windows)

Paul J. Miller wrote an extensive review of ConnectedText you might want to have a look at if you’re running Windows and are still looking for a note-taking application which does more than store notes.

We’ve added Paul’s review to our ConnectedText “tools” entry where you find other resources to get you started.

ConnectedText is hard for me to describe because it can do so many things, provided you set up some templates to get you there. I leave it as a research task to you, the reader, to find out what the app may do for you.

More interestingly, Paul mentioned the other Windows apps he tried in the past. See his MyInfo review (seems to have a great search) and his Ultra Recall review (the Calendar view sounds nice for an all-purpose info manager). If ConnectedText isn’t your thing, maybe one of these is. Keep in mind that all three do more than store notes in an archive. You can manage most of your life with them if you want to, it seems.

Neither Sascha nor I have hands-on experience with any of the three apps. Share what you think with us in the comments!

How to Program Yourself for Productivity and Stop Searching for the Ideal Software

In search for the perfect software application to manage a Zettelkasten note archive, surprisingly, I have become the tool I was looking for. Here’s what you have to do once you settle for the important things and let go of false feature needs. When I dream about the perfect Zettelkasten software, everything revolves around reference awareness:

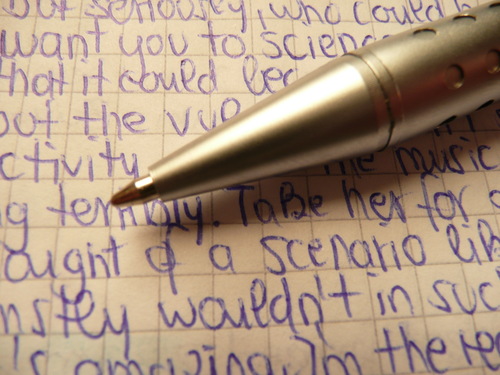

How to Write a Note That You Will Actually Understand

If you not only take notes but also edit them before you put them into you archive (hopefully a Zettelkasten), you will save energy and time, and preserve sanity. It will also enhance the clarity of your writing in general. If you use the Zettelkasten Method you will be faced with your ghosts of the past. If I ask my Zettelkasten about a term like evolution, it throws Zettels from 2010 at me.

The Two Forms of a Zettel

In this post I try to dig into the nature of a Zettel. When philosophers speak about the nature of something they refer to its most basic qualities. If you substract one of those you would have something different. This is a bird’s eye view consideration. I believe that it is useful to take a step back. But you need to consider that the practical applications need some additional steps of reasoning.

How to Write a Book – Without Even Trying (so hard)

In my last post A Life-Long Writing Project on Writing – and My Anxiety I said that I wrote a (small) book on writing while researching it. In this post I’ll present the method which led to this book.

Use a Short Knowledge Cycle to Keep Your Cool

It’s important to manage working time. Managing to-do lists is just one part of the equation to getting things done when it comes to immersive creative work where we need to make progress for a long time to complete the project. To ensure we make steady progress, we need to stay on track and handle interruptions and breaks well. A short Knowledge Cycle will help to get a full slice of work done multiple times a day, from research to writing. This will help staying afloat and not drown in tasks.

Building Blocks of a Zettelkasten

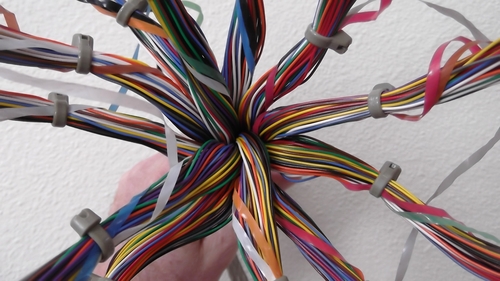

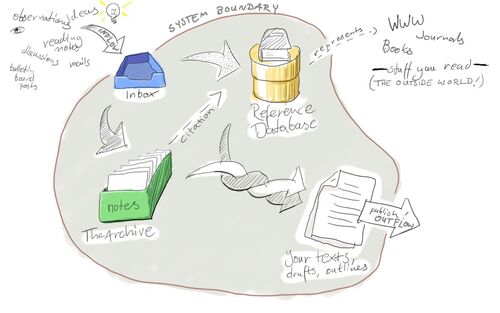

I am working hard on the “Building Blocks” chapter of the Zettelkasten book and I want to finish it first to show it to the public. It covers all parts of the toolkit. To sketch a structure and talk about its components, I need to get the requirements and implementation done before talking about workflow details. Today, I want to show you a birds-eye view of the overarching systems metaphor I’m using in the book.

Reading Habits: Putting It All Together

I am moving next month, and so I though about getting rid of stuff in my life. There are lots of books I’ve read, but from which I never processed all the notes. I know for sure that at I finished least one book in the collection about two years ago! You see, I was, and still am, vulnerable to the Collector’s Fallacy. While I try to get through the pile of books, I reviewed my reading process. This is a summary where I put together some of the topics I already wrote about

You Only Find What You Have Identified

I want to answer the question: Why are unique identifiers useful when you work with a Zettelkasten? The objective of a Zettelkasten note archive is to store notes and allow connections. Both are necessary to extend our mind and memory. As long as the software you use doesn’t provide any means to create links between notes, you have to come up with your own convention. Even if the software did provide such a mechanism, I’d suggest you think twice about relying on it: I want to evade vendor lock-in for my Zettelkasten, and I think you should, too. So let’s assume you don’t care about the software and create your own hyperlink scheme.

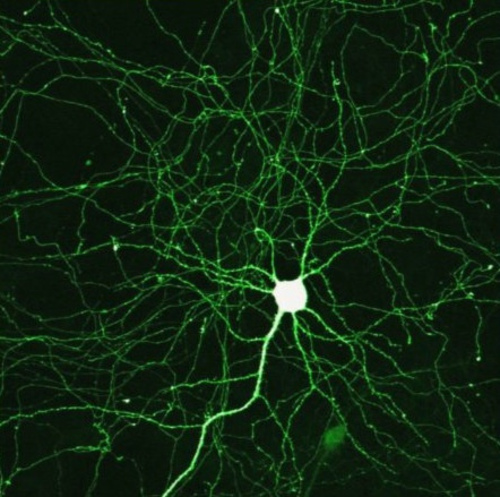

Extend Your Mind and Memory With a Zettelkasten

A Zettelkasten is a device to extend your mind and memory so you can work with texts efficiently and never forget things again. Both permanent storage and interconnectedness are necessary to use the full potential of an archive for your notes. You need a permanent storage for your notes so they can give a cue for the things you want to remember. You also need to manually connect notes to create a web of notes which adjusts to the way your mind works.